Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Yosef was living in Odessa, Russia, one of three sons of Kiva and Rebecka Bendersky. Then Yosef’s two brothers were killed in the 1905 pogroms. Kiva said, “Enough.”

The family made secret plans to emigrate. After a two-thousand-mile railway journey crossing the Carpathian Mountains through tunnels, the Benderskys arrived at the Antwerp port. As the ocean liner S.S. Zeeland was boarding, they were suddenly told that the moneys that had been sent to cover their combination rail/steamship tickets to America were not sufficient. It was decided that Kiva and Rebecka would go first, to begin the process of staking claims for homesteading in North Dakota, as seventeen-year-old Yosef was too young to file a claim.

Yosef watched his parents walk by themselves onto the pier — before blending with hundreds of others, as colors in a dark watercolor painting. After he and his sister, Lena, had waited several months in a Jewish boarding house, funds for their ocean passage were sent. In 1906, they traveled to the United States in steerage on the Red Star Line. Yosef Bendersky, who became Joseph Bender in America, was my grandfather.

Dreams of the freedom to farm their own land pulled Joseph and his family directly to the midwestern plains, at that time called “the Great Northwest.” Unlike over seventy-five percent of their Jewish immigrant brethren, who stayed on the East Coast, the Benders boarded trains west to Eureka, South Dakota, and then traveled on to Ashley, North Dakota in carts pulled by oxen.

Unlike over seventy-five percent of their Jewish immigrant brethren, who stayed on the East Coast, the Benders boarded trains west to Eureka, South Dakota, and then traveled on to Ashley, North Dakota in carts pulled by oxen.

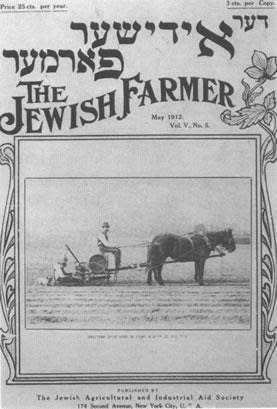

Joseph Bender, with single blade plow and horse on his homestead land near Ashley, ND, circa 1909. Photo taken by Jewish Agricultural Society representative.

After working for a farmer to learn the basics, Joseph turned twenty-one (or so he said) — old enough to file a claim for homestead land. The government provided him with 160 acres of surveyed land near Ashley. Homestead claimants could obtain title after living on their parcel for five years, cultivating the land, and building a dwelling. So almost immediately, Joseph had a decision to make: he could either build a dugout cave with no windows, protected from the moisture by horse manure, or a sod house, with a wooden door and real windows. Joseph opted for the sod house, with stacked bricks carved from native western wheatgrass.

Once in his new home, Joseph recited the ancient prayer Mah Tovu (“How beautiful are your tents, o Jacob, your dwellings, o Israel”), from the fourth book of Moses, Bemidbar, (In the Wilderness). Then he began the task of clearing some of the many rocks and stones that prevented crops from growing on his land. As the Jewish homesteaders had arrived in south central North Dakota twenty years after it was opened for homesteading, the only available land was sloping and rocky. Their welcoming German Russian neighbors called the area Judenberg (Jewish Hills).

Despite drought, prairie fires, early frosts, and blizzards, Joseph was successful enough to purchase his land outright for $200 in 1910, two years prior to the requisite five-year waiting period. He grew wheat and flax, raised cattle and chickens, and sold cream, along with working off the farm — building roads and working on threshing crews and the railroad. On Saturday nights after Shabbat, Joseph pulled a wagon filled with hay to pick up the Jewish single men and women. Quilts covering gunny sacks with heated rocks inside kept everyone warm. The ladies brought cakes and sandwiches for snacks, and everyone sang, bouncing their way along to the barn for a dance.

The same year he bought his farm, Joseph met raven-haired Mary Rievman in the general store. Born in Baltimore in 1894, Mary had left school at fourteen to work in a downtown department store, where she helped fancy ladies to select petticoats before those customers met friends at the tearoom for creamed salmon on toast or plombier. A short time later, Mary was sent to Wishek, a rural town near Ashley with four hundred people. She worked in one of her uncle’s general stores — mostly selling staples and household goods to the farm families.

