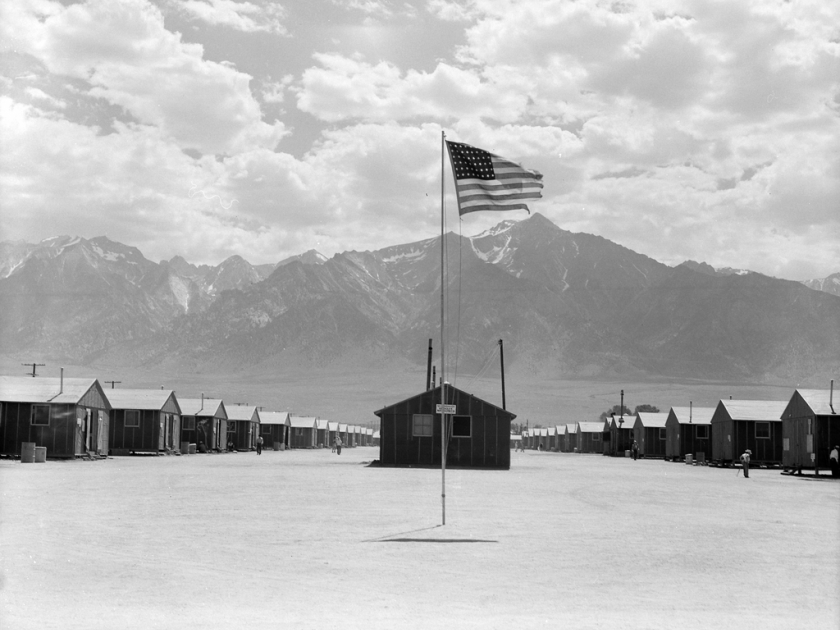

Barracks with Mt. Williamson, by Dorothea Lange. Via Wikimedia Commons

During World War II, while millions of European Jews were imprisoned and ultimately slaughtered by the Nazis, tens of thousands of Japanese Americans were imprisoned by the United States government. Among the incarcerated were over 2,000 members of mixed-race families — including one Jewish woman and her three-year-old son.

Elaine Yoneda, a leader in the prewar West Coast labor rights and anti-fascist movement and the daughter of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, was the wife of Japanese American leftist activist Karl Yoneda. After the Japanese Navy bombed Pearl Harbor, the US government forcibly detained anyone on the West Coast with, in the words of one official, even “one drop of Japanese blood.” Elaine was faced with a devastating choice: to enter a camp near Death Valley named Manzanar with Karl and their son, Tommy, or let them be taken there without her. She did what almost any mother would do. On April 1, 1942, Elaine and Tommy became the only Jewish incarcerees on record in any of America’s World War II concentration camps. But ensuring she could protect her son in Manzanar came at a steep cost for Elaine: she was forced to leave behind her white daughter from a previous marriage.

The Yonedas’ story — and those of their approximately 120,000 fellow prisoners — highlights the profound effect that euphemism can have in shaping a national narrative. Since the end of World War II, Manzanar and the other sites incarcerating Japanese Americans have been almost uniformly referred to as “internment camps.” In the early 1940s, however, they were widely called concentration camps — a far more accurate description.

According to Merriam Webster, a concentration camp is “a place where large numbers of people (such as prisoners of war, political prisoners, refugees, or the members of an ethnic or religious minority) are detained or confined under armed guard.” This is what Manzanar and the American camps like it were. On the other hand, as the history organization Densho explains, “internment” is a legal term for the detainment of foreigners designated as “‘enemy aliens’ in time of war.” Using this term for camps like Manzanar only perpetuates the myth upon which the entire forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans was built: that they were an “enemy race,” in the words of US officials at the time; that regardless of their American citizenship, they were foreigners, eternal outsiders who could never be trusted.

The Nazis used the term “concentration camp” to obscure the truth of their own slave-labor and extermination centers. The Germans first referred to their camps as “special concentration camps.” As the world discovered them, the latter two words stuck. But the Nazi camps were not ultimately concentration camps any more than the camps for Japanese Americans on US soil were internment camps. A look at Elaine and Karl Yoneda’s painful predicament in Manzanar shows how individuals were personally impacted by the use of euphemism. At first, “concentration camp” was a term that the Yonedas accepted and used. But as the war dragged on and news of the Nazis’ own camps began to leak, they became increasingly ambivalent about the term. So did the American media, the public, and in particular the leftist community. The incarceration of the West Coast Japanese American community was “necessary,” argued even the leftist papers. But no conclusive evidence ever existed of Japanese American sabotage, of risk to the nation from this population of American citizens.

Since the end of World War II, Manzanar and the other sites incarcerating Japanese Americans have been almost uniformly referred to as “internment camps.” In the early 1940s, however, they were widely called concentration camps — a far more accurate description.

This truth did little to sway progressives (including those on the Jewish left) like the journalist Walter Lippman. “The Pacific Coast is in imminent danger of a combined attack from within and from without,” he wrote. He admitted that “since the outbreak of the Japanese war there has been no important sabotage.” But, he argued, “This is not, as some have liked to think, a sign that there is nothing to be feared. It is a sign that the blow is well-organized and that it is held back until it can be struck with maximum effect.”

Detained under armed guard, removed from society, the Yonedas found few ways to join the nation’s battle against the Axis. But they longed to participate in political struggle as they prominently had before the war, to maintain some sense of their pre-incarceration identities and some role in their former leftist community, even from behind American barbed wire. They yearned to participate in the struggle against Imperial Japan’s brutal colonization of their Asian neighbors and the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. The only avenue for doing so from Manzanar was to proclaim America’s righteousness by downplaying the obvious civil-rights and Constitutional breaches of its own race-based mass incarceration.

Instead of a concentration camp, Manzanar became the Yonedas’ own “battlefield in helping to win the war,” Elaine wrote in her diary, a symbol of their own “sacrifice” to the war effort. “This project,” as Karl referred to Manzanar in a letter to People’s World, “will take its place in American history – in the fight for the preservation of democracy and the defeat of the Axis-Fascists.” Whether or not Manzanar and the detention centers like it were concentration camps or were “in violation of the Constitution” were questions that would have to wait, “to be addressed after the war.”

Although the Yonedas faced perilous violence in Manzanar, they all survived. Once the army agreed to dispatch Japanese American citizens to battle, Karl became one of first men from the US camps to volunteer to be sent to the Pacific front. After the war, Elaine and Karl fought for redress for the Japanese American community. They joined many camp survivors and descendants in refusing to let our nation forget its illegal detention of 120,000 US residents — the great majority US citizens — with no due process. But the question of whether Manzanar was a concentration camp, especially in light of concurrent Nazi atrocities in places called concentration camps, continued to haunt them until they died.

The horrors of the Holocaust shouldn’t obscure America’s wrongdoings. The US government put Japanese American citizens in concentration camps. Naming this truth remains fundamental to a full and accurate historical record, particularly crucial now amid governmental attempts to scrub past traumas and struggles from the national narrative. Recognizing this history honors families like the Yonedas and the tens of thousands of others incarcerated along with them. Perhaps most importantly, by foregoing euphemism, we recognise our ability to hold multiple truths simultaneously: that of the millions who suffered and perished in Nazi extermination centers, and that of the multitude of US citizens who lost homes and property, endured family separations and agonizing hardships, sometimes died violently, and were wrongly imprisoned simply because of their ethnicity or whom they loved.