Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

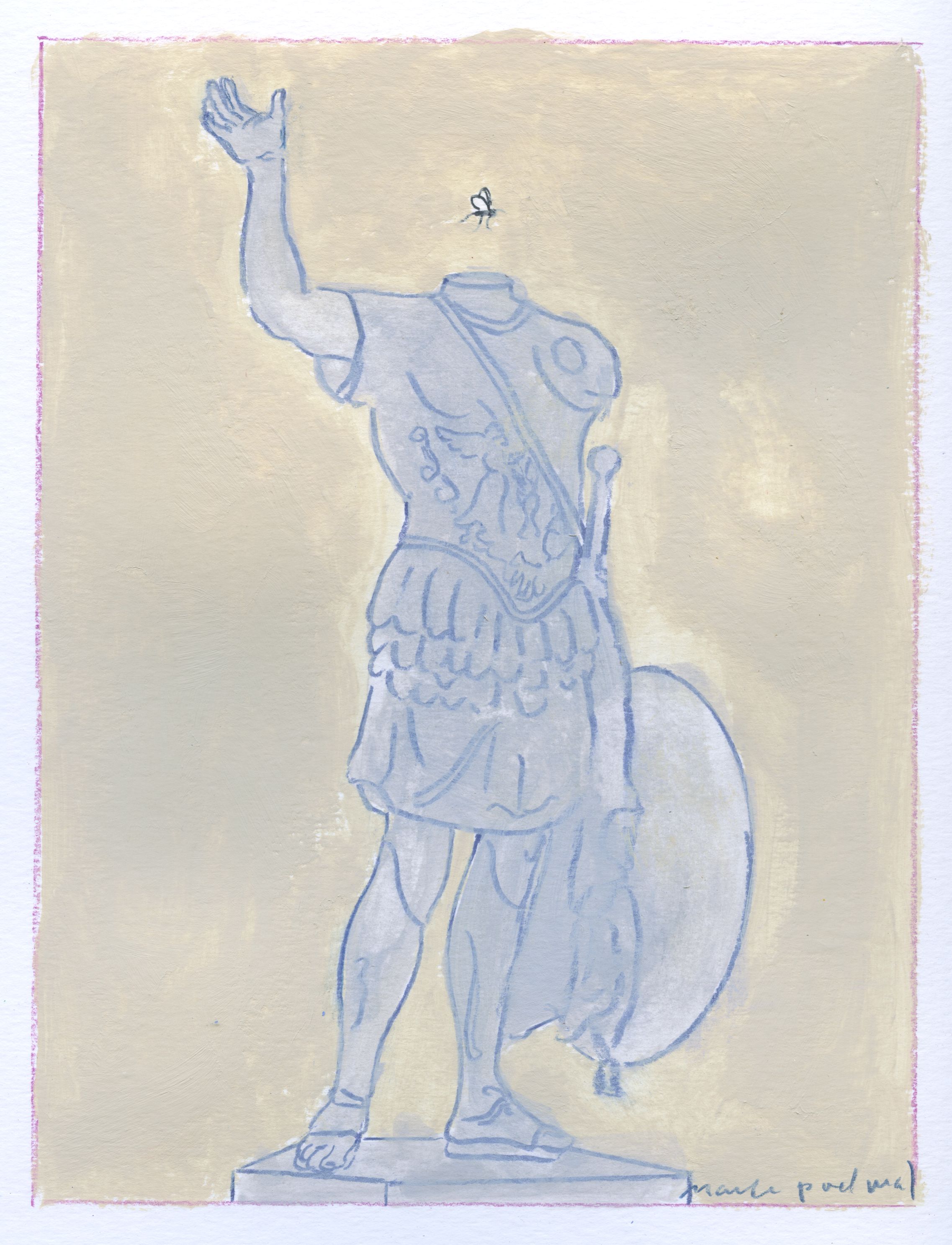

The rabbis tell us that many a species was created solely for the sake of a single member of its kind, to which some special historical mission was assigned. For example, the lowly gnat was called into being to cause the death of Titus, the Roman general who destroyed Jerusalem.

According to the Talmud, while Jerusalem was still in flames, Titus loaded the holy vessels of the destroyed Temple aboard a ship for transport to Rome so he could parade the spoils of his victory. On the sea a violent gale sprang up, threatening to sink the ship. Titus cried out, “The God of the Jews may have dominion over the waters, but if He is really mighty let Him come up on dry land and fight with me.” Whereupon a heavenly voice proclaimed, “Sinner and son of a sinner! There is a tiny creature in the world called a gnat. Go up on dry land and wage war with that!” (Gittin 56b). The storm subsided, and the ship proceeded on its way.

