Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

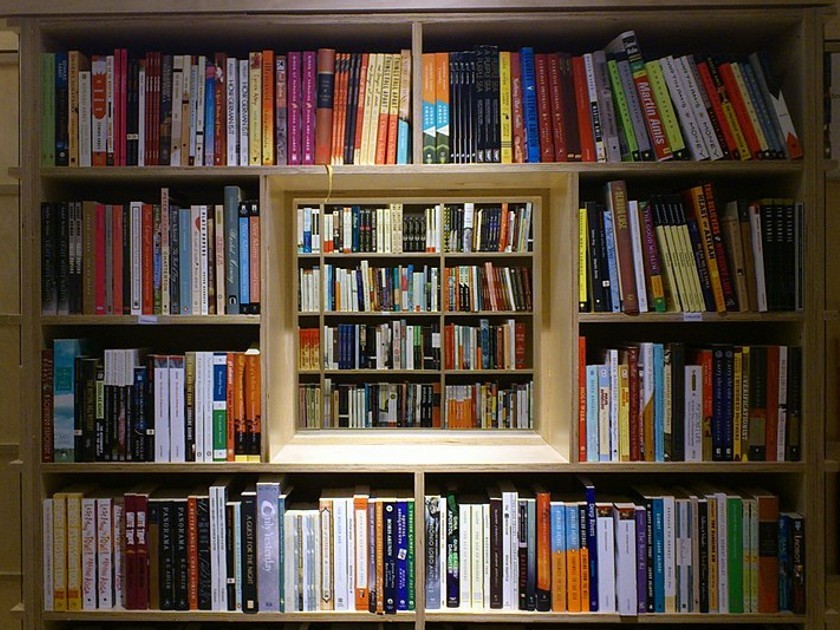

Seminary Co-op Bookstore, Chicago, Photo by Payton Chung, 2013

I first visited Chicago’s Seminary Co-op Bookstore when I was a confused and restless nineteen ‑year-old. It was there I found clarity, repose, and — although I didn’t know it then — my career.

Known as one of the finest bookstores in the world, the Seminary Co-op touted the motto, “no knickknacks, no coffee, just books.” The bookstore was a realization of a humble but powerful vision: a broad selection of books whose presence on the shelves created an undiluted browsing experience. The collection created a totalizing environment.

It was Judaism, a religion predicated upon books, from which I was attempting to take my leave. But even then, confused about many things and struggling to find my way, I knew that, whatever else I left behind, the presence of books should remain. Living a life among books is an especial privilege.

During an event at the Co-op, the Chicago poet Nate Marshall once said, that “the greatest thing a poet or poem can give you is permission.” A bookstore too, it turns out, can give you permission. That is precisely what that first descent into the Co-op established: permission to be among books outside of an institution of learning – be it a university or a yeshiva — and outside of a teleological paradigm.

I grew up in an Orthodox Jewish community in and around Brooklyn. The rooms of my childhood homes in Flatbush, Boro Park, and Elizabeth, New Jersey, were all book-lined; my yeshiva, my shul, my relatives’ homes, and the homes of my friends’ families were also laden with large books. The presence of books was a given.

From 1957 until 2012, my grandparents lived in a second-floor walkup apartment that they rented in Boro Park, on the corner of Sixteenth Avenue and Fifty-Third Street. My grandfather’s library — or rather, book-lined living room — made a particular impression. The bookcases were filled with books whose gravity was clear from the ornate, uniform spines. Ornate were these books, but not ornamental. The bookshelves always had gaps, and the gaps would move from week to week; an ever-rotating selection of volumes would be laid out on my grandfather’s book stand and desk.

Books and the landscapes they create are exceptional tools to cultivate our own interior landscape, which, after all, is our portable and permanent homeland.

These books were read — books are for use, after all — and were treated with reverence and love. Observant Jews are accustomed to kissing the cover of a book after closing it — a habit that has remained with me throughout the years. Along with the British literatus Leigh Hunt, who, in effusing about books, wrote of how he liked to lean his head against them, followers of my given tradition might say, “When I speak of being in contact with my books, I mean it literally.”

These books were read in groups called chevrusas, a Hebrew word whose root means “friend.” When I was a young boy, I would join my grandfather’s chevrusa on occasion, just to observe. Seated on an austere bench in the basement of the shul across the street, my head barely clearing the tabletop, I sat with large men and their large Aramaic books watching them question, ponder, argue with, and delight in what they found on those pages.

Following my grandfather’s model — books aren’t ornaments — and knowing that there were treasures to be found within the volumes, I quickly became fearless in dislodging shades. As my intellectual life was developed in the interstices between the yeshiva and the academy, the justification of the existence of a bookstore like the Seminary Co-op was self-evident. This was the place where one could become learned — a talmid chacham—and fashion a daily practice that would lead one through a more meaningful life.

The Jews are a people who are raised to question — interrogate even — their god. They do so through commentary primarily, not criticism. Their libraries (like my grandfather’s), composed of volumes of loving expansion of their canon, might be all they’ll ever know as home. After all, they are fated to wander — a rootless people who are perennial strangers in strange lands. Without a homeland, the Jewish people made the book their homeland.

Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentine writer and librarian, was a reader first. The critic Elizabeth Hardwick wrote, for Borges “the library is the landscape of human drama; it is experience, tragedy, social history.” As Jews made their homeland a book, so Borges and I made the library and the bookstore, respectively, a homeland. And perhaps the imagined book that might best represent our homeland, as the Talmud represents the homeland of Jews, is the catalog of catalogs.

In some way, we are all wandering people, searching for community, searching for ourselves. Books and the landscapes they create — both as objects and as mechanisms to deliver the hopes, dreams, moods, principles, and wisdom contained between their covers — are exceptional tools to cultivate our own interior landscape, which, after all, is our portable and permanent homeland.

In Praise of Good Bookstores by Jeff Deutsch, out April 5 2022

Jeff Deutsch is the director of Chicago’s Seminary Co-op Bookstores, which in 2019 he helped incorporate as the first not-for-profit bookstore whose mission is bookselling. He lives in Chicago.