Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

In today’s installment of the Visiting Scribe for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning, Eddy Portnoy sat down with Ben Katchor to discuss his newest book, Hand-Drying in America: And Other Stories, which will be published by Pantheon Books on March 5th.

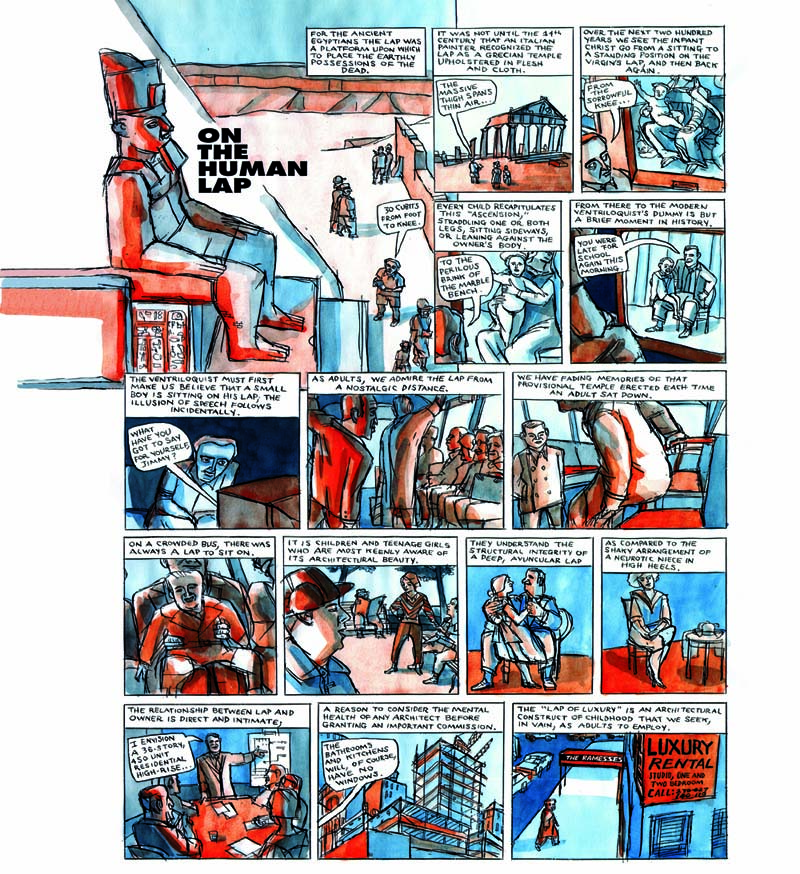

The artist Ben Katchor is a master of a visual urban milieu that echoes post-war New York City, but really isn’t that at all. Populated by stocky characters who tramp about and explore an oddly familiar, yet completely invented universe, Katchor’s picture-stories (as he likes to call them) are stirring forays into the urban absurd. The recipient of Guggenheim and MacArthur awards, among others, Katchor creates a kind of visual poetry comprised of everyday artifacts and activities. His ability to bring everyday objects and activities to the forefront of his visual narratives lends his work an imaginative, absurdist quality fired by light switches, peepholes, wheelchair ramps, coat check rooms and invented occupations, like spittoon pump engineers and rhumba line organizers. Katchor sees what we don’t in pedestrian objects and events and crafts short, comic narratives out of them. His books, which include Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer; The Jew of New York, and The Cardboard Valise, are part of his continually expanding oeuvre, which has come to include operas based on a number of his stories.

The artist Ben Katchor is a master of a visual urban milieu that echoes post-war New York City, but really isn’t that at all. Populated by stocky characters who tramp about and explore an oddly familiar, yet completely invented universe, Katchor’s picture-stories (as he likes to call them) are stirring forays into the urban absurd. The recipient of Guggenheim and MacArthur awards, among others, Katchor creates a kind of visual poetry comprised of everyday artifacts and activities. His ability to bring everyday objects and activities to the forefront of his visual narratives lends his work an imaginative, absurdist quality fired by light switches, peepholes, wheelchair ramps, coat check rooms and invented occupations, like spittoon pump engineers and rhumba line organizers. Katchor sees what we don’t in pedestrian objects and events and crafts short, comic narratives out of them. His books, which include Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer; The Jew of New York, and The Cardboard Valise, are part of his continually expanding oeuvre, which has come to include operas based on a number of his stories.

His most recent publication, Hand-Drying in America, is a compilation of full-color, one-page picture stories that appeared in the urban design and architecture magazine, Metropolis. Like most of his work, they take place in an invented Katchoresque urban world. I sat down with Ben recently to have a meandering discussion about it.

Eddy Portnoy: Your stories are full of unusual names of people and places, are any of them real?

Ben Katchor: It’s strange when someone tells you that you’ve made a literary, or cultural, reference in a strip to someone you’ve never heard of. It’s something I made up, but then they say that’s the famous Israeli comedian. Somebody wrote a whole thesis centered around the connection between the character, Kishon, in The Jew of New York, and the Israeli writer, Ephraim Kishon, who I had never heard of. I just like the sound of the name, like a cushion or a pillow (in Yiddish). Some, like Harkavy, in The Slug Bearers of Kayrol Island, are real references (in this case, to Yiddish author, Alexander Harkavy).

EP: Jewish names and references sometimes pop up in your work. Is there a Jewish component to this book?

BK: Well, only that the the author had parents who grew up in a more traditional, early twentieth century Jewish culture.

EP: Is that reflected in the book? Some of your works have Yiddish references. Are there any here?

BK: I don’t know. A lot of Yiddish words have come into English. I just wanted more to come. It’s a way to introduce new Yiddish words into the English language. Not that I define them, but…well, maybe there’s nothing Jewish anymore in the world.

EP: I think there probably is.

BK: I don’t know. I think it’s a pretty nebulous term. Even historically.

EP: What role did Yiddish play when you were growing up?

BK: It was my father’s language. We lived in Bed-Stuy and most of his friends were Yiddish speakers. There were always Yiddish papers, like the Freiheit in the house. He took me to all these Yiddish cultural events, concerts, lectures, plays, all before the first grade. Those years were a whole life, an eternity. That’s a long time for a little kid, all these incredible events. He would drag me along on errands to the Lower East Side, I used to like to go along. He wanted me to be able to function in Yiddish, but not so much that he forced me to study it. I didn’t really use it, I always spoke English.

EP: Was it a religious household?

BK: No, my father had no interest in organized religion. He was an atheist, a utopian socialist who subscribed to the Freiheit, the Yiddish-language Communist daily paper.

EP: So it was just the secular cultural Jewishness.

BK: Just!? Maybe that’s all there is to it. I think that was an enormous world of cultural activity. I could hear all this Yiddish music, I grew up listening to Yiddish records and we had a library of Yiddish books, and we told jokes from the humor column in the Freiheit.

EP: What role does the city you grew up in play in your work?

BK: Well, Knipl takes place in an imaginary large East Coast city. It may be filled with Jews, but also disciples of a countless cultures and religions of my own invention … I guess you could analyze the source of these things in the real world and determine that they could only have been invented by someone who grew up in New York urban circa 1950 to the 1970s. There’s an old Knipl strip about a guy playing with the elastic band of his underpants who lives in a union housing project. A good historian could look at that and figure out exactly which union in New York inspired that story. He could analyze the brands of men’s underwear available during that period, the hair patterns on the character’s body as a sign of a particular ethnicity, and so on. You could probably go into every one of these stories and analyze the details asking, what did Katchor know, what could Katchor know, growing up and how is that unique to his socio-cultural background or milieu. In such an exercise the chances of error are great.

My strips reflect a particular kind of dislocated urban environment. And maybe in a hundred years, you’ll have to annotate these things. After they get rid of all the unions, they’ll say, “what do you mean, ‘The Men’s Underpants Union.’ What does that mean, a ‘union?’” EP: But a lot of it is also invented.

EP: But a lot of it is also invented.

BK: The kinds of things that have never been recorded in history have to be made up. History only records very narrow slices of what goes on in the world. Nobody wrote about the guy who came to Mordecai Noah’s Ararat and was disappointed by the failed scheme. That’s what inspired me to write and draw The Jew of New York. It’s so-called historical fiction.

EP: Would you like to conclude by saying something about Hand-Drying in America?

BK: It’s a compilation of fifteen years of short stories about the built world. As I’ve lived all my life in cities, I can’t help but try to find some sense in the way things have been arranged. It’s a form of appreciation for a failed world.

An expert on Jewish popular culture Eddy Portnoy has an MA in Yiddish from Columbia and a PhD in Jewish history from JTS. The exhibitions he has created for YIVO have won plaudits from The New York Times VICE The Forward and others.