Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Signs located at the cemetery in Moisés Ville, Photo courtesy of the author

“Murder of a young girl. Mystery around it — Public consternation ”: the news appeared on Tuesday, July 17, 1906, in the Buenos Aires newspaper La Nación. It had arrived by telegraph from the correspondent in the province of Santa Fe — some 400 miles to the north — and said that among some tall reeds, near a train station, the body of a nineteen-year-old girl had been found. Her name was Miriam Aliksenitzer at the time of leaving the czarist empire with her family, but was changed to María Alexenicer a few months later on her entry papers to Argentina. The colony of Moisés Ville was a small agricultural town founded in 1889 by Russian Jewish immigrants that, over the decades, would become the “Jerusalem of South America.” Suddenly Moisés Ville was the scene of a shocking murder that would be in the pages of the national newspapers for two months, inundating the police chief of the area – an old soldier named Golpe Ramos – with accusations of possible culprits.

But the murder of Miriam Aliksenitzer was not the first homicide in Moisés Ville. Much later, in 1947, an elderly journalist wrote an account of twenty-two murders that had shaken the colony in those early years at the turn of the century. Most of these murders were tied to robberies in rural areas committed by gaucho bandits; however, some of the others were not motivated by theft, as it seems to be the case with Miriam Aliksenitzer. She was most likely murdered in the course of a rape.

In addition to greed-fueled theft, there was a certain element of xenophobic hatred at play. It was not a novel concept that immigrants could generate resentment among the locals, shown by the events of 1872, when some fifty gauchos attacked the town of Tandil (in the Province of Buenos Aires) under cries of “Death to gringos!” Thirty-six immigrants were massacred. The tragedy was instigated by a mysterious witch doctor who died not long after in prison.

“The First Jewish Victims in Moisés Ville” was the title of that 1947 record of twenty-two murders, published in a yearbook of the Jewish Research Institute (known by its Yiddish acronym IWO, the — organization still exists and is dedicated to the study of Jewish-Argentine culture). The author of the article was Mijl Hacohen Sinay, and he had spent some years in Moisés Ville before 1900 although by 1947 he no longer lived there.

I know his story well: Mijl Hacohen Sinay was my great-grandfather.

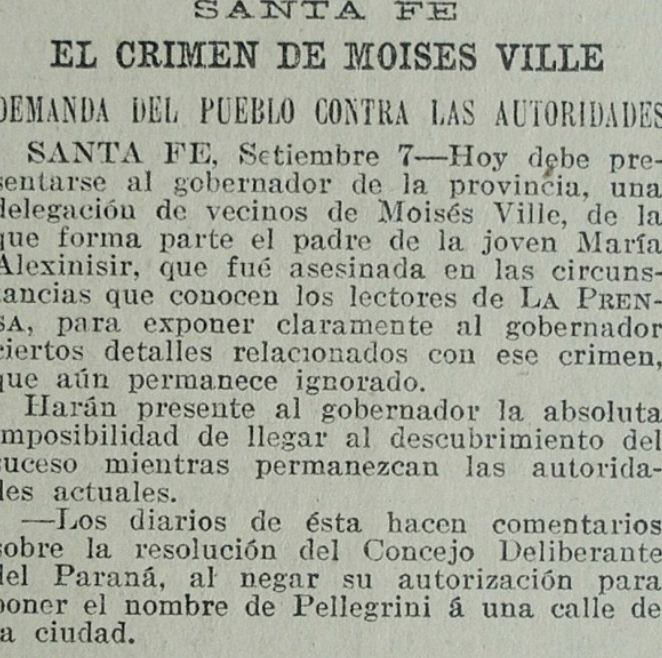

La Prensa, Sept. 7, 1906. Titles: “Santa Fe — The crime of Moisés Ville — Demand of the people against the authorities” / Archive: Biblioteca Tornquist-BCRA

When I came across the article and the story of the crimes, I went on a quest to learn more. I discovered that the body of that murdered girl had been kept for more than a hundred years in a square and heavy grave in the Moisés Ville cemetery, which was the first Jewish cemetery in Argentina. Despite the weather and the wind, you could still read the Hebrew inscription on her tombstone:

“Here lies / the young maiden / Miriam daughter of Zalmen / Aliksenitzer / who was killed at the hands of / monstrous people on the eve of / the 23rd day of the month of Tammuz / in the year 5666. May her soul be bound up in the chain of life.”

Several months before standing in front of that grave, I had discovered my great-grandfather’s article by chance. It was my father who found it online and emailed it to me. We did not know then that something important had begun.

Four years after that email, sixty-six years after the publication of the original article by Mijl Hacohen Sinay, and one-hundred-twenty-four years after the first homicide recounted in that article (one that took place in 1889, even before the colony had a name), my own investigation into those murders was turned into a book (Los crímenes de Moisés Ville, 2013, Tusquets) and is now published in English by Restless Books: The Murders of Moisés Ville: The Rise and Fall of the Jerusalem of South America.

