Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

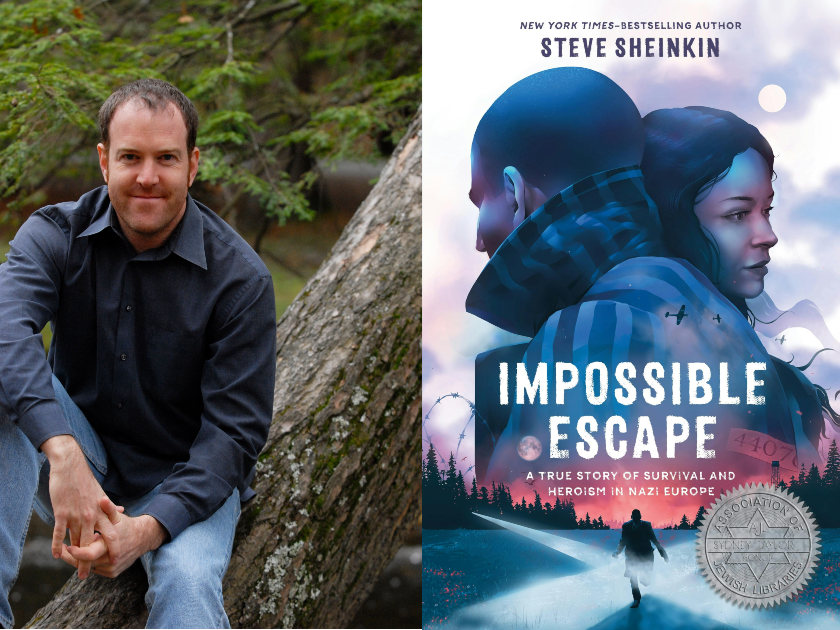

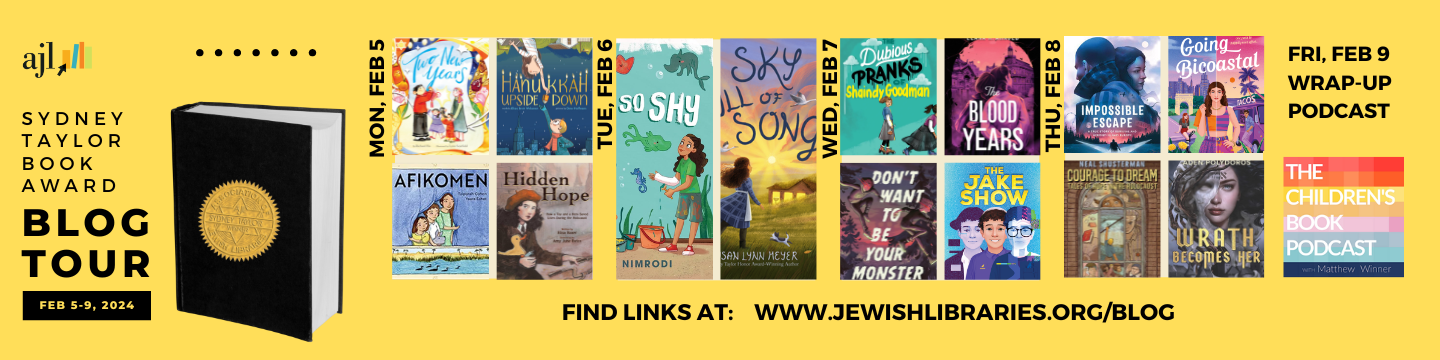

Steve Sheinkin is the author of numerous award-winning books for young readers. His latest book, Impossible Escape: A True Story of Survival and Heroism in Nazi Europe, was a 2024 Sydney Taylor Silver Medal winner in the Young Adult category. Emily Schneider speaks with Sheinkin about how he came to Rudolf Vrba’s incredible story of escaping Auschwitz and the author’s imperative to bring the story to as many young readers as possible. This interview is part of the Sydney Taylor Blog Award Tour. Find the full STBA blog tour schedule here.

Emily Schneider: Given the range of historical subjects you’ve written about in your many books, why, at this point in your career, did you decide to tell the story of Rudolf Vrba’s escape from Auschwitz?

