Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

There are risks, I have come to learn, when a Boston lawyer writes a novel about a desperately lonely, romantically awkward, Boston lawyer who seeks lasting love. In an Asian brothel. Who can say, after all, what the contours of anyone’s inner life may be? It wasn’t curative, I learned, when my wife would insist at every instance that The Double Life of Alfred Buber was a novel, not a diary.

There are risks, I have come to learn, when a Boston lawyer writes a novel about a desperately lonely, romantically awkward, Boston lawyer who seeks lasting love. In an Asian brothel. Who can say, after all, what the contours of anyone’s inner life may be? It wasn’t curative, I learned, when my wife would insist at every instance that The Double Life of Alfred Buber was a novel, not a diary.

I wasn’t lonely when I was writing this novel, or even, I hope, romantically awkward, but I was bored practicing law in Boston. I linked up with an old friend who’d been indulging his wanderlust for years and was in Rangoon trying to set up a law practice. I ended up doing several spells in his office, and there in Rangoon — at the American Club and elsewhere — and in Bangkok where we’d go on weekends, I saw up close the legions of Occidental Adams and their young Oriental Eves, and I began to wonder at it. There is sex involved, for sure, and money too, but there’s often far more to it than that: There are illusions, dreams, some happiness that isn’t entirely transient. We called marrying and making permanent the liaisons we saw around us “making the ultimate Mistake.”

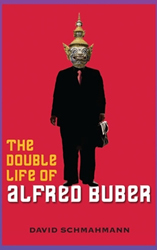

Buber was born in my study late at night, my wife and kids asleep upstairs, out of that novelist question: “What if?” What if, indeed, your personal shortcomings meant that your life was devoid of beauty and love, and illusion? What if you abandoned your deepest scruples intent on finding those things, and then, regardless of how base the origins of the quest, cleansing them, cleansing yourself, and transforming them into something wholesome. Not saving the poor little prostitute. Saving yourself. Aren’t we all fundamentally the same, in the end, men and women, old and young, rich and poor, in what we want and need? Is it so laughable a whim to believe it? My Buber with his bulbous face, occasional yiddishisms, Victorian sensibilities, is no satyr, and yet his compulsions draw him into the cauldron; and if his illusions are Henry Higgins, he isn’t the first to delude himself. He won’t be the last.

And then, perhaps, he does, against all the odds, stumble upon a chance at happiness. Even as he marvels at his pluck, he excoriates himself for his foolishness, for the sheer ickiness of it all, and then flounders. He loses his sense of what is real and what is not, and almost inexorably his two lives collide in a way that leaves no room for illusion.

Buber’s obsession has been compared to Humbert Humbert’s – the comparison is affirmed by some, rejected by others: it was never mine – and it’s won awards too. Either way, in the end I don’t much care any more about the risks of being seen as my character.

He’s as decent a heartbroken man as you’ll find.