Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

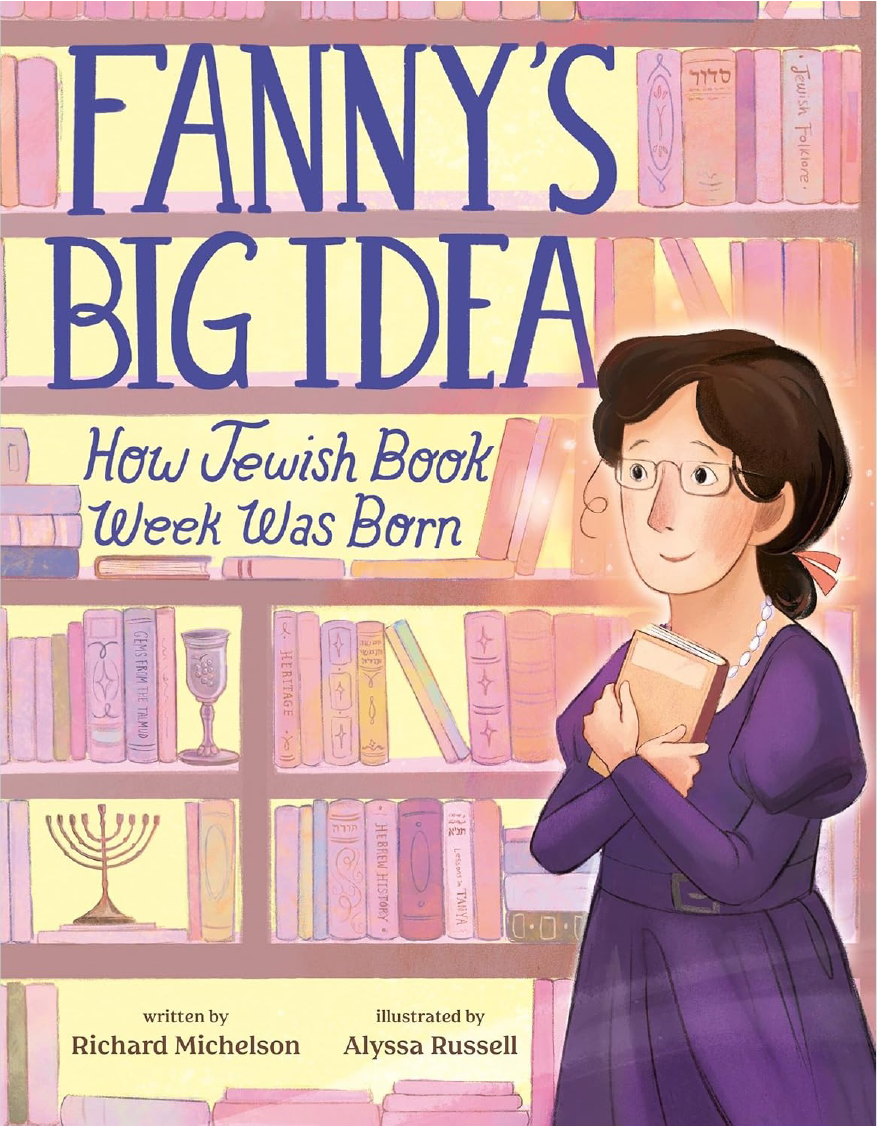

Art by Alyssa Russell

In 1925, in the West End Branch of the Boston Public Library, a Jewish Librarian had an idea.

Fanny Goldstein had immigrated from Russia as a child. Growing up in Boston, once each week she would walk to the North End Settlement House to learn American customs. She loved hearing about Thanksgiving and the Fourth of July. After class, she tried to share with her teachers about Sukkot and Shavuot, and Fanny could not understand why they seemed less interested in learning about different traditions than she was. But what mattered most to Fanny was that in America she could borrow books for free. She joined the Saturday Evening Girls Club and made friends with the neighborhood’s Catholic and Protestant girls from Ireland and Italy. She wrote in her letters, “When immigrants seek understanding and opportunity, they drift into the library.”

Fanny was the first librarian to champion what we have come to know as “windows and mirrors,” the belief that every person has the right to read about people like themselves, and the obligation to learn about other cultures. Her mantra was, “The more you know about someone, the harder it is not to like them.”

In 1921, at the age of thirty-three, Fanny was promoted to the job of Director of the West End Boston Public Library branch. She was the first Jewish person in the United States to direct a branch library. Neighborhoods in the area were in flux and Fanny added books by Black, Chinese, and Armenian authors as people arrived from across the US and overseas in order to reflect the population. She “ want[ed] to spread the idea that one can respect another person even though they are different.”

When Fanny made a list of which books had been checked out most often, she was surprised to see that 67% were children’s books. She loved Winnie the Pooh, The Wizard of Oz, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, and Heidi. But nobody was bringing home books about their own cultures. Many children couldn’t even name the country where their parents were born; their parents had been so busy learning American customs, they had forgotten or perhaps opted not to pass down their own family traditions.

______

It was November 1925, and with Hanukkah coming up, Fanny decided to host a week-long party at her library. She fried latkes, braised brisket, and baked noodle kugels. Friends brought Sufganiyot, hot chocolate, and cookies. Fanny wrote to the Boston and Jewish newspapers to announce her celebration. She set up a menorah and hung signs written in English and Yiddish. She even decorated a Christmas tree so that her non-Jewish patrons would feel welcome to join in the festivities.

