Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

My mother died when I was twenty-six. We spent her last month together, talking about our lives as cancer eroded her strength. After she died, I remained in her home, in the Hudson Valley, in her woods, alone, despondent, in the darkest moment of my life.

One night, a book put its arms around me and held tight. After a long time, the book released me from its hug, took my hand, led me to my writing desk, and suggested that I tell my own story about a mother and son.

The book was Amos Oz’s A Tale of Love and Darkness. To me, Oz’s memoir stands as the greatest modern variation in the long tradition of the Jewish mother-son story.

Oz wrote Tale in his early sixties. His mother, Fania, died half a century earlier, when he was twelve. She was thirty-eight. Oz writes about his mother from the many vantage points from which he knew her. The young boy who was her son. The grieving teenager who felt betrayed by her suicide. The man who has grown to her final age and seeks to look her in the eye as a peer. The artist who has lived long enough to be her father. Amos’ life is an orbit around Fania. He understands her more deeply with each revolution.

In those months after my mother’s death, I felt heartbroken by the idea that she and I would have no more chance to know one another. Reading Oz’s Tale helped me see that I, too, could continue to understand my mother more deeply, even after her death. That between the living and dead there remain ladders of language and ladders of love.

Fania and my mother, Fran, would have liked one another. They were each storytellers. As young women, each yearned to become an artist. My mother spent her twenties acting in Chekhov and Ibsen plays in New York City; Fania studied philosophy at Charles University in Prague and dreamt of becoming a writer. Each was frustrated in her ambition by the sexism of her time, the expectation that women should be readers rather than writers, listeners rather than talkers. Each gave her love of literature to her son.

When I met young Amos in Tale, I recognized a boy who, like me, had been raised on stories, dreaming of “places where godlike men fell in love, fought each other politely, lost, gave up the struggle, wandered off, sat drinking alone late at night at dimly lit bars in hotels on boulevards in rainswept cities.” Amos grew up imagining an adventurous life abroad, one worthy of a story.

I did, too. My mother raised me on fourteen acres in the woods in the Hudson Valley. My friends were our chickens, dogs, rabbits, and horses. Like Amos, I grew up on books. On the sofa by our fireplace, in the hammock beneath our pine trees, in the darkness of my bedroom as I fell asleep, my mother read to me from Robin Hood and King Arthur and Harry Potter. Her words created my world.

Oz tells us that his mother’s stories were: “Strange, frightening…captivating …veiled in a kind of mist.”

Fania never spoke about the Shoah, in which nearly everyone with whom she had grown up with was murdered. She put her pain and hope —her love and darkness — into stories.

My mother, too, chose not to tell me a great deal about her life. Only when I was in my twenties did she begin to speak to me about the experiences that had led her from life as an actress in New York to the world she made for us in the woods.

Only now could I see that my childhood in my mother’s home, in these woods, with her stories, with our animals, in a life made from her courage to follow her heart far from the conventional and expected — that is what had made me who I am.

Like Amos, I felt for many years that my home, my mother, and my life were not interesting enough for a book. I felt, like him, that, “Surely to write…you had to get out of here into the real world…Paris, Madrid, New York, Monte Carlo, the African deserts or the Scandinavian forests…”

I left home as soon as I could. I lived in Oxford, Berlin, Jerusalem. I drove across the United States three times. I backpacked through Europe and Asia. I returned home only when my mother told me she was sick.

In Tale, Oz tells of reading Sherwood Anderson’s short story collection Winesburg, Ohio, which narrates the lives of ordinary people in an unheard of town. Only then did Oz begin to understand that “the written world does not depend on Milan or London, but always revolves around the hand that is writing, wherever it happens to be.”

Reading Tale in my mother’s home, in the months after her death, was my own journey to Winesburg. For years, I had convinced myself that my early life had been dull, that what was interesting about me was the adult adventures I had made for myself. Only now could I see that my childhood in my mother’s home, in these woods, with her stories, with our animals, in a life made from her courage to follow her heart far from the conventional and expected – – that is what had made me who I am.

When I named the narrator of my novel, I chose my middle name, Evan. That felt right: the character is part of me, not all of me. For the last name, I chose Klausner, the name Amos Oz was born into and left behind when he became himself. He didn’t need that name anymore, but I did. One man’s detritus is another’s treasure. Thank you, Amos.

My mother often said to me: “We are here to take the pieces of the universe we have been given, burnish them with love, and return them in better shape than we received them.” In the last days of her life, she told me that she believed this was the best reason to tell a story. To redeem what is broken in our world.

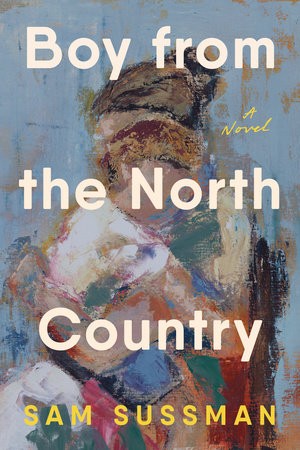

My novel, Boy From the North Country, will be published on September 16, eight years to the day she died. The journey to writing a novel about my mother’s life is over. The journey to knowing her more completely will never end.

Boy from the North Country by Sam Sussman

Sam Sussman is the author of the USA Today bestselling novel Boy From the North Country. The book was named Oprah’s most anticipated debut novel of the fall, hailed by Kirkus as “the most beautiful and moving mother-son story in recent memory,” and Sam was recently profiled in the New York Times. Boy From the North Country is based on Sam’s Harper’s Magazine memoir “The Silent Type: On (possibly) being Bob Dylan’s Son.” Sam graduated with a BA Swarthmore and M.Phil from Oxford and has lived in Jerusalem and Berlin. He lives in the Yorkville neighborhood of Manhattan and his native Hudson Valley.