Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

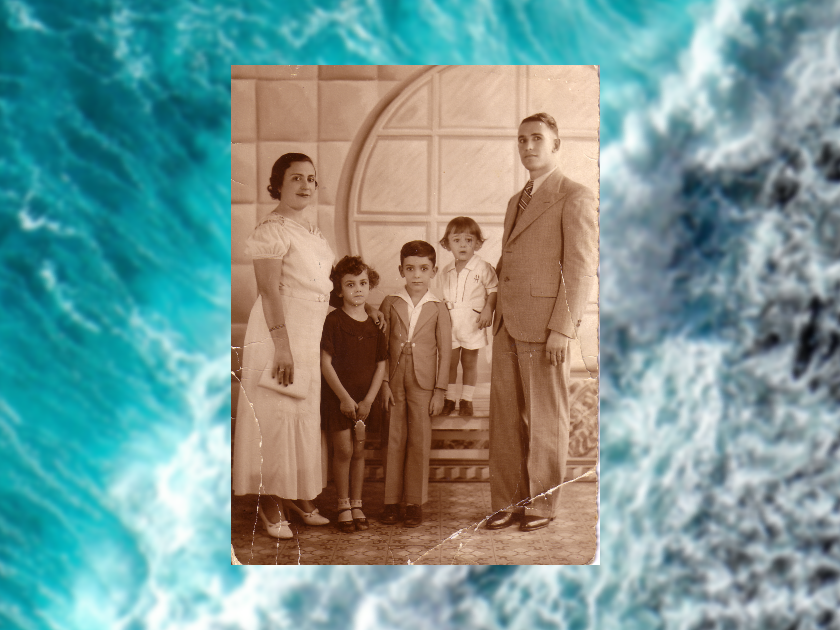

Author’s grandparents and their kids

All photos courtesy of the author

Before I began writing my new novel, Across So Many Seas, all I knew was that I wanted to write a story about four Sephardic Jewish girls, living in four different times in four different places. Somehow their stories would intersect, though I wasn’t sure exactly how. I wanted it to be a novel that kids as young as ten years old could enjoy and hoped it might have crossover appeal for adults.

These were the first notes I wrote to myself:

In each generation, a twelve-year-old girl is caught in the web of history:

Something all share — the dream of a just, tolerant world …

The words of a lost song …

A need to forgive …

The bonds of family …

And a heritage of seeking freedom that goes back five centuries to Spain …

With these sparest of notes as my guide, I came up with four characters: Benvenida, living in Toledo, Spain in 1492; Reina, living in Silivri, Turkey in 1923; Alegra, living in Havana, Cuba in 1961; and Paloma, living in Miami, Florida in 2003.

I drew inspiration from both the distant and more recent past. I was curious about how the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 was experienced by young people, especially girls. There is scant information in historical accounts, but I did find a 1492 chronicle penned by a Spanish priest who observed Jewish people taking to the road looking for a port from which to sail across the sea to a safe harbor. He felt pity for these expelled Jews and noted that there were priests along the way who offered them a last chance to be baptized so they could stay in Spain. But few accepted the offer. The rabbis, he noted, encouraged the community not to lose their faith, “and they made the women and young people sing and play tambourines and timbrels to keep up their spirits.”

This led me to imagine a Sephardic girl singing a Spanish love song and playing her tambourine as she leaves her beloved home of Toledo, Spain. I set this story in Toledo because, in medieval times, it was a city of great spirituality, where Jews, Christians, and Muslims coexisted in peace. In Toledo today, there is a beautifully preserved fourteenth-century synagogue that is now the Museo Sefardí, the Sephardic Museum, which I have visited many times and always found magical. And so the character of Benvenida — which means “welcome” in Spanish — was born. The book begins with her expulsion and departure. Heartbroken, she sings as she leaves, and her old friends, recent converts to Catholicism, throw rocks at her. But she is not simply a girl who sings. She is also a girl who reads and writes, having been taught by her mother, who comes from a family of printers. She secretly writes poems and tucks one into the wall of the courtyard of their home in the Jewish neighborhood of Toledo. Eventually, she and her family arrive in Constantinople (today Istanbul), where she hears an oud being played for the first time. She is drawn to its haunting sound and vows to learn to play it.

My other source of inspiration came from my paternal grandmother, Rebeca, my Abuela. She was a Sephardic Jew from the Turkish town of Silivri, on the outskirts of Istanbul. She had two younger sisters and a brother. In the mid-1920s, her family sent her alone to Cuba. Many years later, when she was old, she was reunited with her sisters, but she never saw her parents or brother again. A marriage, the story goes, had been arranged for her, but by the time she arrived in Havana, it was too late: the man had already married someone else. She went to live with an uncle, her only relative in Cuba. To pass the time, she sat in the entranceway of his building, sang Sephardic love songs, and accompanied herself on an oud she had brought from Turkey. Her singing attracted another Sephardic Jew from Silivri — a man named Isaac, who would become her husband and my Abuelo. They lived in a tenement on Calle Oficios, overlooking the port of Havana. From their balcony, they could see the ferry travel back and forth to the town of Regla across the bay. Abuelo was a peddler and made just enough to support their four children. My father, the third child, recalls seeing Abuela’s oud hanging from a nail on the wall of their apartment. He says she was too busy to play it or to sing.

