Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

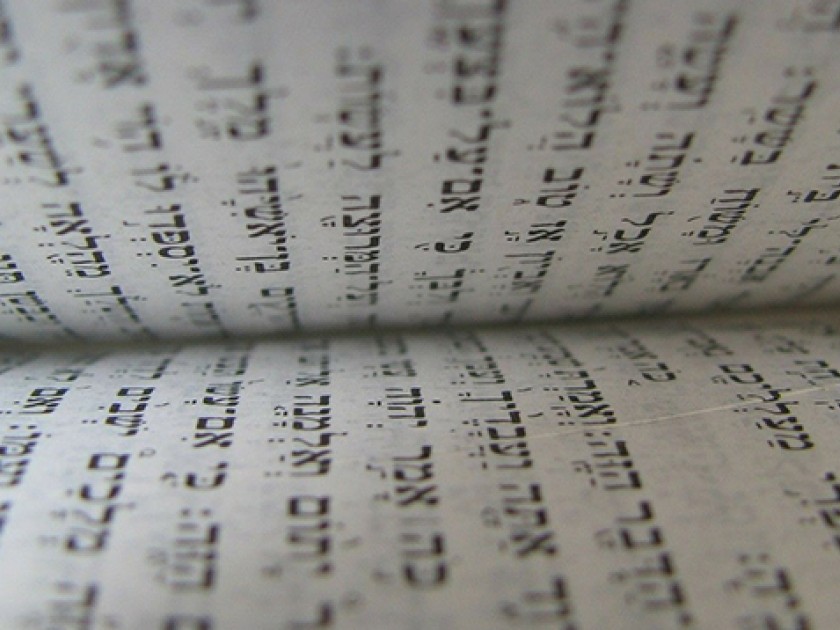

A story: The survivor of a global disaster, burdened by survivor’s guilt, drinks himself into a stupor. His youngest son comes upon him sprawled and naked on the floor. Rather than cover his father, he mocks him. The father is not completely unconscious; when he awakens, he remembers what his son did and is furious. “This is how you treat me? I’ve kept you alive, fed you, given you everything — and you do this?” He curses his son: “May you know grief from your own son, may he be a slave his whole life!”

This story might sound familiar. The father is Noah; the son, Ham; the setting, moments after the Flood has receded. And the story could have ended here, but for one thing.

A later biblical verse tells us that the accursed son’s son is the ancestor of the Ethiopians. And so it is that this story, first recounted in Genesis, became the source of the shameful Hamitic Myth, which states that Noah’s curse is the reason — a biblically-approved one — for the enslavement of black people from Ethiopia, and, by extension, elsewhere.

In the late 1800s, Southern preachers in the United States used this story to argue that slavery was God’s will and the natural order of things. Christian missionaries brought the tale with them on their travels to African countries. One such missionary, a Belgian preacher with a radio show, poisoned Rwandan society with the myth, turning Hutu against Tutsi (he used the myth to support his theory of eugenics, in which Tutsis were “closer to the white race” than Hutus). This led indirectly to the 1994 Rwandan genocide, when Hutu neighbors slaughtered between 650−800,000 of their Tutsi neighbors over several months.

When we studied this sequence of events — the Genesis story, the Belgian missionary, the radio show, the genocide — in Elie Wiesel’s class, I was distraught. How could the Bible, the urtext of my youth, the “portable homeland” of my people, be the cause, however indirect, of such horror?

How do we deal with disturbing and degrading religious texts? What do we do with textual interpretations that have caused so much harm? The question is difficult if you are a believer and cannot reject the sacred text entirely. It is much easier to argue that the texts were written by wrong-headed men in wrong-headed times, and that now, in our more enlightened age, we must relegate them to the realm of museums and curiosities. But for a believer, or a lover of sacred text, that is not an option.

Believers have two choices. They can accept the validity of even the most egregiously offensive ideas in their sacred canon, and live their lives and organize their collective policies accordingly. Or, they can engage with disciplined yet radically subversive hermeneutics. The first option was employed by Christian ministers in the southern states like Samuel How, who wrote in 1856:

Our second proof that slavery is the punishment of sin is drawn from Gen. 9:24, 25, where the sacred historian having mentioned the wickedness of Ham, the father of Canaan, says, ‘And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him. And he said, ‘Cursed be Canaan, a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.’ The term ‘servant of servants’, means a servant of the lowest and vilest kind.

A minister like How draws upon his Bible to create a world that accepts slavery. He takes the text at face value; his is a passive reading of the text, uninterested in wrestling with the conflict between text and life — or perhaps fully comfortable with the idea of slavery.

It is the other option which saved my faith.

In our weekly meeting, I asked Professor Wiesel about the terrible link between Genesis and Rwanda and the challenge of finding an ethical way to interpret holy books. “This is a problem the ancient rabbis already identified,” he said. “They taught that the Torah itself can be either an elixir of life or a poison, depending on how it is used. If it is made into a weapon, it is the worst weapon of all.”

“But if we prefer an interpretation, even for moral reasons, does that necessarily make it true? What if it contradicts the simple reading of the text? And if it is true to the text but is immoral, what are we to do?”

“If even the most authoritative teaching, the most sacred text, leads to dehumanization, to humiliation, to harm, then we must reject it. Remember, the Bible itself shows us how to do this: Abraham argues with God on behalf of Sodom. Moses breaks the tablets of law — yes, even the law must be broken when it threatens humanity. Job refuses to accept easy answers that falsely render him a sinner and God a vindictive god. We need courage in reading scripture, courage and compassion. Remember also: This is what the rabbis did with so many of the legends they taught, so many interpretations. They worked to align the text with their moral understanding. And in doing so, they gave us permission — no, an obligation — to do the same.”

Our discussion about Genesis and Rwanda continued, and I begin to understand his approach. When we encounter difficulties in the text, when we feel the distance between words on a page and our deepest moral intuitions, we allow the text to question us; perhaps our intuitions require refining. At the same time, we begin to challenge the text, to demand that it live up to our ethical instincts. When a text disappoints us with an anti-human message, we will avoid the sin of premature forgiveness, of letting the text off the hook too easily. A biblical verse seems to condone hatred? Well, it’s an old book, after all, from a different time, we might be tempted to think. But our role in reading sacred scripture is to ask two questions: “What does the text say?” and “Who may be harmed by this text?” In seeking an ethic of interpretation that remains true to the text and to our lives, we balance fidelity and conscience and attempt to make our religious traditions sources of blessing.

Adapted from WITNESS: Lessons from Elie Wiesel’s Classroom by Ariel Burger. Copyright © 2018 by Ariel Burger. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Ariel Burger is the author of Witness: Lessons from Elie Wiesel’s Classroom, which was an Indie Next List Pick, A Publishers Lunch Buzz Book, and which won the 2018 National Jewish Book Award in Biography. He is also an artist and teacher whose work integrates education, spirituality, the arts, and strategies for social change. An Orthodox rabbi, Ariel received his Ph.D. in Jewish Studies and Conflict Resolution under Elie Wiesel. A lifelong student of Professor Wiesel, Ariel served as his Teaching Fellow from 2003 – 2008, after which he directed education initiatives at Combined Jewish Philanthropies of Greater Boston. A Covenant Foundation grantee, Ariel develops cutting-edge arts and educational programming for adults, facilitates workshops for educators, consults to non-profits, and serves as scholar/artist-in-residence for institutions around the U.S. When Ariel’s not learning or teaching, he is creating music, art, and poetry. He lives outside of Boston with his family.