I took as a starting point for my research the text of Mijl Hacohen Sinay, who narrated the twenty-two homicides. With my background in criminal and investigative journalism, I’ve met lawyers who love fame, criminals who defend themselves in the media rather than in the court of law, and I got used to police officers who tell short versions of the truth so as not to explain too much. However, when faced with the murders of Moisés Ville, I wondered how best to approach the investigation of these events that had occurred in such a distant time, in such a strange space.

The investigation was composed around several axes: the familial accounts of the descendants of the victims, the stories of the current inhabitants of Moisés Ville (still loaded with centuries-old clues); the historiographic works of the region, the press reports from the late nineteenth century that told the events first-hand, and the accounts of other settlers who —like my great-grandfather— had left their own testimonies (which I found at the IWO Institute, thanks to the work of hundreds of volunteers who had rescued these books from among the rubble of a terrorist attack in 1994). Many of these accounts were in Yiddish.

Crime can be an excuse for telling a bigger story.

All of these elements contributed to my search, with the notable exception of the court records: the official accounts of these murders don’t exist. I searched for them in the General Archive of the Courts of the Judicial Power of the Province of Santa Fe, in the General Archive of the Province of Santa Fe, in the departmental offices of San Cristóbal, in the Rosario museums, but nobody knows what happened to those papers. The court documentation of crimes ends abruptly in 1888, just a year before the first murder in Moisés Ville. From there onward, and until 1915, very few records are kept. The mysteries of bureaucracy. “Our problem is always space,” the director of one of those archives admitted to me, and she explained that the documents require a building infrastructure that is not usually prioritized in public agendas.

Crime can be an excuse for telling a bigger story. That is why in this book I am interested in showing these cultures through the specific people involved in these murders. A lot of my sources describe the lives of the victims, but that of the criminals is hidden. Why? The press of that time was not interested in preserving the names of these murderers, who were townspeople and in most cases illiterate and who, therefore, could not represent themselves through their own writings.

I could only find the names of the killers in three cases; for example, a gaucho named Coria (it’s a surname). In his book Di Yuden in Argentine (The Jews in Argentina), published in 1914 and notably the first work about the local Jewish community, David Goldman (son of the rabbi who founded Moisés Ville) wrote:

“Especially feared was that famous bandit of the time, Coria, or, as he was often called, ‘Coria mit di matikes’ (Coria with the mattocks). He was big boned, naturally strong. His presence alone instilled fear in all. He had twelve children, all of them murderers. And wherever a tragedy might strike it was known that they had been involved.”

David Goldman mentions him immediately after detailing a few murders in Moisés Ville. Later, I learned of another Coria, first name Federico, who on February 19, 1902, was sentenced by a court “to a penalty of imprisonment for an unspecified term” for having caused the death of one man. This, nothing more, is what appears in a brief, two-page dossier held at the General Archive of the Province of Santa Fe. Is Federico Coria the same ‘Coria mit di matikes’? Sources weren’t able to confirm it.

And I understood, as I proceeded to reconstruct each of the twenty-two homicides that, despite the fact that the court records have been lost, and that a century has passed, these stories still hold some strong significance in the present.

In Yiddish culture there is a concept, “di Goldene Keit,” the golden chain, that refers to the chain of generations and the moral obligation to bequeath, from father to son, all knowledge. No one is the sole owner of the truth. Each generation is the custodian of it for the short time in which we pass through the world, so we must leave it to the next generation as comprehensively as possible. We are free to adapt our opinions, but we need to have enough material to choose from.

Bringing this series of homicides forward from the mists of time is a way of adding something to that chain of generations, and understanding how that first friction between gauchos and immigrants later fused into a new, resilient identity for a new time.

The case of Miriam Aliksenitzer went unpunished.

Javier Sinay is a writer and journalist. His books include Camino al Este, Cuba Stone (in collaboration), Los crimes de Moisés Ville (forthcoming from Restless Books as The Murders of Moises Ville, 2022), and Sangre joven, which won the Premio Rodolfo Walsh de la Semana Negra de Gijón, España. In 2015 he won the Premio de la Fundación Gabo/FNPI for his chronicle “Fast. Furious. Dead.,” published in Rolling Stone. His work has appeared in the newspapers La Nación and Clarín, in Buenos Aires, and on the website RED/ACCIÓN. He was also a South America correspondent for El Universal (Mexico) and the editor of Rolling Stone (Argentina). He has collaborated with Gatopardo (Mexico), Label Negra (Peru), Letras Libres (Mexico) and Reportagen (Switzerland). He lives in Buenos Aires.