Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

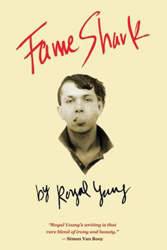

Royal Young’s memoir, Fame Shark, was published last month by Heliotrope Books. Read his Visiting Scribe posts here.

Royal Young: When I started Fame Shark I was still under the spell of this deluded, narcissistic idea that it would catapult me to celebrity. The writing of it was the best therapy, a shock of awakening. In digging into hard truths about my own loneliness and unhappiness I was able to see the shape of myself. Doing hard work as a journalist for The Forward, Interview Magazine and New York Post for seven years, and dealing with poverty and constant rejection forced me to become happy with myself as a person. Celebrity was always a means of escape for me. Yet, wherever you escape to, you take yourself with you. I think being crushed by life, being forced to deal with the underlying issues behind a quest for external gratification is so healthy — and honestly saved my life. It’s something we all come up against. Whether it is fame or success, food or drugs, we all have a craving to get outside our own lives. The trick is to embrace who we are. That is the only true way of getting out of it.

The most important part of being a Jew for me has always been the idea that questioning, constantly challenging and exploring cultural norms is important. I think when we believe we have nothing left to learn, that is when our souls die.

JW: You aptly capture the wildness and almost insanity of the now famed Lower East Side. Do you miss that craziness at all, do you feel that you live, and perhaps the NYC world lives a more subdued life since that time?

RY: I know it is insane to be nostalgic for waving hi to hookers on my way to kindergarten and junkies collapsed in puddles of their own piss, but there it is. I can’t help but miss my youth and the city as it was. There definitely was a wildness, but also beauty to pastel colored murals by Chico, sneakers dangling from streetlights and hydrants blasting jets of endless water into summer streets.

I also yearn for history. My grandparents grew up in the Lower East Side of the 1930’s when it was an Eastern European shtetl transplant. This sense of connectedness to a shared past is gone. All of New York feels like a mall to me now. Every corner is now a Duane Reade, Chase Bank or 7 – 11. I don’t hate it. It’s just boring. New York feels so sanitized now.

JW: When all is said and done, does fame mean anything to you anymore? Do you feel a current affinity for it? Do you think it has any value, at all, this pursuit of fame you so eloquently document?

RY: Not really. It depresses me honestly. Success as an artist is still important to me. Getting my work to a wide audience, sure. And I do think there are so many writers and artists who deserve more exposure than they get. But Fame Shark is in many ways a satire. I think it’s pretty obvious that fame can make people utterly miserable, even suicidal.

Our culture is so obsessed with raising people on pedestals, invading their privacy, exploiting their insecurities. In an America racked by poverty and a world wrecked by climate change I completely understand the escapism of Hollywood. But it is pretty clearly damaging to the humans we promote to demi-god status through tabloid worship and reality television. I crave something deeper.

JW: Perhaps one of the greatest shifts in the publishing world has been the rise of memoirs of trauma and desire as opposed to memoirs of accomplishment — i.e., young people are writing memoirs at the beginning of their lives as opposed to people writing memoirs after they’ve accomplished something. Do you see this as significant?

RY: Absolutely. I think both are equally important in different ways. To look back on and reflect on a life gives incredible perspective. But my hope is that young memoirs of turmoil, cautionary confessions about struggling youth are more helpful to the youth that still struggle. As a frustrated young person, reading the revelations of writers I could relate to helped me understand I wasn’t alone. Fame Shark is a book for any age, but my greatest inspiration is when parents come up to me after a reading and say ” My kid is going through something similar right now and I want to get the book for them. I think it will help my child.”

JW: Instead of asking the classic question about seeing yourself as a Jewish writer, or not, I would rather ask how you see the relationship between your Judaism and your writing, in your life and in your book?

RY: Being a Jew for me is about exploration. It’s about pursuing creativity and being yourself despite persecution, no matter what the odds. Obviously prejudice is mostly — though not completely — removed from my life experience, but coming from an immigrant family, I always identified as an outsider. Being the only Jew amongst my classmates until junior high school reinforced this.

As a writer, I explore what I know, what I was brought up in. That is a culture of fighters, survivors, people who wanted to escape their old-world pasts into an American future that promised brightness, inclusion, but more often brought pain, exclusion, sadness. It’s about pushing past that. Not through religion, but through spirituality and a connection to my roots.

JW: There’s an electric, almost kinetic energy to your fast-paced book, much of which comes from your writing style, but some of which comes from the subject matter of youth chasing fame. How do you, in your writing, and in your life, find a balance between what we might call the relatively boring stability of adulthood and the frenetic and experimental energy of youth?

JW: There’s an electric, almost kinetic energy to your fast-paced book, much of which comes from your writing style, but some of which comes from the subject matter of youth chasing fame. How do you, in your writing, and in your life, find a balance between what we might call the relatively boring stability of adulthood and the frenetic and experimental energy of youth?

RY: Thank you. I’m still figuring that out.

JW: Looking back now, is there any advice you would like for young Royal Young to know?

RY: Patience. All that cliche bullshit that is actually true wisdom: that it is about the journey, not the end. That there is a time for everything. And humility is a huge one. When you’re unhappy with yourself I think you’re so much quicker to trump yourself up, to self-glorify, to be mean. Kindness comes with loving yourself. I hurt myself for so long because I didn’t believe I was worth much more. The hardest thing I’ve ever had to do is admit how lost I was, how much I needed love and time. Let yourself know what you know. The harder I work, the luckier I get.

Joseph Winkler is a freelance writer living in New York City. He writes for Vol. 1 Brooklyn, The Huffington Post, Jewcy, and other sites. While not writing, Joe is getting a Masters in English Literature at City College. To support his extravagant lifestyle, Joe also tutors and unabashedly babysits. Check out his blog at noconversationleftbehind.blogspot.com.