Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

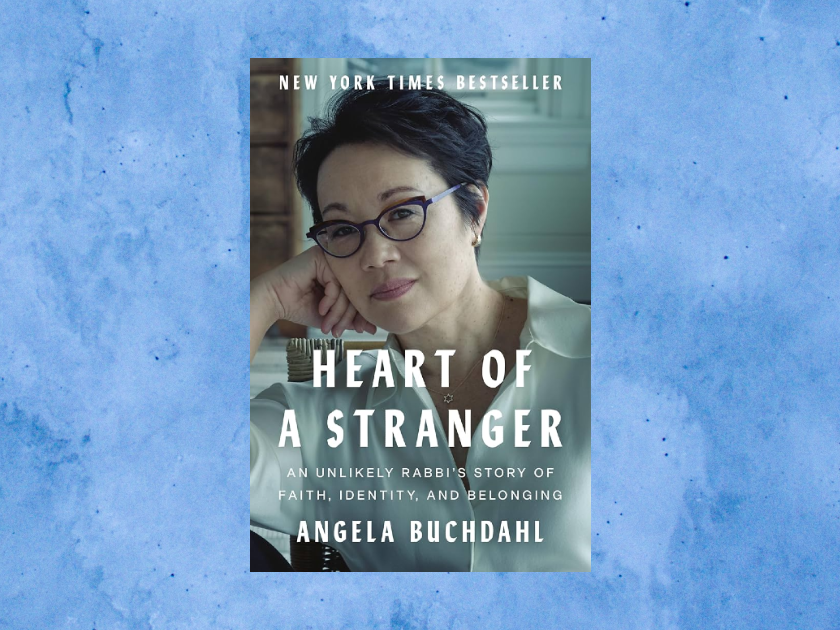

Rabbi Marc Katz spoke with Rabbi Angela Buchdahl about her groundbreaking new memoir, Heart of a Stranger: An Unlikely Rabbi’s Story of Faith, Identity, and Belonging. The rabbis spoke about the process of writing the book, Buchdahl’s journey to the rabbinate, and the stories and connection that have come from the book being out in the world.

Marc Katz: Let’s start with the obvious question. Why did you write the book?

Angela Buchdahl: I wrote the book because I wanted to share the wisdom and tradition of Judaism in an accessible way to both Jews and non-Jews alike. While I never saw my own personal story represented in literature when I was a kid growing up, I did see my story in the Torah. The Torah speaks to deep truths about the human experience, especially on relationships and family dynamics. It is the origin story of what it is to be a stranger, to be an Ivri, someone who is a boundary crosser. In the Torah’s teachings I could see myself, and it made me feel a little less alone, like I was part of this big, epic story. I wanted other people to find their way into this story too. So I pitched my book to the woman who became my agent and she said, “That’s nice, Angela, but I don’t think you’re gonna be able to sell that book. Maybe you could sell it to a Jewish press but if you want a mainstream publisher, that’s gonna be very hard to sell.”

MK: So that’s where the idea of writing a memoir came from?

AB: Exactly. What I was envisioning was writing a book on Jewish spiritual wisdom. Heart of a Stranger is something very different. My agent told me: “You’ve got this unlikely story. Why don’t you write a memoir, and then you can weave the spiritual teachings in.” When I started actually writing it, it took a month or two to figure out the current form. At first, I had chapters with meditations afterward, a very different voice. Then I made them more sermonic and made sure that they were thematically linked to the memoir material. It took a while to settle in on this form.

MK: I found it very artful, the way that you were able to pick a theme out of some element of your life — whether it was meeting your husband Jacob or figuring out that you loved music — and then find that right Jewish teaching to pair with it. How was it for you trying to pick out which element of your story would match with the right sermonic message?

AB: Well, you can probably relate to this as a rabbi. Sometimes you have an idea of what you want to say and you look for it in the text, and sometimes you open up the text and it speaks to you. Half of the sermons in the book, which are thirty-one in total, were repurposed from things I’d already written. So, I took some of my favorite themes from High Holiday Sermons, as well as from my set of weekly Meditations that I wrote for five years throughout the pandemic. I then tried to find the chapter where it matched. I had something written on hachnasat orchim (welcoming the guest), and realized it made sense to do it with the Jacob chapter. And sometimes, for maybe the other half of them, I thought to myself, here’s where I could do a teaching on X, and it kind of came out of that. In Judaism there’s the Torah portion, and then there’s the Haftarah, which is the more sermonic bits that are less narrative, but they’re thematically linked. Sometimes you can obviously tell why our tradition picked a Haftarah that goes with the Torah portion, and sometimes you’re like, “What’s the connection here?” It was not a scientific process. More art than science.

MK: Let’s talk about your title. There’s two pieces to your title that I want to talk about. First, I want to talk about your actual title, “Heart of a Stranger.” Tell me about that. Where did it come from? Why did you choose that as the title of your book?

AB: I had many different titles for this book. Originally, I was calling it Boundary Crossers. My agent suggested it should be Soul of a Stranger. I had talked about that theme a lot. It came out of the original introduction in which I talked about the story of Abraham and Sarah, one of the first stories that spoke such truth to me about not just my life, but about what it means to follow a calling of some kind to find your truest home; what it is to leave what is familiar and to go to someplace that’s very uncertain where you’re a stranger. That story is kind of the main thrust of the book. Soul of a Stranger was the working title for three and a half years. Nefesh Hager (soul of a stranger) is obviously not original to me; it’s from the Torah. But when it came time to actually decide on the title, my editor said “We’re not sold on soul. Soul is so religious.” And I said, “You know this is the memoir of a rabbi, right?” but they replied “I think it might be off-putting for some people. Why don’t you make it heart?” At the end of the day, what I’ve come to realize is that I’ve always had the heart of a stranger. Ultimately, I have found a sense of home and belonging in all these different communities and at the core of that feeling is love. So, I think there is a lot about heart in the book and I ended up feeling like it was absolutely the right title.

