Artist David Kassan discusses his most recent portrait series and exhibition, Facing Survival. Known for his highly realistic life-size paintings, Kassan used this series as a way to artistically portray Holocaust survivors and their stories.

Samantha Baskind: What compelled you to create an entire series of portraits depicting Holocaust survivors?

David Kassan: The series started five years ago when a collector of mine from Israel asked if I could paint his mother-in-law on commission. I had some bad experiences early on in my career when I was commissioned, and since then I try to avoid them like the plague. I told this collector that I appreciated his interest in my work, but I wasn’t taking on commissioned work at the time. He then said that his mother-in-law is a survivor of the Shoah. I was immediately interested in meeting and painting her. Later that week, he asked his mother-in-law about the painting and showed her my work. Unfortunately, she politely declined to be painted.

SB: Why did her status as a survivor change your mind about taking the commission?

DK: At that time, I was into filming my process as well as interviews with my subjects. I love the idea of hearing a subject talk about his or her life and using it to give the painting more context, and I felt that this process would be especially interesting with Holocaust survivors. I also found that I was connecting with my own family history. My paternal grandfather escaped ethnic cleansing in 1917 to come to America from the border of Romania and Ukraine. My father didn’t have a relationship with him and I never got to hear his testimony. I’ve only read it in a book that he wrote, which I just found out about a few years ago.

SB: The USC Fisher Museum of Art is currently exhibiting thirteen of your highly realistic individual portraits of Holocaust survivors, along with one large group painting of eleven Auschwitz survivors. Clearly, your interest was piqued by the commission that fell through. How did you eventually paint a survivor, let alone so many more?

DK: This series started with the purpose of getting to know one survivor and documenting her first-hand account of the Holocaust. Since then, its scope changed to gathering information, filming interviews, and creating paintings as testimony of the many different perspectives of survival during the Holocaust and the survivors’ lives afterwards. The whole series started by word-of-mouth. The USC Shoah Foundation took notice of the paintings and put me in touch with a number of survivors from all over the United States, Canada, and Europe. I received grants to travel to parts of the U.S. and abroad to paint some of the portraits.

SB: How did survivors react to your request to paint them?

DK: Some survivors refused to be painted either before or after seeing the preparatory sketches for the painting, while others loved to be painted and found it to be therapeutic. I’ve seen a full spectrum of reactions to both being painted and to the painting after it was complete. I believe that we think of ourselves as being in our early thirties or at a time when we were younger, and that self-image sticks with us. Because I’m painting them now and in a very raw and truthful way, it’s hard to confront that vision.

SB: How long were the sittings? Did you talk to your sitters about other subjects aside from their Holocaust experience?

DK: The interviews that were filmed lasted anywhere from an hour to a few hours. I would photograph them after the interviews in their homes. The interview went in whatever direction the survivors wanted to take it – it was very open-ended.

SB: Did you want the portraits to convey not just the survivors’ Holocaust experience but also their life after the Holocaust?

DK: Yes, I wanted to define them by their entire lives. I loved hearing about the large thriving families that most have built. These life-sized paintings strive to document each individual’s unique history, a sense of their experiences during the Holocaust, as well as their full lives, in an attempt to capture their spirit, pain, and dignity. It was important to me to focus more on the parts of their lives that they had control over after the Holocaust.

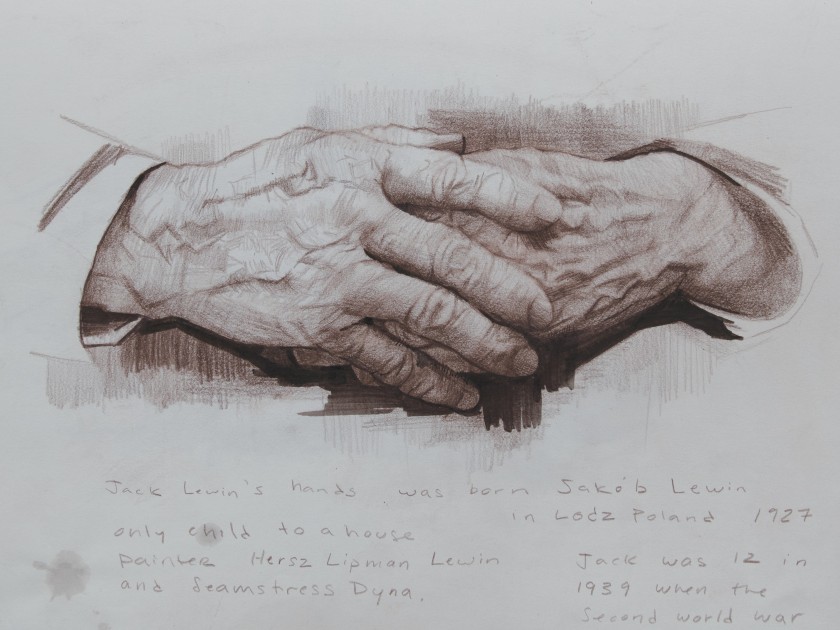

SB: How do these portraits function beyond capturing an individual’s likeness? In other words, what about the portraits portray the sitter’s Holocaust experience?

