Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

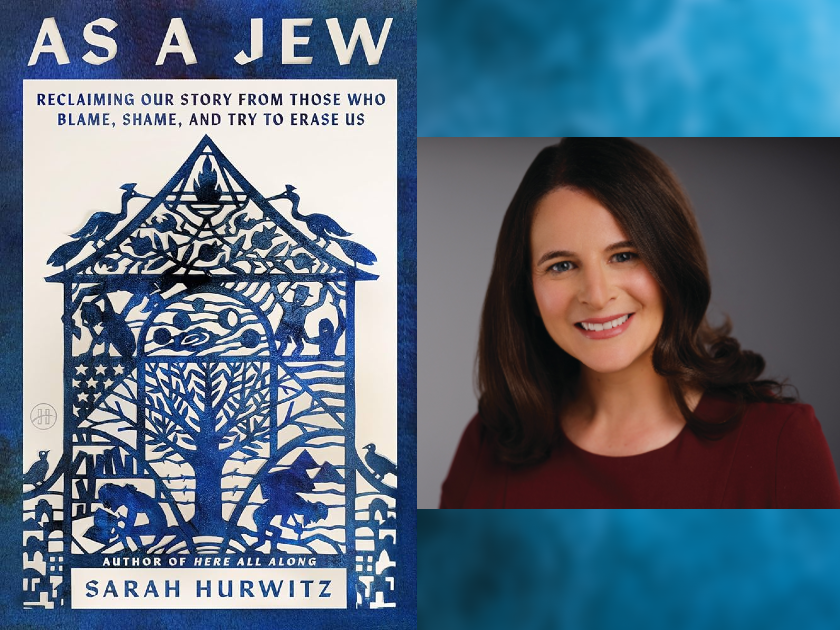

Author photo by Violetta Markelou

Rabbi Marc Katz, author of Yochanan’s Gamble: Judaism’s Pragmatic Approach to Life, spoke with Sarah Hurwitz about her illuminating new book, As a Jew: Reclaiming Our Story From Those Who Blame, Shame, and Try to Erase Us. They explored Hurwitz’s impetus for writing the book, the research she undertook in examining Jewish identity today, and how antisemitism shows up in our modern world.

Rabbi Marc Katz: Let’s start with the obvious, why did you write the book?

Sarah Hurwitz: There were actually a few factors that came together that led me to write it. The first one was that during COVID, I started doing training to become a hospital chaplain. Most of my classmates and all of my instructors were Christian. I started noticing that many things that I think of as Christian, they thought of as Universalist. We would talk about our ministry, our theology, and I was expected to just spontaneously and extemporaneously compose a prayer at a person’s bedside. When I tried to explain that not many Jews pray that way, they’d say that as long you don’t say Jesus, it’s universal. I began to realize just how soaked I was in Christian language, ideas, images, values, even the idea that spirituality means that our bodies and this world are carnal and somehow inferior to our soul or an incorporeal spirit realm.

Then the second thing was that well before October 7th, I visited a college campus, and I spoke at the Hillel. When I finished giving my talk, this student raised her hand, and she said to me, “So how did you deal with antisemitism when you were in college?” At first I didn’t understand the question. She had to ask it again, and I said, “I didn’t. Not once, not ever in the 1990s did I ever confront anything like antisemitism.” And the kids were so stunned. I think they almost didn’t believe me. They kind of looked a little skeptical. And then they started sharing stories of times when they had felt really uncomfortable on campus as Jews.

I really began reflecting on the different Jewish identities I carried for most of my life. I would say things like, “I’m just a cultural Jew.” But I didn’t mean I was actually a cultural Jew. There are many people who are cultural Jews who are deeply engaged in Jewish literature, art, thought, or Israel. They really have a deep connection to Judaism, maybe not through spirituality or religion, but through other aspects of Jewish culture. I knew nothing about Jewish culture. Or “I’m an ethnic Jew,” which literally is nonsense. Jews are of just about every ethnicity and just about every race, so that doesn’t even make sense. Or I’d say, “social justice is my Judaism.” There are indeed many Jews who are deeply versed in what Jewish tradition says about social justice, and they are living that out in their lives, which is such a beautiful way to be Jewish. However, I did not know anything at all about what Judaism said about social justice. Or finally, I’d say, “I remember the Holocaust.” Or “I’m against antisemitism,” which is a bummer of a Jewish identity, to identify essentially, as an anti-antisemite.

