Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

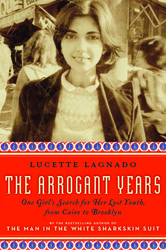

Lucette Lagnado’s most recent book, The Arrogant Years: One Girl’s Search for Her Lost Youth, from Cairo to Brooklyn, is now available. Lucette won the 2008 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature for her memoir The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit: A Jewish Family’s Exodus from Old Cairo to the New World. She will be blogging all week for the Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning’s Visiting Scribe.

I couldn’t seem to escape Egypt this year – though I never set foot outside New York.

I couldn’t seem to escape Egypt this year – though I never set foot outside New York.

For months, I worked fiendishly to finish The Arrogant Years, my memoir which takes place in Cairo and New York. But whenever I’d put the book aside, I would follow news of the revolt unfolding on Tahrir Square. The revolution was addictive – I couldn’t seem to get enough of it. I found myself constantly clicking on online news of Cairo, or tuning in to CNN. It was all so exciting.

And terrifying. Even as I witnessed the euphoria, I felt a strange sense of alienation – I couldn’t feel much joy or passion, couldn’t quite cheer the protestors as the entire rest of the world seemed to be doing.

As I noted in an essay for The Wall Street Journal this weekend, I have been feeling uneasy since the start of the uprisings. Yes, I supported calls for democracy and believed that strongman Hosni Mubarak had far outstayed his welcome. I simply thought that viewing him as the cause of all of Egypt’s woes – even as the military that had ruled the country with an iron hand for 60 years was being embraced as saviors – was bizarre and misguided.

Nine months after the protests began, Mubarak is gone, on trial, and possibly on his way to being executed — but Egypt seems no closer to democracy. Worse still, it has descended into a kind of lawlessness, marked by occasional really scary incidents – attacks on Coptic Christians, the brutal sexual assault of CBS reporter Lara Logan, and, most recently, the storming of the Israel Embassy in Cairo, which forced the departure of the Ambassador and his staff.

All of this has made me terribly sad – and brought back some awful memories to boot. Somehow I have found myself transported to an Egypt I didn’t really know, when I wasn’t even born — the Egypt of that first revolution of 1952, when King Farouk was overthrown, the military took over, and the world as my Egyptian-Jewish parents knew it turned mean and fierce. There was a certain wildness, terror to the period, I was always told. Egypt’s Jewish community, once comprised of 80,000 Jews or more, left in droves until there were only a few Jewish families, including mine, trying to hang on.

We left in 1963 and settled in New York. My parents spoke lovingly of the Egyptians they had left behind, with one exception – the dictator Gamal Abdel Nasser who was charismatic, arrogant and bombastic, and galvanized the public with a rhetoric of hate. The experience taught my family – taught all of Egyptian Jewry, I think – to be watchful and wary of revolutions and all they promise.

Hence my lack of excitement at a time everyone – even my mother-in-law – seemed to be cheering Mubarak’s ouster and the events in Tahrir Square and the promise of it all.

It is rather stunning to me how ineffectual the Egyptians have proven to be at nation-building. They were terrific protesters, the world was riveted by the daily protests and everyone raved about the “Google guy” and the “Facebook revolutionaries.” Yet none of these original leaders with their lofty promises of democracy and their slick use of the Internet has emerged to date to take the country to the next phase. Instead, the ones to watch have been the Muslim Brotherhood, who seem determined – despite their moderate patina – to take Egypt in a different and frightening direction.

This past year I could always find comfort in my book, and the very different Cairo I was conjuring up – my mother’s Cairo, the Cairo of the 1920s and 1930s, when there was genuine political debate and a tolerant society. Egypt was ruled by a monarch, yes, and yet to my mind, looking back, King Fouad seems so much more benign somehow than those military guys who came to power in 1952. The Cairo of my book is particularly striking because of the lovely status Jews enjoyed – in the same period that they faced persecution in Europe, they were rising to the top of this Arab society.

There were even Jewish Pashas, the most prestigious social title that an Egyptian could enjoy.

It seems to have been such a promising society, truly multicultural, where Jews and Moslems and Christians seemed to co-exist with a considerable degree of harmony. What I find myself wondering is why the Egyptians, as they cast about for a model of nation-building – Turkey, Iran, Hamas – don’t simply look back to this halcyon period of their own history?

Lucette Lagnado will be blogging here all week.

Lucette Lagnado (z“l) is the author of The Arrogant Years: One Girl’s Search for Her Lost Youth, from Cairo to Brooklyn and The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit: A Jewish Family’s Exodus from Old Cairo to the New World.