DK: I think that we, as human beings, have our skin as a barrier to our outer experiences and wear our lives on our faces, hands, and in our posture. What do the portraits portray of the sitter’s Holocaust experience? I’m not entirely sure. It may be how they hold themselves or in the way they choose to represent themselves, or it might be in what they choose to wear for the painting. Some survivors who sat for me held photos of loved ones who were murdered, as a way of speaking for those who can’t. In my portrait of Elsa Ross, she holds a photo of herself and her parents. It’s the only photo of them that she has, which was taken when she was only five years old. She was smuggled out of the Warsaw Ghetto in a workman’s truck and never saw her parents again. These paintings can’t encompass an entire life story but they can spark an interest, and hopefully the added context of filming can help to amplify these stories of survival. I believe that these paintings stand as sacred documents that serve as proof of these survivors’ existences.

SB: Were you a portrait painter before this series?

DK: I’ve always been into painting people since I first started making art. I grew up outside of Philadelphia and was always visiting the Philadelphia Museum of Art and learning a lot about the artists that painted and lived in the Philadelphia area. But, I don’t think of myself as a portrait painter. Although, the way I paint and the scale I use might lead folks to think I am because all my subjects are life-size.

SB: What is oil on acrylic mirror panel, the surface on which you paint, and why do you use it instead of a more traditional oil on canvas technique?

DK: I haven’t used canvas in forever. Canvas is too flexible a surface – it’s not archival enough for me. Oil paint, as it dries, needs to be on a sturdy and stable surface so that it doesn’t crack over time. The panels I use look like a regular mirror but are not made up of a real mirror, which would be very fragile. I found that this surface has more depth and luminosity, and I also love it conceptually in a number of ways. I love that the painting is a mirror and it slightly reflects the viewer; I think of the one-eighth-inch clear space in the painting between the surface and the mirror as a space for the survivor’s testimony to live.

SB: Please describe your meticulous technique. Do you work completely from life, like artists of the past such as Rembrandt, or do you also take photographs to which you refer? Do you paint straight on the canvas? Do you ever work from photographs projected onto the panel?

DK: My process is super meditative. I start with a charcoal drawing, blocking out the large forms, and then moving into smaller forms. I’ve been filming my process of these drawings and time lapsing them, and voicing over the testimony of the survivor that I’m drawing. These works are all done from photos I use as reference, not projected on the canvas, because I want to be as unobtrusive in my sitters’ lives as possible. By working from the photos, they don’t need to go through the sometimes grueling process of sitting for the hundreds of hours that I need to make a painting. With my other paintings, I try to work from the actual live model as much as possible. But most of the time, it’s a combination of both live sittings and photographs.

SB: Did you always paint from nature? How did your art develop into the kind of realism you are using now?

DK: I think that I paint towards my temperament and try to push past my comfort zone. I used to only paint from life but found it limiting. So I try to take the best aspects of what a photo can give me as well as what I’ve learned from painting from life. I use a photo as reference, versus painting the photo verbatim without thinking. As I learn to be a better photographer and a better painter, and learn more about the technology that I can use to get a better reference to work from, the more authentically I can paint my subjects.

SB: Is Facing Survival complete or do you hope to augment it with more paintings?

DK: So far, I have only painted and drawn a little over half of the survivors I have met. I also get lots of emails from survivor families through social media. However, I have been working on donations to get to certain places to meet folks, but in most cases I can’t see everyone that I would like to. There are survivors in Australia, Brazil, Shanghai, and South Africa that I would love to meet with, but they are outside of my means at this time. I’m also hoping to someday pull together all the video footage that I have been collecting from my trips into a documentary film.

Samantha Baskind is Distinguished Professor of Art History at Cleveland State University. She is the author or editor of six books on Jewish American art and culture, which address subjects ranging from fine art to film to comics and graphic novels. She served as editor for U.S. art for the 22-volume revised edition of the Encyclopaedia Judaica and is currently series editor of Dimyonot: Jews and the Cultural Imagination, published by Penn State University Press.