Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

May 2021. Like Paris, Amsterdam is still partly under lockdown. My interview with the director of the museum, Ronald Leopold, takes place on screen. The conversation is crucial: he alone can authorize me to spend the night in the Annex. We talk about this and that, as a way of getting to know each other. Although he is glad Anne Frank and her story still mean something to people, he is sorry that all this adoration overshadows her writing.

Some people come every year, and have done for decades, to commune with her in her room. They leave letters, stuffed animals, rosaries, candles. It is not uncommon for a visitor to refuse to leave the Annex, convinced she is Anne Frank reincarnate.

This degree of identification perplexes the director. Calling her by her first name, as some of his colleagues do, troubles him as well.

Of course, working at the museum every day creates a kind of proximity to her, but Anne Frank is neither a family member nor a friend.

The conversation is crucial: he alone can authorize me to spend the night in the Annex. We talk about this and that, as a way of getting to know each other.

While we’re on the subject, he is by no means interested in making me fill out a questionnaire, but he would like to know: what does she represent for me?

I act as if my project were the fruit of a rational decision. I speak in a detached tone about my work, the young girls at the center of my novels: they all challenge the spaces they are allowed to occupy. All of them have seen their stories misinterpreted and rewritten by adults.

I’m improvising.

I don’t dare admit the truth, out of fear that Ronald Leopold will take me for a fanatic, obsessed with Anne Frank. I can’t explain to him that I don’t quite understand the desire for this writing project myself, which has been following me around ever since it showed up a few weeks earlier.

One night in April, two syllables — maybe I even said them in my sleep — slipped out of my childhood.

Anne. Frank.

I hadn’t been thinking of her the previous days or been reading anything about her. I barely remember the Diary. But during the night, her name emerges. Anne Frank keeps me awake. Nothing can dissipate the subject of Anne Frank during the days that follow. She is the echo of something I’m not quite aware of, yet.

I can’t admit to the director that I don’t know what exactly she means to me. Still: I have to write this essay.

Even through a screen, my unease must be palpable. Ronald Leopold reassures me there’s no need to answer him right away. That very night I write him an email. There are certainly “objective” reasons behind my desire to work on this project: like many children, I was given the Diary by my parents, and I began writing to be like her. My mother was hidden as a child during the war. I am Jewish. But I believe that all of that is unimportant, or at least it doesn’t quite explain my need to write this text. I finish my letter with a flourish, citing Marguerite Duras: “If we knew anything about what we would write before we did it, before we wrote, we would never write. It wouldn’t be worth the trouble.” It doesn’t take long for him to reply: Ronald Leopold suggests a virtual meeting with a retired academic.

Laureen Nussbaum is one of the last people alive to have known the Franks well, and she is also a pioneer in the field: she’s been studying the Diary as a work of literature since the 1990s.

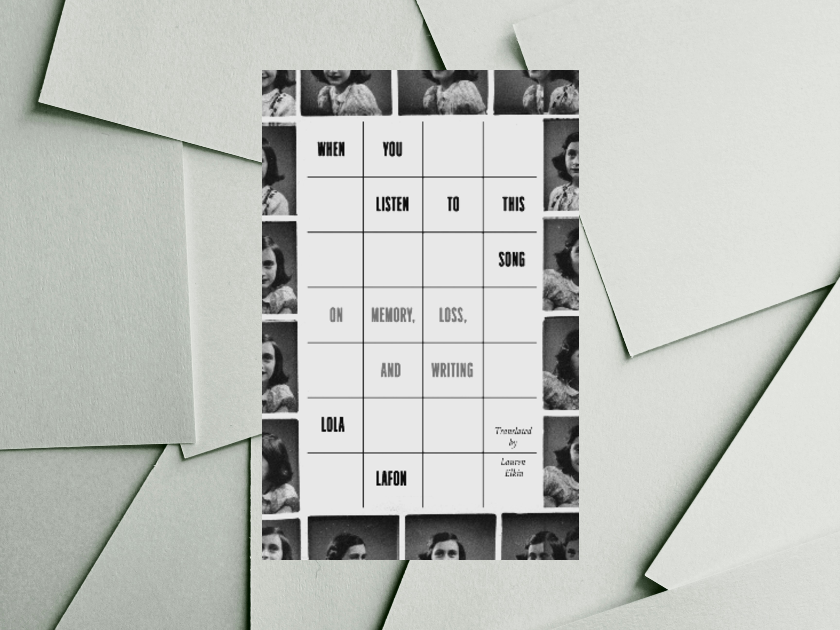

This article has been excerpted from When You Listen to This Song by Lola Lafon, translated by Lauren Elkin, new from Yale University Press. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Lola Lafon is a French writer who grew up in Eastern Europe and studied dance and music in Paris and New York. Her prizewinning books include The Little Communist Who Never Smiled and Reeling: A Novel. She lives in Paris, France.

Lauren Elkin is a French and American writer and translator. She is the author of several books, including Flâneuse and Scaffolding, and lives in London, UK.