Steve Sheinkin: I never thought specifically about doing a Holocaust book as one of my non-fiction books, but there was something about this story that always intrigued me. As a Jewish kid in Hebrew school and learning Jewish history, or from my dad, I never really knew this story; it would’ve intrigued and inspired me.

Later, when I started to read more in-depth about that time, it was maybe mentioned in a paragraph here and there. There was a teenager who escaped from Auschwitz. I thought, “Wait a minute, how do you not stop everything and tell me all about that?” But big books on a survey of the Holocaust can’t do that. They don’t have room.

The last time I was going through my notes looking for ideas, that one really jumped out at me. That was pre-pandemic, four or five years ago. I said, “Yeah, I really want to do that story.” I still didn’t know more than that there was a young Jewish guy who escaped and made this first eyewitness report. That was enough to start with. I said, “Yes, that’s the story I want to tell next.”

ES: So it wasn’t that you approached this by deciding to write about the Holocaust, but about a specific person’s story and why that was meaningful to you.

SS: That’s exactly right.

ES: Near the beginning of the book, I was struck right away by the scene where Rudolf is trying to cross the border from Czechoslovakia into Hungary. You write about Rudolf, “This was the first law he would break that night.” There was an inversion of values during that time, between the law and what was morally right. You must have felt it was important to establish how this Jewish teen has to go from being a rule follower to being a rule breaker.

SS: Yes, establishing the position that, in order to get to freedom, he needs to break the law. Even removing this despicable patch (the star of David) from his jacket is breaking the law, but he’s willing, and that is a hint that he’s willing to go much further. And in fact, he will. I’m also inspired by thrillers and the way people put together stories. Sometimes in non-fiction, you just can’t find out enough to create those kinds of high tension, high stakes scenes.

But in Rudi’s story, it’s all there. It has everything any storyteller would ever want. He’s leaving home. He’s going to do this. We don’t even know quite yet what he’s trying to do, but something very dangerous.

ES: You’ve mentioned being a storyteller. I wanted to ask about your literary style, which is one of the most outstanding reasons for the book’s impact. Some readers might see that as secondary to accuracy in a book about this subject. But your tone is important: dramatic, but never exaggerated. Did you consciously think about the type of language you would use?

SS: Definitely. I always think a lot about that. That comes entirely from my background and what I try to do. I grew up with my brother Ari making movies. That was our dream, to be a brother filmmaking team, and we pursued that through our twenties. It was one chapter of my life. Then I got a job writing history textbooks, which couldn’t be less cinematic: pure accuracy, everything backed up ten times; that’s the priority.

I realized eventually that I didn’t enjoy textbook writing because I couldn’t tell the stories. There’s just not room. Those textbooks are meant to be names, dates, facts, a reference. I wanted to get away from that. I still wanted accuracy, but I wanted to get back to the cinematic storytelling that made me want to be a writer. I’ve tried to combine those two things with Impossible Escape. I have tons of source notes in the back. I haven’t met a single kid yet who’s read them. They’re not very interested, but librarians are.

If you present history as names and dates, you’re going to lose just about everybody. It’s not just the content, but the way you present it that will impact whether or not it’s effective, whether or not people will pick it up and stay with it, and learn the stories that we’re trying to tell.

ES: You also weave in so much contextual material: restrictive American immigration laws, the ambivalent response of the press as evidence of the Holocaust started to emerge, the fact that Great Britain was reluctant to welcome Jewish refugees. You didn’t see these as digressions from the story.

SS: The book is for young adults. I needed to start with no assumptions. You shouldn’t have to know anything to read one of my books. The biggest challenge for writers, especially when writing for kids and young adults, is how to get in enough background information, but to do it seamlessly. Sometimes there’ll be a sidebar in a book, a shaded box, giving background information. I don’t like that as a reader; I want that seamless storytelling. I always write too much and then pare it down. You need to get the reader hooked on the story first, and then choose your spots to weave in that information – because it is interesting – just enough so that it doesn’t slow the story down.