After a short courtship, Joseph sold some of his flax crop, bought a suit, and headed to Minneapolis to ask Mary’s parents for permission to marry. Following the wedding, Joseph took Mary by horse and buggy to her new home, the sod house. Joseph lit the candles that were their only source of light. Mary unpacked her things and picked up a broom to sweep the dirt off the floor. But she couldn’t get rid of it. She fell to the ground and began to cry. Mary had realized that the dirt wouldn’t come off the floor because the floor was dirt.

Joseph and Mary Bender, Wedding Picture,1911, author’s files

She adapted quickly — cooking whatever food Joe could hunt and kill on the prairie, making wild chokecherry jelly, and filling the stove with coal every hour or two.

This incident could have foreshadowed a difficult future for Mary. But she was strong inside as well as out. She adapted quickly — cooking whatever food Joe could hunt and kill on the prairie, making wild chokecherry jelly, and filling the stove with coal every hour or two. She put feminine touches on their home — throwing flower seeds on the windowsills and on the roof so the place would be brightened when the flowers bloomed, and sewing proper curtains for the windows. Joseph proudly called Mary “a real farmer’s wife” when she, on her own, successfully sold one of their calves, so Joe could make the first payment on a life insurance policy.

Mary and Joe eventually sold their homestead land and rented a store thirty miles away, on the main street in Eureka, South Dakota; the awning proudly proclaimed, “Benders Farmers Cash Store.” When Mary would wait on a customer who wanted to purchase some boots or coats, the customer would ask Mary how much they were. Mary would call to Joe in the back, “How much are they, Joe?” “Who is it, Mary?” Joe would respond. If the customer was a farmer down on his luck after a difficult year, the items were sold near cost.

Der Iddisher Farmer (The Jewish Farmer) Magazine, Vol. V, No. 5, May 1912, published by The Jewish Agricultural Society, with advertisements in Yiddish

Despite being the only Jews in Eureka for most of the over thirty years they ran the store, the Benders never felt a need to hide their religion. When Rosh Hashanah was approaching, Mary made signs: “Closed for Jewish High Holidays.” They would head off with children in tow to pray with fellow Jews. Their customers were back when they were. Joe Bender even served on the school board, as an alderman, and as mayor of the town.

I came to know my grandma Mary and my grandpa Joe many years later, when we were all living in Minnesota. Joe was retired and smoked a cigar, even while playing golf. He liked corned beef on dark pumpernickel and loved America. He seemed to miss his days of traveling on horseback, dust flying, to make a minyan in North Dakota. He returned frequently to the Dakotas, to recite the Mourner’s Kaddish at the Ashley Jewish Homesteaders Cemetery, where his father, Kiva, was buried, and to visit old friends.

My grandma Mary appeared to be so gentle, with her long black braid pinned up carefully, reading stacks of books to my sister Nancy and me. But I knew she had hidden strength. After all the years at the Eureka store, she could still open a box like nobody’s business: if a box were taped closed, she would pound the side of her fist close to the tape, and then rip up the other side, revealing its contents.

In her later years, Mary was knocked down by a robber while walking home from the downtown Minneapolis bus. Having gone from her big city life to a rural existence cooking pheasant in a sod house, and then raising five children while working in the family store, she did not let this incident stop her. My grandma continued to take the bus downtown to purchase matching dresses for Nancy and me, oftentimes in yellow, her favorite color, “like the sunshine.”

When facing a challenging situation, I find koich (strength) from Mary and Joseph — an ever-replenishing supply of gold from the prairie. By documenting my ancestors’ stories, I also follow their example in sharing the gifts I’ve been given.

Rebecca E. Bender, who wrote this piece, and her father Kenneth M. Bender are coauthors of Still (NDSU Press 2019), a biography/memoir of five generations of their Jewish family on three continents. Still is the 2019 Independent Press Award Winner (Judaism category) and the 2020 Midwest Book Award Gold Medal Winner (Religion/Philosophy category). Rebecca’s prose and poetry have appeared, inter alia, in The Journal of The American Historical Society of Germans from Russia, North Dakota Quarterly, The Jewish Veteran, the Forward, Australia’s Jewish Women of Words, the StarTribune, Mandala, The Northwest Blade, The San Diego Jewish World, and previously in Paper Brigade Daily (Jewish Book Council). She has recently completed two other projects: a Still screenplay adaptation and a children’s storybook, based upon fact, about a young Jewish girl living on the prairie with her homesteading parents in the early 1900s, with each story focusing on a core value of Judaism. Still, with a second printing out in paperback in March, is available through NDSUPress.org, Amazon.com, or can be ordered through any bookstore.