Americans may not remember that the United States once forced more than 120,000 Americans to leave their homes and live in isolated internment camps. Yet after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the federal government and the US military did exactly that. They ordered Americans of Japanese descent to move to seven such camps — euphemistically, “Assembly Centers” — spread across four Western states.

A study by a military officer had already concluded that Japanese residents of the US posed no significant security threat. Yet hysteria ran high. The widely respected liberal columnist Walter Lippmann claimed, with no basis, that “the Pacific Coast is in imminent danger of a combined attack from within and from without.” And the rabidly racist Congressman John Rankin, of Mississippi, was explicitly calling for a “race war.” On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed an executive order requiring the removal of all Japanese Americans from the West Coast. (Though America was also at war with Germany, only a few members of the pro-Nazi German American Bund were detained.)

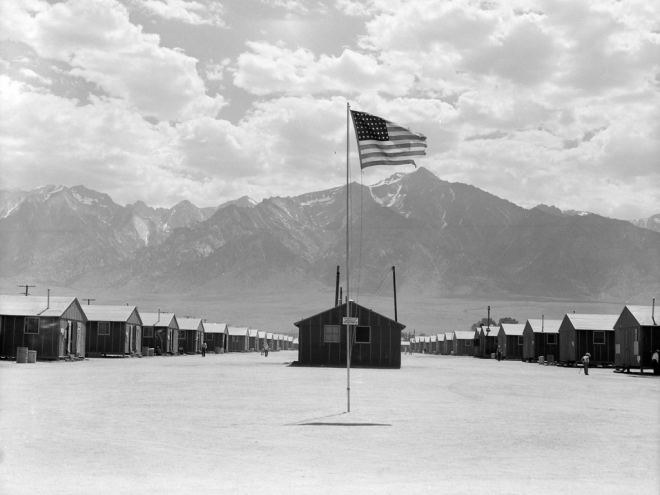

One Jewish woman, Elaine Buchman, chose to accompany her American Japanese husband, Karl Yoneda, and their young son, when they were ordered to leave San Francisco. They were assigned to the internment camp at Manzanar, located in California’s Owens Valley east of Fresno. Some 6,500 Americans were to be sent to Manzanar, including 2,300 children, where they faced crowded conditions, limited privacy, frigid mornings, dust storms, high temperatures of 120 Fahreneit, poor sanitary facilities, obtuse administrators, and armed military police. None had been accused of illegal or subversive activity.

Elaine worked at a factory in the camp which produced camouflage nets, and she was proud to be part of the war effort. So was her husband, who vociferously despised the imperialist Japanese regime. But there was a small, violent group of Japanese internees at Manzanar who hoped that Japan would win the war. Those pro-Axis Japanese despised Karl for his loyalty to the Allies and repeatedly threatened him — harassment which he called “mental torture.” They even threatened Elaine’s and Karl’s son, Tommy. Meanwhile, outside the camp, the War Relocation Authority was deciding who would be permitted to live on the Pacific Coast according to whether “non-Japanese blood exceeds Japanese blood.”

Elaine’s story is told here in vivid detail by the writer Tracy Slater, who herself married a Japanese man. Slater is acutely sensitive to the emotions and motivations of the people she describes, as well as to the larger issues of justice, race, and government accountability. Her account of prejudice, the abuse of power, and the rationalizations used to justify them, is as relevant today as ever. Slater’s natural empathy and sharp observations make this historical account a sensitive, affecting human story as well.

Bob Goldfarb is President Emeritus of Jewish Creativity International.