This story stayed with me, and I wove all of it — the oud, the singing that attracted my Abuelo, the mystery of why Abuela was sent away, and the balcony looking out at the sea — into Across So Many Seas. Abuela’s story led me to imagine a melancholy Sephardic girl in Silivri named Reina (“queen” in Spanish), who tells her story in the second section of the book. Reina disobeys her father by singing and playing the oud for a group of neighborhood boys, daring to give herself more freedom than he thinks a girl ought to have. As punishment, he ships her off to Cuba. She is promised to a Sephardic man who will wait three years and marry her when she is fifteen. She brings her oud with her to Cuba, where she sings a song of a girl’s yearning for freedom, a song about a girl lost in the middle of the sea, which recurs throughout the book:

En la mar hay una torre

en la torre una ventana,

en la ventana una hija

que a los marineros llama

In the sea there is a tower,

in the tower there is window,

at the window a daughter

who calls to the sailors.

I then had to imagine who Reina’s daughter might be. I wanted a girl who would stand in contrast to Reina, and so Alegra (“joy” in Spanish) was born. It is the time of the Cuban Revolution, and Alegra is full of idealistic dreams. She’s excited to participate in a literacy campaign that will bring reading and writing to people in the countryside, and Reina gives her permission to go. After hearing the reason why her mother was sent across the sea to Cuba, Alegra is stunned by how things have changed for girls in her generation. She loves the work of teaching literacy, taking joy in watching people in the countryside learn to read and write. She never suspects that she will have to leave Cuba. But the authoritarianism of the revolutionary government soon catches up with her and her family. She too will cross another sea, to Miami.

Who, I wondered, would be Reina’s granddaughter, Alegra’s daughter, and a possible descendant of Benvenida? A girl named Paloma came to mind. She tells her story in the last part of the book, which connects all four narratives. Paloma, meaning “dove of peace,” is intrigued by old songs in Ladino, the endangered Judeo-Spanish language that her grandmother, Reina, grew up speaking in Turkey. Paloma is a keeper of memories: she holds on to every story that her mother has shared with her. Paloma is also connected to the African heritage of Cuba through her Afro-Cuban father, Rolando, a convert to Judaism. I was able to draw on my anthropological work interviewing Afro-Cuban Sephardic Jews in Cuba to fashion this part of Paloma’s identity.

When Reina, Alegra, Paloma, and Rolando go on a trip to Spain, they decide to visit Toledo. Paloma’s great-grandmother’s last name was Toledano; maybe, they think, they have a connection to this city. They make their way to the Museo Sefardí in Toledo, where the past and the present converge in eerie ways. An oud is waiting there to be discovered by Reina — as is a message from a distant ancestor, whom the museum guide, Mari Luz, thinks may have been named Benvenida. Mari Luz, who is Catholic, wonders if her own family might descend from hidden Jews. It is here that Paloma realizes that some of her ancestors may have been “conversos.” She marvels as Mari Luz lights Shabbat candles on Friday night to remember the Jewish people who were expelled from Toledo. I myself know Spaniards who celebrate Shabbat as a means of seeking historical reparation, and I find it a moving and hopeful gesture of allyship.

Author’s parents’ wedding dance, 1956

When I set out to write Across So Many Seas, I didn’t know how to write a novel told from multiple perspectives. I’d never done it before. But by writing, I taught myself how to write. The release date of the book is February 6, which happens to be my mother’s birthday. Against her Ashkenazi family’s advice, she chose — at the young age of twenty, in Havana, Cuba — to marry a Sephardic man, a “turco” with whom she had fallen madly in love. And because of that brave decision, I can claim a Sephardic heritage. So I owe the writing of this book to her in many ways.

Combining historical research about 1492 and my desire to honor the memory of my Sephardic grandmother, this book represents the deep respect I have for the many seas my ancestors crossed so I could be alive today. I release it into the world with the hope that it will uplift readers in a moment when our spirits are so in need of being lifted up.

Ruth Behar, the Pura Belpré Award-winning author of Lucky Broken Girl and Letters from Cuba, was born in Havana, Cuba, grew up in New York, and has also lived in Spain and Mexico. Her work also includes poetry, memoir, and the acclaimed travel books An Island Called Home and Traveling Heavy. She was the first Latina to win a MacArthur “Genius” Grant, and other honors include a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship and being named a “Great Immigrant” by the Carnegie Corporation. An anthropology professor at the University of Michigan, she lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.