MK: Tell me about the “unlikely Rabbi” line in your subtitle. On the one hand, your story is very unlikely. You come from such a diverse background and your story shows that you could have gone in many different directions other than ending up being a rabbi. On the other hand, at this point, I think one in seven Jews is a Jew of color. So, you might be the first one to write a memoir about this, but you’re certainly not alone in having a diverse journey.

AB: Growing up as a kid in the 70s only 8% of children of interfaith marriage even identified as Jews at all. I was the beneficiary of Rabbi Alexander Schindler’s outreach sermon and his decision on patrilineal descent in 1978, which was soon after I arrived in America. Of my generation, it was even unusual that I saw myself as Jewish at all. I’m a Korean immigrant who has a Buddhist mother who did not convert. There were many pieces of this that made it unlikely, especially in the time. You are absolutely right that now, it’s much less of an unlikely story. Now, we can make a minyan of not just of Jews of color, but maybe even Asian-identified rabbis. That’s fantastic, I grew up most of my life feeling like the rabbinate was not a path that was in any way obvious to me.

MK: What do you hope people get out of this book and do you have an intended audience?

AB: My intended audience is everyone. I do not think this is only for a specific age or only a book for women. I think that this book is not only for Jews. I don’t even think it’s for people who are necessarily religious. One of the things that’s been interesting to me already, now doing this book tour and also starting to get notes from people who’ve read the book, is hearing from men and women, from Jews, converts, Jews of color, but also Jews with two Jewish parents, and the Catholic mother of my publicist who are all saying that the book resonated for one reason or another; from what it feels like sometimes to be an outsider, to seeking out meaning and purpose, goodness and kindness in the world at a time when it feels like there’s a lot of polarization and hate.

Someone who is my age said, “Wow, just being a woman and hearing your journey as a female professional trying to break the stained glass ceiling meant a lot.” The book addresses challenges that women face who are trying to do something that hasn’t been done by women before. There’s also a lot in there around what it is to be a rabbi in this moment of fighting antisemitism and dealing with the complexity of Israel. I also think there are Koreans who are reading this book, and there’s something about what it is to be an Asian person in America and the questions of identity for anyone who’s mixed race. So I think there’s multiple themes that are connected by all the different ways that human beings carry complex identities and the feeling that you don’t fit neatly in one place or another.

I think there’s multiple themes that are connected by all the different ways that human beings carry complex identities and the feeling that you don’t fit neatly in one place or another.

MK: Your book feels like a breath of fresh air. I would say the hot Jewish books over the past few years have primarily been about Israel and antisemitism, and your book finally is a hot Jewish book that is not about Israel and antisemitism, even if some of those themes appear throughout the book.

AB: Right. I actually didn’t have any of that when I sold it because all those chapters, Coleyville, October 7th, and beyond hadn’t happened to me. They hadn’t happened to us. And they weren’t a focal point of the book, but of course, you can’t have a rabbi’s memoir without grappling with those kinds of seminal events for our people, and what they mean.

MK: I’m curious, what would you change about the book if you wrote it today? I imagine that you wrote large chunks of the book before the real political heat about Israel started in the past few months. Would you change anything about the book knowing what our climate would be like at this moment?

AB: I really hope that this book is a little bit more timeless than that. Even the October 7th chapter was not so much about the aftermath, but about that particular moment in time and my first visit to Israel right after.There’s no way that I could keep the book up-to-date with all the ways that our community has responded. I’m fine with the fact that I kind of kept it to that moment.

MK: What’s your favorite chapter?

AB: It’s like asking your favorite child, but if I have to choose I might say that I think my last chapter is my favorite chapter. I called that chapter homecoming. On the one hand, it was a homecoming because it was coming home to my birthplace, Korea, with my daughter and my mother. But in some ways, what it really was emphasizing was that my true home is America. At the end of the chapter, I’m saying Kaddish at the gravesite of my grandparents.This American Jewish rabbi is saying this Jewish prayer in Aramaic for my Korean grandmother. That story wouldn’t even be possible if I hadn’t left my original home.

It’s not just that I begin and end the book in Korea. The story is resonant of Abraham’s story, that you have to leave your birthplace to find your truest home in some way, and that place, for me, is America. I couldn’t be who I am today if I had stayed in Korea. I had to leave.

I realized this when I wrote it but the first chapter of the book is actually about my mother’s spirituality and starts on a mountain. In my last chapter, I’m at the Buddhist temple with my mom and my daughter, and we’re at a mountain. Also my last chapter is a sermon on the idea of pardes, the idea of an orchard. My parents planted an orchard for their fiftieth anniversary, and we came out and we all saw it. And then I explicate the idea of the way we deconstruct text as the acronym of PARDES explains, explicating each layer of meaning. It’s interesting, because in the first chapter the parking lot at Mount Rainier is called Paradise, and I talk a little bit about how that mountain was sort of paradise. It’s subtle, and I bet most people will miss some of those ways that the first and last chapters bookended each other.

Rabbi Marc Katz is the Rabbi at Temple Ner Tamid in Bloomfield, NJ. He is author of the books Yochanan’s Gamble: Judaism’s Pragmatic Approach to Life (JPS) chosen as a finalist for the PROSE award and The Heart of Loneliness: How Jewish Wisdom Can Help You Cope and Find Comfort (Turner Publishing) which was chosen as a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award.