ES: Chance was a key part of survival in the Holocaust. Maybe that seems obvious, but some readers are looking for a more redemptive message. That doesn’t diminish the value of individual qualities, like courage. There is a scene where Rudolf is working in the section of Auschwitz where items that were confiscated from murdered Jews and deemed useless are destroyed. He comes across an old atlas for children that includes a map of Poland, and that turns out to play a key role in his escape.

SS: Even as a very strong young man or woman, you needed luck. Rudolf was always determined to escape. He had already escaped from another camp, but he didn’t know exactly where he was. I find that detail really fascinating. He knew he was in Poland, but he was kind of a science kid, into chemistry, not geography. Kids today can relate to that. Maybe he wasn’t paying attention when they studied Central Europe in geography class.

The questions going through his head were, “If I ever get out of here, what do I look for? What landmarks? What are the cities and rivers I might see? What mountains? How far am I from the border?” It was just pure luck that he found the atlas, and this to me is the most cinematic of all the scenes in the whole book. When I read about it in the sources, it just leapt off the page fully formed.

There was luck, but also courage because he could have been killed for anything, or for nothing. He picked up the book, ripped out the page, and later – in the latrine– he took a quick look. He couldn’t keep it on him, so he memorized it. This was a brilliant young guy. He could do anything that he put his mind to. And in this moment, he realized, “Life or death, I have to memorize everything on this page.”

ES: Going from the peak of courage to the most brutal of human behavior, the Nazis in the book are not archetypes. They are individuals. They all subscribe to the same evil ideology, but you depict their individual personalities.

SS: It’s probably the hardest part of the whole story to understand. They all claimed to be human beings, although obviously they weren’t in some important way. This is what happens when people are taught hatred, when we start to separate people by religion or race and to rank them according to who deserves which level of rights. I did think that it was important not to show people as stereotypes, but as individuals who have a choice in what they do.

It was just pure luck that [Rudolf Vrba] found the atlas, and this to me is the most cinematic of all the scenes in the whole book. When I read about it in the sources, it just leapt off the page fully formed.

ES: The question of choice brings up perhaps the most painful topic of the Holocaust, the role of the Sonderkommandos–the Jewish inmates who were forced to participate in the murder of their fellow Jews. What did that mean for you in writing about that part of Rudolf’s story?

SS: I thought it was important. I knew there was a line, and I want my books to be accessible. I talked to Holocaust educators about what they tell students at what age. “When a seventh grader or a tenth grader comes into your class, what do you say about the gas chambers?” I took that advice to heart. We never would have heard from Rudolf and his friend, Alfred, who he escaped with, if they had ever been inside a gas chamber. But I wanted one of the figures in the story to be able to give an eyewitness account of what was seen there.

A few did survive being Sonderkommandos. Others wrote documents and eyewitness accounts that were found later, of what it was like to work in the most horrible of places. How did you get chosen, forced into doing this? How did you face that impossible decision of what to do? Some description of that was essential to the testimony that Vrba wanted to give later. At first I wrote too much, a scene that was just too graphic. The only way to find that line was to write, talk to experts, and then pull back to, hopefully, just the right line.

ES: In spite of the unrelieved horror in the book, heroism does keep surfacing. How did you try to achieve a balance between despair and some degree of hope, or just bearing witness?

SS: There are a lot of stories of people showing great courage, ones that kids don’t typically learn in the big picture of millions being killed. There were so many rebellions and actions, small and large. Rudi was always determined to escape. I also think that his motivation evolved, which I find fascinating, especially given how young he was.

I have a seventeen-year-old now, and it highlights just how young Rudi was when he got thrown into this situation. At first, he wants to live and escape, but the motivation quickly evolved from that into collecting information that he knew was not reaching the outside world. He had no way of knowing what the world knew, but he thought, “I want to be the one if no one else does it. I will tell the world what I’ve seen.” Then the bigger goal became, “Maybe if I do it in time, it can save some people who haven’t arrived yet. Because once they’re here, there’s nothing I can do to help them.” Rudi is, quite literally, driven by that hope. He is a heroic figure for that alone.