I really began to think in recent years about why my Jewish identity consisted of this series of caveats, apologies, embarrassments, conditions. Why was I always trying to sand the edges off? Why was I always trying to diminish my Jewish identity? And this book is my attempt to find an answer to that question. It really is an exploration of how thousands of years of anti-Judaism and antisemitism led Jews to try to escape that persecution by assimilating, watering down our traditions in the hopes of being safe and accepted. And, spoiler alert, it didn’t work.

MK: One of the things I admire about your book is that you really challenge Jews to take up space especially because we sometimes struggle with knowing how much space to take up. I’m wondering if that has something to do with your title. Can you explain, “As a Jew,” because it feels like it is giving permission for your readers to take up a little bit more space.

SH: I should give credit to the person who came up with this title which was the Israeli journalist Amir Tibon. I was telling him about the book and he asked if I had a title, and I said, “no, I’m terrible at coming up with titles.” He said “how about as a Jew?” I like that title because I think for so much of my life, I was saying I’m just a cultural Jew or I’m this kind of Jew, or I’m not that Jewish, but what if I was that Jewish? Would that be a problem? This title is a declaration of saying, no, I’m a Jew, as a Jew. No caveats, no apologies, no excuses.

MK: Let’s talk about the structure of the book. Your book includes a number of personal anecdotes. It’s the way you frame a lot of your chapters. For example, you talk about your time as a chaplain and then you move into some kind of issue that came up as a chaplain that frames your next argument. Why did you choose to write the book in that particular way, with that structure?

SH: I think that in a way, I am kind of relatable to many American Jews, because I didn’t grow up with a lot of Jewish background. It was three boring holidays and one fun one. It was two texts: a prayer book in your hand and Torah on the scrolls. Then we add a handful of universalist values like don’t lie, cheat, kill, be nice, all of that. And so, I think that hearing about Jewish history, about antisemitism, about Israel, from someone who has that similar background means you’re actually hearing it from a person who’s wrestling with it. I think that is a lot more accessible and relatable than a book with a bunch of facts and history that I’m going to drop on you. I just don’t think that those books are as engaging. I think it kind of leaves people cold. I’m not an academic. I am a Jew who’s grappling with this stuff, and I really wanted to bring readers along with me. I wanted to feel like they were on my journey.

MK: It really does feel like we’re going on a journey with you. You’re discovering things through your research, and then you convey them. I’m wondering, what were some of the most powerful ideas that you encountered when writing the book that you didn’t know before?

SH: Often we think of antisemitism as a kind of personal prejudice. Jews are cheap, greasy, aggressive, I don’t want one in my club, I don’t want my daughter to marry one. You don’t see that so much anymore in the places where many Jews live. But what you do see is a kind of political antisemitism, and this language comes from a philosopher named Bernard Harrison. The idea is that the majority feels they are engaged in some grand moral project and the only thing stopping them are the Jews.

For example: We the Christians, are Christianizing the Roman Empire, and the only thing stopping us are these Jews who refuse to convert. We, the communists, are bringing about the revolution, the brotherhood of man. The only thing stopping us are these capitalist Jews. We, the German citizens, are bringing about this great Aryan, racially pure fatherland, what’s stopping us? These race-polluting Jews.

And today, you see this in America on both the right and the left. On the right, you see, we, white Christian Americans, are bringing back white Christian civilization, and the only thing stopping us are these Jews who are bringing in Black and Brown immigrants to replace white people. It is called the Great Replacement Theory, and you see that a lot on the right.

On the left, you see people saying we are trying to fight for anti-colonialism, anti-racism, and the only thing stopping us are these Zionists who are fighting for their colonialist, racist state.

I am a Jew who’s grappling with this stuff, and I really wanted to bring readers along with me. I wanted to feel like they were on my journey.

MK: That reminds me of the important distinction you offer in the book between “Purim antisemites” and “Hannukah antisemites.”