The centerpiece of this celebration was a display of books that Fanny put together, composed of works by Jewish authors. It was the first collection of Jewish books to be exhibited in a public library in the United States.

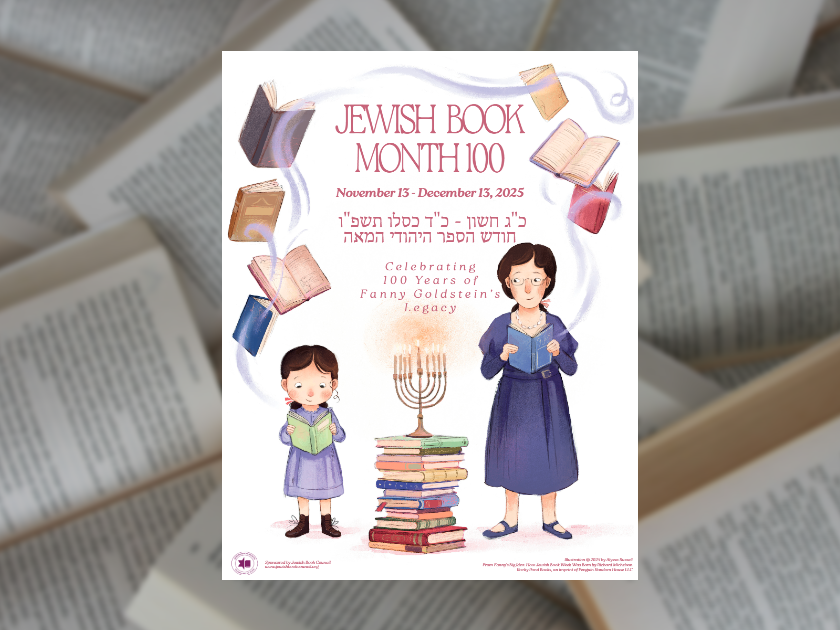

Jewish Book Week continued to grow each year, as more libraries around the country made their own displays and book lists. The National Committee of Jewish Book Week was founded in 1940, with Fanny as Chairperson. Three years later, Jewish Book Council was formed, and they expanded Fanny’s vision into Jewish Book Month, naming her Honorary President. The National Jewish Book Awards were established in 1950. Today, Jewish Book Council has over 120 partner organizations and arranges more than 1,400 programs each year through JBC Network. 2025 marks the 100th anniversary of Jewish Book Month (November 13 to December 13), which grew out of Fanny’s Jewish Book Week.

The centerpiece of this celebration was a display of books that Fanny put together, composed of works by Jewish authors. It was the first collection of Jewish books to be exhibited in a public library in the United States.

After the success of Jewish Book Week, Fanny would go on to host other celebrations of various cultures in her community. She even threw the opening pitch of a Boston Red Sox game when it fell during Jewish Book Week, though it never caught on.

In 1933, The Boston Globe reported that Fanny’s exhibits highlighting all of the nationalities represented in Boston’s West End community made her library “eagerly sought by hundreds, [trying to find an] understanding between the cultures of the old and new worlds.”

As her fame as a public speaker grew, Fanny’s opinions were often sought out and she used her renown to champion causes like women’s rights and democracy. If she were asked to give a speech or to write a critical essay, she insisted the pay be equal to that offered to men. If she found herself the only woman on a panel of experts, she would respond to the offer by suggesting, “Since modesty forbids me to dominate the feminine arena, what do you think about also inviting the following ladies?” She always had a list of women authors, critics, and librarians to share.

As she moved up the ladder of the public library system, Fanny faced both sexism and antisemitism head on. She wrote, “As a Jewess you have to compete not only 50 – 50, but a little more. I use the feminine gender because library work is definitely carried on by women. There are very few men in the profession — unless they are in executive positions at the very top — and certainly very few Jewish men.”

When Rabbi Felix Mendelsohn of Chicago claimed credit for starting Jewish Book Week, Fanny didn’t complain — it was the idea, not the glory, that was important. She thought more people might listen to a man, especially a rabbi. What she learned is that men wanted the glory, but didn’t want to do the work. She wrote in an editorial piece: “I am no longer angry. I am, instead overwhelmed with pity that a man supposedly trained as a rabbi … to interpret ethics and understanding, should …be so filled with pomp and arrogance and self-inflation so that he has to behave in a manner that would jeopardize the labors of another in Israel’s cause. He needs pity more than truth or logic.”

During the 1930’s, as Nazis burned Jewish books in Germany, Fanny spoke out with even more urgency about the necessity for books of all cultures to be available.

Throughout her career she also regularly visited local prisons to teach inmates about Jewish customs. She conducted Passover Seders for those incarcerated, and made sure to send them books.

Fanny retired from the West End Library in 1958. She died on December 26th, 1961. She never married and had no children, but she helped to raise generations of devoted book lovers.

Fanny’s Big Idea: How Jewish Book Week was Born by Richard Michelson

Richard Michelson’s books have been named among the Ten Best of the Year by The New York Times, Publishers Weekly, and The New Yorker; He’s received a National Jewish Book Award (and twice finalist) and two Sydney Taylor Gold Medals (and two silver) from the AJL. Born in Brooklyn, Michelson lives in MA and owns R. Michelson Galleries.