Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

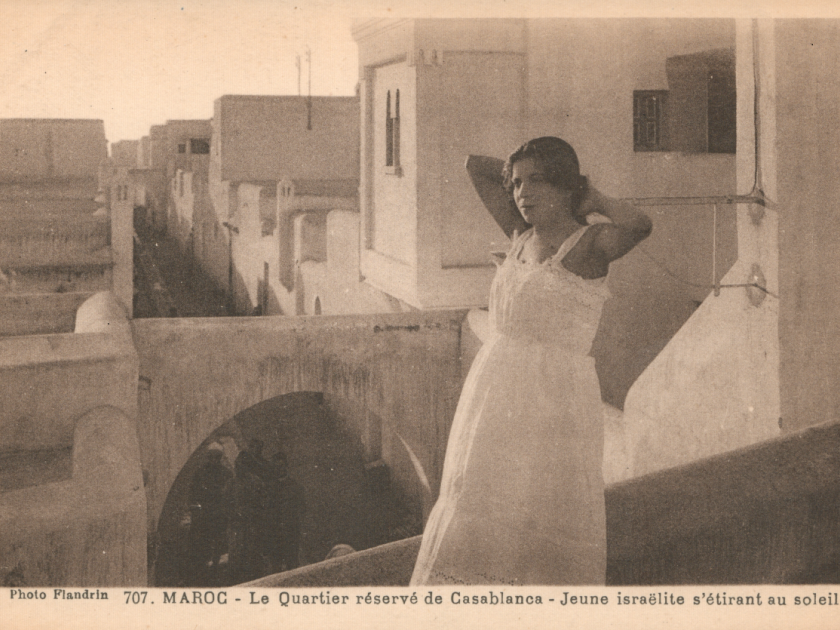

“The reserve district of Casablanca young Jewish woman stretching in the sun.” Photo courtesy of the author

I doubt I would have had the courage to put this book together on my own initiative and must confess that there were times when I was more inclined to curse the publisher who brought me in on this project rather than thank him for letting me make it truly my own. A book like Jews in Old Postcards and Prints obviously cannot offer anything even approximating comprehensive coverage of Jewish life and culture in Europe, the Yishuv (Eretz Yisrael/Palestine), and North Africa in the era that is its principal focus, the “golden age” of the postcard (the late 1800s and first half of the 1900s). Putting it together involved an endless succession of often difficult and occasionally painful choices; it is no exaggeration to say that for every image that has gone into the book, at least one other image had to be excluded. The companion volumes we are currently preparing will offer some relief in this respect and give readers who want to know more about Jewish life in specific regions access to additional material.

It is far from unusual, of course, for authors to want to put more into any given publication than is possible. However, most of what these images show was wiped out by the Shoah and the expulsion of Jews from North Africa, making the choice between them a particularly sensitive issue. These images were produced, published, and circulated without knowledge of the looming catastrophe. Yet neither would it be legitimate to present this material and the vibrant Jewish life and culture it reflects as though the subsequent destruction had not occurred. Trying to strike the right balance in this respect has been a profound and enduring challenge.

It would be misleading, however, to suggest that the principal difficulty in putting together this book lay in the embarrassment of riches it faced. While some aspects of Jewish life and culture are covered extensively by readily available old postcards and prints, many others are not. This is due in part to the nature of postcards and prints as media. It is worth considering the various hurdles postcards or prints have had to take to make it into this book. Someone needs to have thought the motif in question worth drawing or photographing in the first place. At the risk of stating the overly obvious, in the case of photographs, somebody capable of making the photograph needs to have been in the right place at the right time with the right equipment. In the second instance, somebody needs to have thought the motif worth circulating, a decision presumably predicated on the assumption that it would be of interest to a significant number of potential customers. In the third instance, the postcard or print needs to have been acquired and then considered worth keeping. Alternatively, it may have sold particularly badly and was therefore stored somewhere in bulk and simply forgotten about for a substantial period of time. Either way, it obviously needs to have been preserved — withstanding not only the generic factors militating against the survival of historical documents, but waves of antisemitic violence, two world wars, and the near-complete destruction wrought by the Shoah. It then needs to have been for sale and sufficiently affordable — admittedly a fluid concept, within reason, depending on the collector’s passions — to make it into one of the two collections underpinning the book. Finally, it needed to make it past me, as I tried to present a broad range of images while holding in check but by no means disregarding my own interests and predilections — not to mention purely technical constraints such as the fact that postcards, depending on their format (portrait or landscape), can only be combined on the page in a limited number of ways.

Photo courtesy of the author

To give one example for my approach, I have made a particular effort to find postcards and prints showing synagogues in their surroundings, since they reflect how Jewish communities wanted, or were able to, impress their presence on the locations in which they lived. Even after decades of studying Jewish history and despite (or perhaps due to) having spent half of my life in Germany, I had no idea just how prominently the main synagogues in many European cities featured in their respective cityscapes — and how great, consequently, is the absence created by their destruction. It is important to bear in mind, of course, that, say, The New Synagogue in Berlin with its spectacular, widely visibly cupola was only one of many (new) synagogues in the city. In substantial towns and cities, representative synagogues of this kind were the equivalent of Westminster Abbey or St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Just as there are innumerable churches in London, so too, in cities like London or Berlin, Vilna or Salonika, there were dozens of synagogues, and where Jews were prevented from establishing public places of worship, they hosted them privately in their homes.

Given how reliant many of us have become on digital images, one easily forgets that postcards and prints were never just visual representations but also objects. Prints, more often than not, appeared in publications of some kind. Unless they were too large for the page, we have reproduced them in their original size throughout, and we generally show them in their natural habitat, i.e., in most cases, readers see the entire page on which the print appeared, and we have included the original captions. Similarly, we have reproduced all the postcards in their original size and, where I had the choice, I have generally preferred copies that show traces of their use to pristine unrun copies — no effort has been made to hide these traces.

While some readers may be familiar with many of the images and many will recognize some, I am hopeful that everyone will come across something new in this book. Above all, I hope that readers will find it both informative and entertaining, our knowledge of the shadow of destruction hanging over so many of the images notwithstanding.

Photo courtesy of the author

Lars Fischer’s scholarship and publications focus on the history and conceptualization of antisemitism, Jewish/non-Jewish relations, and Frankfurt School Critical Theory. Fischer has taught at UCL, King’s College London and the University of Cambridge and served as Secretary of the British Association for Jewish Studies and Councillor of the Royal Historical Society.