SH: Dara Horn writes brilliantly in People Love Dead Jews, that there are different kinds of antisemitisms. There is the eliminationist kind that we all learn about in school, which says “you’re a Jew, you’re bad, so I’m gonna kill you. There is nothing you can do to be saved.” But there’s also a conversionist kind of antisemitism, which says “you are a Jew, you’re bad, but there is something you can do to be saved,” which is that you can give up whatever aspect of Jewish civilization that the majority finds disgusting. Back in the day, it was Jewish religion. If you convert to Christianity you might be saved. For my grandparents and parents’ generation, it was to give up your last name, give up your nose, be less, “Jewey,” be a little more waspy, and then you can be saved.

I think the demand for a lot of young people on college campuses today is to give up your connection to your ancestral homeland. If you give up your connection to Israel, then you’re acceptable. If you are anti-Zionist, then you’re saved. And I think you even see the kind of conversion narrative for some of these kids on campus where they say, “growing up, I was taught by my parents and my Hebrew school teacher and my Rabbi that Israel is a magical utopia of rainbows and moonbeams, and it’s perfect and then I came to campus, and I learned that it’s actually a racist colonialist state. I had an epiphany. I saw the light. I took anti-colonialism and anti-Zionism into my heart, and now I’m saved.” And they get the message from their classmates that they are now a “good Jew.”

Antisemitism gets upgrades. The medieval Christian clergyman did not think of himself as some sort of pagan xenophobe. He had centuries’ worth of very sophisticated theology telling him that Jews killed Jesus and they were evil. In later generations the nineteenth-century European scholar was never going to say that Jews killed Jesus. That was medieval, superstitious nonsense. They now had racial antisemitism, and it was “scientific”. That’s what you learned at the university. Today, no one is going to say that Jews killed Jesus, or are polluting the race. That’s outrageous. But the problem is Zionism. It’s the Jews’ nation that actually is the problem today. When you’re in an upgrade, it’s very hard to see it as antisemitism You still think antisemitism is the last thing.

When we teach our kids antisemitism by teaching them only about the Holocaust we are reinforcing that problem. They learn that the Germans blamed the Jews for losing World War I and for the Depression and then they killed them. Why? Because of bigotry and scapegoating and prejudice. But it never quite answers the question: Why the Jews? The real answer is because 2,000 years of Christian anti-Judaism wore a neural groove into the Western world’s mind that led to the kind of antisemitism that caused the Holocaust. But good luck teaching that in an American public school where saying happy holidays instead of Merry Christmas can get you canceled.

MK: So what worries you the most about antisemitism today?

SH: How incredibly insidious it is, and how incredibly prevalent it is across the political spectrum. My friend Dara Horn very astutely pointed out that if you think there are sides here you’re not understanding what’s going on. It’s the same narrative on both sides. Jews are preternaturally disproportionately powerful and are deeply depraved. They’re in a conspiracy to harm you. And you see this on both the right and the left. It’s sort of the horseshoe theory, where both ends of the horseshoe start to come together, and as I write in my book, it kind of takes on the shape of a noose. So that makes me quite worried.

MK: And so what can be done?

SH: Illiberalism is a huge problem, and often leads to antisemtisim. When you no longer have the rule of law, when you no longer have rational processes, when you no longer have people looking at data and evidence to make decisions, and instead people are going to old prejudices, I think that’s when you start to see antisemitism really increase. I think one of the most important things we can do is fight for liberalism. It’s not sexy at all. I hear people saying, some political action is good because it benefits the Jews and I say, “what if someone else with a sensibility that was on the other side of the aisle started doing that against Jews?” They respond “that would be terrible.” Well, that’s your answer. Anything that you do to others can then be done to you. That’s the problem with illiberalism. Liberalism means there are fair rules and procedures by which we are all held accountable and kept from hurting each other, so I think that promoting liberalism is very, very important.

MK: Final question — if you had one message for your readers to walk away from this book with what would it be?

SH: The Jewish tradition has so much to offer, not just to Jews, but to our world, and I think to access it, we really need to strip away a lot of layers of antisemitism and anti-Judaism that have turned us against our traditions and led us to misunderstand Judaism. We need to reclaim our tradition on its own terms.

Rabbi Marc Katz is the Rabbi at Temple Ner Tamid in Bloomfield, NJ. He is author of the books Yochanan’s Gamble: Judaism’s Pragmatic Approach to Life (JPS) chosen as a finalist for the PROSE award and The Heart of Loneliness: How Jewish Wisdom Can Help You Cope and Find Comfort (Turner Publishing) which was chosen as a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award.