ES: Can you talk about the parallel story of the young woman who was Rudolf’s friend, later his first wife, Gerta Sidonová? Her experience was different from his during the war.

SS: Yes, Gerta’s story is also fascinating. It’s not the Auschwitz story. Certainly, most people didn’t survive that. Some people went into hiding. Everyone who did survive had a different story.

I thought the fact that Rudolf and Gerta were friends as kids, from a storytelling standpoint, was just too good not to use. She had a crush on him. He was a little bit older and didn’t see her in that way. They got separated by the war very early on. That invites the parallel story, a glimpse of another young Jewish person’s experience. The scenes at Auschwitz are so tense, frightening and dark. It’s effective for a storyteller to be able to cut – the way a movie would – to a different setting, a different storyline. Rudi had no way of knowing what was going on in World War II. Sometimes he would get glimpses from a newspaper or a bit of something that he would overhear from other prisoners who were just arriving. But Gerta was living most of this time under false names. She was able to listen to the radio, even to the BBC. It was very effective as a storytelling technique to be able to give updates through her point of view. They met again in 1944, in Slovakia. She was incredibly brave, working for the underground, helping other Jews get false documents, and he’s just escaped and is in hiding. Their reunion scene would seem too much if you made it up, but it’s not made up. It’s true. It’s what really happened.

Gerta lived right up until the start of the pandemic. I just missed talking to her. I got to know her daughter in London, and she documented her mother’s story really well.

ES: You’ve used cinematic terms again in describing the narrative. Another cinematic moment is in the epilogue, where you relate how Rudolf, in 1985, testified against a Holocaust denier in a Canadian courtroom.

SS: In my book, Rudolf’s story essentially ends when he’s twenty. He then joined the resistance. But he had an incredibly long and dramatic life. He became a scientist. He lived and worked all over the world as a chemist, but also always as a Holocaust educator and a witness. I wanted to point out that he never let anyone get away with telling lies. He saw it throughout his life. Unfortunately, it’s still happening. It may become more prevalent now that these witnesses aren’t going to be with us. I wanted to highlight that again, through something that really happened. A Holocaust denier in Canada was publishing ridiculous pamphlets about Hitler and denying the gas chambers. Some people said, “No, he’s just trying to get us to pay attention.” But others said, “The only way to counter this is with the truth, the light.” When the denier went on trial in Canada, Vrba wanted to testify.

Thankfully, for a writer of nonfiction, you can get the whole transcript, 3000 pages of testimony. And it was very cinematic; courtroom drama that you would expect in film. The Holocaust denier’s lawyer loved baiting survivors and questioning their stories, undermining them. Rudi would have none of that. They went back and forth in a very heated way. He had many, many parts to his experience in life, but one part of him was the fighter that would always tell this story, to fight the lies any way he could. I wanted to honor that in the epilogue.

ES: That epilogue leads me to my last question today. Some argue that books about the Holocaust disproportionally emphasize Jewish victimhood, at the expense of other parts of our history. Another perspective would be that now, as few survivors are left, the Holocaust is receding into the past, making it more plausible to deny or to downgrade in significance. What are your feelings about this issue?

SS: I thought a lot about it, too. I want to see a great diversity of books on the Jewish experience. The very first books I did that got published were comics of Jewish folk tales, The Adventures of Rabbi Harvey. They’re meant to be funny, joyful, full of wisdom and wit. But the story of Impossible Escape was also essential. It contains the context of the Holocaust and World War II, but it is really the story of young Jewish people, who I would say were heroes. (They would deny that, as they did in their lifetime.) I go to schools all the time. When I say, “This is a book about a Jewish teenager who escaped from a Nazi concentration camp,” not everybody knows what I’m talking about. I hoped to tell it in a way that would be compelling, that would be a page turner, that would make people want to read it, even if they don’t think they are interested. That’s why I worked so hard to try and make the story fast paced and have elements of good storytelling, of a thriller, because I want to win over those people who simply might not have otherwise been interested. As a lifetime collector of escape stories, I think it is the greatest escape story that I’ve ever found, not because I wrote it, but because it’s true. I felt that it was absolutely essential for me to tell.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.