When Titus landed at Ostia, a gnat flew into his nose and entered his brain. The insect remained inside Titus’s head for seven years, buzzing incessantly. The suffering was intolerable. One day, as Titus was passing a blacksmith’s shop, the gnat heard the clanging of the hammer and ceased its activity. Believing that a remedy had been found, Titus ordered a blacksmith to hammer before him each day. If the blacksmith was a non-Jew, he would be given four coins; if a Jew, he would be told that it was compensation enough to see the suffering of his enemy. However, the remedy worked for only thirty days because the gnat grew accustomed to the hammering and resumed its buzzing.

The gnat grew in size each day, feeding on Titus’s brain until it finally caused his death. Physicians who opened his skull found a two-pound creature resembling a sparrow with a beak of brass and claws of iron, and they placed it in a bowl.

Titus’s remains were cremated. In accordance with his dying command, his ashes were carried to distant places and scattered over the seven seas so that the God of the Jews would not be able to find him and bring him to trial for the destruction of the Temple.

Yet another midrash says that Titus asked physicians to open his head in order to relieve the pain but asked them not to harm the insect so that all might see how God was punishing him. When they removed the insect, it was like a dove. It gradually diminished in size until it became an ordinary insect, which then flew away as insects do. And at that point Titus died.

Art by Mark Podwal

“Let them (the wicked) … be like a snail that melts away as it moves.” This imagery from the book of Psalms (58:8) stems from the ancient belief that the moist streak left by a snail as it crawls along is subtracted from its bodily substance; the farther it creeps, the smaller it becomes, until it wastes away entirely.

A more benign association is with the aromatic spice shekhelet, said to have been derived from the shell of a snail found in the Red Sea, which emits a pleasant odor when burned. Shekhelet was one of the ingredients, according to the book of Exodus (30:34), in the holy incense burned as an offering in the Tabernacle and later in the Temple. This fragrant offering is recalled in the ceremony of havdalah, performed at the conclusion of the Sabbath and festivals, when blessings are recited over a cup of wine, a lit candle, and spices (placed in containers that have been fashioned in a variety of forms).

Tekhelet is a blue-violet dye mentioned forty-nine times in the Bible. However, the Bible describes neither its source nor the means of producing it. Jewish tradition tells us that the only source of tekhelet is a sea creature known as the chillazon. The Midrash Tehillim describes the chillazon: “All the time that it grows, its shell grows with it” (23:3), which indicates the chillazon is a crustacean. Understood to be a species of snail, it is said that once every seventy years, a strong current uproots the chillazon, upon which the creature becomes inanimate and washes up on the shore; otherwise it must be fished out.

Tekhelet was used in the garments of the High Priest, the tapestries in the Tabernacle, and the tzitzit (fringes) affixed to the four corners of the tallit (prayer shawl). The fringes remind the Children of Israel to observe God’s commandments. According to kabbalah, tekhelet protected the wearer of the fringe, for the color blue wards off the evil eye. The Talmud notes that Rabbi Meir would say, “What distinguishes tekhelet from all other types of colors? It is because tekhelet is similar in its color to the sea, and the sea is similar to the color of the sky, and the sky is similar to the sapphire stone, and the sapphire stone is similar to [the color of] the Throne of Glory” (Chullin 89a). Remarkably, techelet was colorfast. Maimonides writes, “Its dyeing is well known for its steadfast beauty and does not change” (Mishneh Torah, Tzitzit 2:1).

Around thirteen hundred years ago, the knowledge of tekhelet procurement was lost or concealed. Thus a midrash lamented, “And now we have no tekhelet, only white” (Numbers Rabbah 17:5). As such, white fringes are worn until the coming of the Messiah, when Elijah himself will resolve all unanswered questions, including revealing the identity of the chillazon and how to make tekhelet.

Art by Mark Podwal

Mark Podwal has written and illustrated more than a dozen books, and has illustrated more than two dozen works by such authors as Elie Wiesel, Heinrich Heine, Harold Bloom, and Francine Prose. King Solomon and His Magic Ring, a collaboration with Wiesel, received the Silver Medal from the Society of Illustrators, and You Never Know, a collaboration with Prose, received a National Jewish Book Award. His art is represented in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum, Prague’s National Gallery, and the Jewish museums in Berlin, Vienna, Prague, and New York, among other venues. Honors he has received include being named Officer of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French government, the Jewish Cultural Achievement Award from the Foundation for Jewish Culture, and the Gratias Agit Prize from the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs.