Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

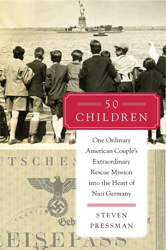

Holocaust Remembrance Day emphasizes the response of Americans to near-annihilation of the Jews in Europe. A recently published book by Steven Pressman, 50 Children: One Ordinary American Couple’s Extraordinary Rescue Mission into the Heart of Nazi Germany (Harper), is a gripping story. The author superbly intertwines the events of the Nazi tyranny toward the Jews with the theme of hope, showing how two Jewish Americans, Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus, took up their call to duty, as they became involved with rescuing refugees in 1939. Elise Cooper recently spoke to Steven Pressman about his work.

Holocaust Remembrance Day emphasizes the response of Americans to near-annihilation of the Jews in Europe. A recently published book by Steven Pressman, 50 Children: One Ordinary American Couple’s Extraordinary Rescue Mission into the Heart of Nazi Germany (Harper), is a gripping story. The author superbly intertwines the events of the Nazi tyranny toward the Jews with the theme of hope, showing how two Jewish Americans, Gilbert and Eleanor Kraus, took up their call to duty, as they became involved with rescuing refugees in 1939. Elise Cooper recently spoke to Steven Pressman about his work.

Elise Cooper: Do you agree that this book is about Jews actively participating in helping?

Steven Pressman: One of my friends, Paul Shapiro, who works for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, says that this story punctuates punctures one of those myths: the submissiveness of the Jews. There were Jewish groups and leaders trying to save lives but they ran up against incredible obstacles, particularly the U.S. immigration laws.

EC: Can you briefly describe the obstacles the Krauses faced, the first being the State Department?

SP: Gil’s toughest obstacle was not the Gestapo in Berlin or Vienna, but the U.S. State Department. It was tougher for Gil to get the children into the U.S. than it was to get them out of Nazi Germany. It is a minor miracle that he was able to work within the system and figure out a way to get visas for those fifty children. He had to overcome high-level State Department officials, like Breckinridge Long, who were openly anti-Semitic, had no sympathy for the plight of the Jews, and put up brick walls. I discuss the arguments, coming out of the Depression, about immigrants taking away American jobs. What about the children? A ten-year-old is not going to take away a job. FDR was not going to go to war to save Jews. He knew that public opinion polls showed that 95% of the American public were against liberalizing the immigration laws. I think in reading this story Americans should be reminded that this country fell short. People should remember that during this period the Nazis wanted the Jews to leave, although they were only able to leave with the shirts on their back.

EC: What about the other obstacles within the U.S.?

SP: The Krauses had to deal with their fellow American Jews. For some it was pure jealousy and for the organizations there were turf wars. Yet, for others it was the constant fear of backlash and anti-Semitism that Jews had to live with, even in America. The book has a telling public opinion poll: while 95% of the America public was against liberalizing the immigration laws a more striking statistic is that 25% of American Jews also did not want to increase immigration.

EC: Can you describe the obstacles they faced in Nazi Germany?

SP: In Austria there were banners and storm troopers everywhere. There were signs in almost all the shops that said ‘Jews are forbidden here.’ They knew as Jews they were in the belly of the beast. They literally had to sit across the desk from a Gestapo officer explaining how they planned on taking the fifty Jewish children to America.

EC: How would you describe Gil?

SP: He was a very smart, savvy, determined, and stubborn guy. My wife, his granddaughter, says he was the ultimate contrarian. If someone would say ‘up’ he would say ‘down.’ One of my biggest regrets, since they already passed away, is that I could not sit down with them and ask what went through their minds.

EC: Can you discuss how the children were chosen?

SP: They chose those they felt would be emotionally and physically the strongest. The average age was between eight and eleven years, with only a few teenagers. A powerful scene in the book is when five-year-old Heinrich Steinberger was taken off the list after becoming ill shortly before the departure from Vienna. He died three years later at the Sobibor death camp. His picture is ingrained in my mind. I had an email relationship with the wife of the person who took his place. Just think how these two lives had changed. Gil was only limited to fifty because of the amount of housing they had back in Philadelphia. Unfortunately, at that time no one anticipated that leaving any of these children behind meant they would die.

EC: What about the parents’ reactions?

SP: These two secular Jews took action at a time when it was still possible to save lives. They left their own two children at home while risking danger by entering Nazi Germany to save the lives of children they did not know. Most of the parents felt they had no choice. Eleanor wrote that the mothers appeared more hopeful than the fathers, perhaps because the men already had their businesses and livelihoods taken away from them and they now had to lose their children as well. I could not even fathom [considering] such a situation.

EC: Do you think your book relates to today?

SP: This is written seventy-five years after the Holocaust, and hopefully will serve as a reminder of what happened and a warning of what can still happen. There are recent reports of Jews in the Ukraine having to register, pay a tax, and disclose their property. My first reaction was how could this be happening in the twenty-first century? How is this possible? It’s chilling to read these reports and took me back to 1939 Vienna, the setting for my book.”

EC: Numbers are significant in the Holocaust. Do you agree?

SP: We are immersed in numbers. Six million died, 1.5 million of them children. Yet, even though fifty is such a small number in comparison, it is a number people can grasp.

This was the single largest group of unaccompanied children brought to America. Yet, the number is actually much larger than fifty if people take into account that those children lived to have children and grandchildren.

EC: Since the book is based on the HBO documentary 50 Children: The Rescue Mission of Mr. and Mrs. Kraus are there any differences?

SP: I decided to make the film first because I saw it as a new challenge. Even though the book focuses on the same story it is much more multilayered and in-depth than the film. The book richly and fully explores the broader historical context, the lives of Gil and Eleanor, and the details of the rescue.

SP: I decided to make the film first because I saw it as a new challenge. Even though the book focuses on the same story it is much more multilayered and in-depth than the film. The book richly and fully explores the broader historical context, the lives of Gil and Eleanor, and the details of the rescue.

EC: What do you want readers to get out of the book?

SP: I hope this small story of the Holocaust reminds people of the broader picture. We are within about ten years when there will be no actual eyewitnesses left. I also think it transcends the Holocaust since it shows that individuals can do extraordinary deeds. As a Jew I feel somewhat fulfilled that I was able to write the movie and this book about the Holocaust.

Elise Cooper lives in Los Angeles and has written numerous national security articles supporting Israel. She writes book reviews and Q and A’s for many different outlets including the Military Press. She has had the pleasure to interview bestselling authors from many different genres.

Related Content: