Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

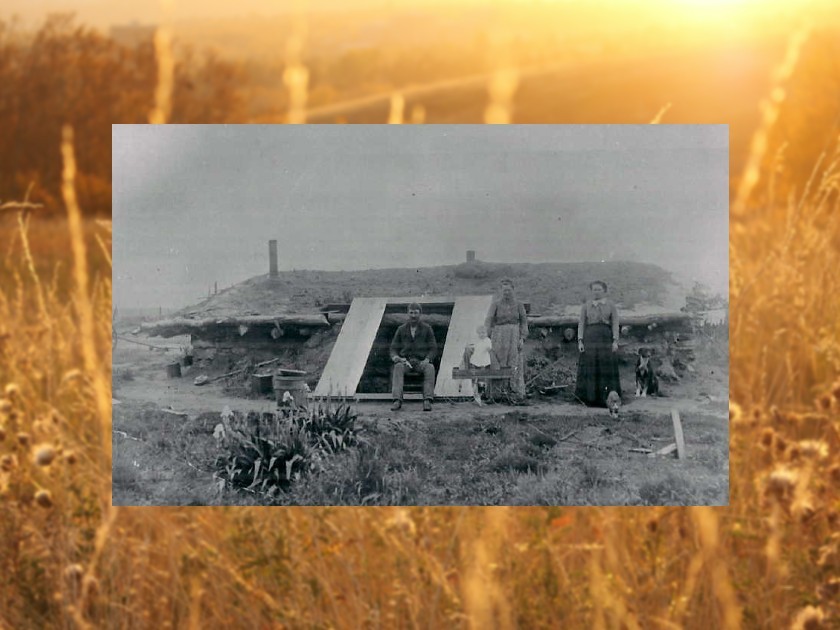

John Pettit, Emma Mae Geiger Pettit, Julia Etta Geiger, and Arvil Pettit (baby) in Longdale, OK, 1904. Photo courtesy of Sandra Greer

Were there Jews on the prairie?

My most recent middle-grade novel, A Sky Full of Song, began as I sat at my laptop studying a photograph of homesteaders in front of a dugout. As I was gazing at the photo, I began to wonder about homesteading in relation to American Jewish history. My attention was caught by details like the irises planted in front of the rustic home, the homemade baby carriage, and the dog and the cat who had clearly been put in place to pose for the photograph (although the cat, unsurprisingly, was busy stalking off).

Had any Jews ever taken advantage of the Homestead Act of 1862, I wondered. Had Jews ever struggled to farm the land and lived in earthen dugouts? Had there ever been any little Jewish girls running around the prairie like Laura Ingalls Wilder and her sister Mary, or like the young Willa Cather? It seemed incongruous with the history and stories we all learn in school even to imagine it!

I began to do research. I quickly learned that some Jewish refugees who came from the Russian Empire to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries did make the choice to homestead. Most settled in East Coast cities or perhaps farther west in Chicago. Theirs are the classic turn-of-the-twentieth-century Jewish immigrant stories we all know so well.

But not every Jew wanted to settle in a city. Some Jewish immigrants wanted to farm. And the Homestead Act of 1862 even seemed to offer the promise that they could eventually own land of their own — if they could “prove it up.” This entailed paying a filing fee, living on the claim land, building a home, farming, and making specified improvements.

For some Jews, this was an irresistible opportunity. Most of the Jewish homesteaders arrived in the early years of the twentieth century, relatively late in the homesteading era. Most settled in North and South Dakota, sometimes in community groups or in extended families .

But often the land that was left to claim wasn’t particularly good for cultivation, and farming it was a huge challenge. The Jewish Agricultural Society, one of Baron de Hirsch’s charities, helped with equipment and funds as the farmers struggled.

As an English professor as well as a children’s book author, I have written scholarly works about literature and history. But when I began writing historical novels (A Sky Full of Song is my third), I quickly learned how much more deeply I needed to know history to write historical fiction. Most of the questions a historical novelist needs answered are highly specific questions about daily life, and such questions are not answered by broad, sweeping works of academic history.

I quickly learned that some Jewish refugees who came from the Russian Empire to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries did make the choice to homestead.

But these were the questions I needed to answer in order to write my novel about eleven-year-old Shoshana Rozumny, her parents, her older brother and sister, and her twin three-year-old sisters, as, in 1906, they flee Liubashevka (modern-day Ukraine, at that time part of the Russian Empire) and begin homesteading in a North Dakota dugout. Shoshana delights in the wild beauty of the prairie and her family’s new animals, especially her kitten Zissel, found and rescued on their long train trip from New York. But she also struggles to find her way in North Dakota when her family encounters tentative offers of friendship from some settlers and overt hostility and prejudice from others.

I wondered – what simple, cheap food would a family like Shoshana’s have eaten on the prairie? What would Jewish women from a small village in Ukraine have told their daughters about menstruation? How observant would they have been — and would they all have remained so under homesteading conditions? Did babies wear diapers? Is it possible to paint or paper the earthen walls of a dugout? What did Jews do for candles on the North Dakota prairie? Some of these questions were challenging to answer. Often even scholars I asked didn’t know!

Then there were the bigger questions. What particular challenges did Jewish homesteaders face? Did they face antisemitism and what forms did it take? What encounters might there have been between Jewish settlers and the Indigenous peoples of the plains?

To answer questions like these, I turned to personal memoirs, individual accounts of family history, recorded and transcribed oral histories, newspapers from the time, and several contemporary journalistic accounts.

As I researched, I found some particularly useful works that others interested in learning more about this little known piece of Jewish American history may enjoy.

Rebecca E. Bender and Kenneth M. Bender’s Still was a book I read with great attention. It is a compelling, deeply researched and contextualized history of five generations of the Bendersky family as they fled oppression in Odessa to take up new lives in the Dakotas.

Rachel Calof’s Story, edited by Sanford Rikoon with an epilogue by Jacob Calof, was also tremendously helpful to me. In 1936 Rachel Bella Kahn Calof wrote this account of her life story, including her journey from Kiev to North Dakota, her arranged marriage to Abraham Calof upon arrival, and the years they spent homesteading in dire conditions. Her children had the Yiddish memoir translated and ultimately agreed to its publication in 1995. It’s a fascinating and sometimes very disturbing account of her arduous experience.

Sophie Trupin’s Dakota Diaspora: Memoirs of a Jewish Homesteader is another first-hand account that I treasured. Sophie Trupin came as a child to the Dakotas, and her account of her memories is keen-eyed, detailed, and poetic. It was a delight to immerse myself in it.

The story of the Jewish homesteaders is a fascinating, complex one. While I was writing A Sky Full of Song, I often jokingly thought of it as my “Little Jews on the Prairie” novel.

Yes, Jews were there too. And my novel imagines one family’s experience on the plains.

Susan Lynn Meyer is the author of two previous middle-grade novels—Black Radishes and Skating with the Statue of Liberty—as well as three picture books. Her works have won the Jane Addams Peace Association Award, the New York State Charlotte Award, and the Sydney Taylor Honor Award, among many others. She is Professor of English at Wellesley College.