Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

From Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner

In a recent essay in the New Statesman, British writer Howard Jacobson recalls how his father once had to pawn his mother’s engagement ring to make ends meet. “The idea that Jews were money-sympathetic as though by necromancy — money-adept, or just money-aware — struck us as laughable.”

Jacobson’s article counters not only a persistent stereotype, but also a long literary tradition reducing Jews’ relationship with money to connivance and greed. In the New Testament, Judas, the man whose name became synonymous with betrayal, sold out Jesus for thirty pieces of silver. The religion of the most notorious Jew in English literature, Shakespeare’s Shylock, is inseparable from his trade as a moneylender. Through the nineteenth century, Jewish characters were similarly demonized, most famously in the form of Charles Dickens’s Fagin, who teaches his band of urchins the art of pickpocketing in Oliver Twist. In American literature, antisemitic caricatures were embodied in the over-eager financier Simon Rosedale in Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth and Meyer Wolfsheim, a gambler who fixed the 1919 World Series, in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, among other instances. As late as the 1930s, The Oxford English Dictionary included a definition for “Jew” as “a grasping or extortionate person.”

Jewish stereotypes have changed somewhat in the last century, as Jewish writers entered the mainstream. Saul Bellow’s struggling Chicago immigrants are hardly financial overlords, nor are the working-class Newark characters of Philip Roth’s novels. But while such writers helped to introduce new stereotypes — the Jewish mother seems to be a relatively recent invention, and Shakespeare’s Jessica certainly isn’t a JAP — the tendency to associate Jews with avarice has yet to fade.

But while such writers helped to introduce new stereotypes — the Jewish mother seems to be a relatively recent invention, and Shakespeare’s Jessica certainly isn’t a JAP — the tendency to associate Jews with avarice has yet to fade.

“Until the twentieth century, English literature portrayed the Jew as ‘a monied, cruel, lecherous, avaricious outsider tolerated only because of his golden hoard.’” A Jew Broker, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959.

But now many contemporary novelists are examining the relationship between Jews and money without the prejudices of the past. In Jacobson’s 2016 novel, Shylock Is My Name, the Shakespearean character magically reappears in the present day, only to become enmeshed in a social drama similar to the one from which he emerged in sixteenth-century Venice. When he visits a wealthy art collector, the two discuss questions of identity, patrimony, and the real meaning of “a pound of flesh.”

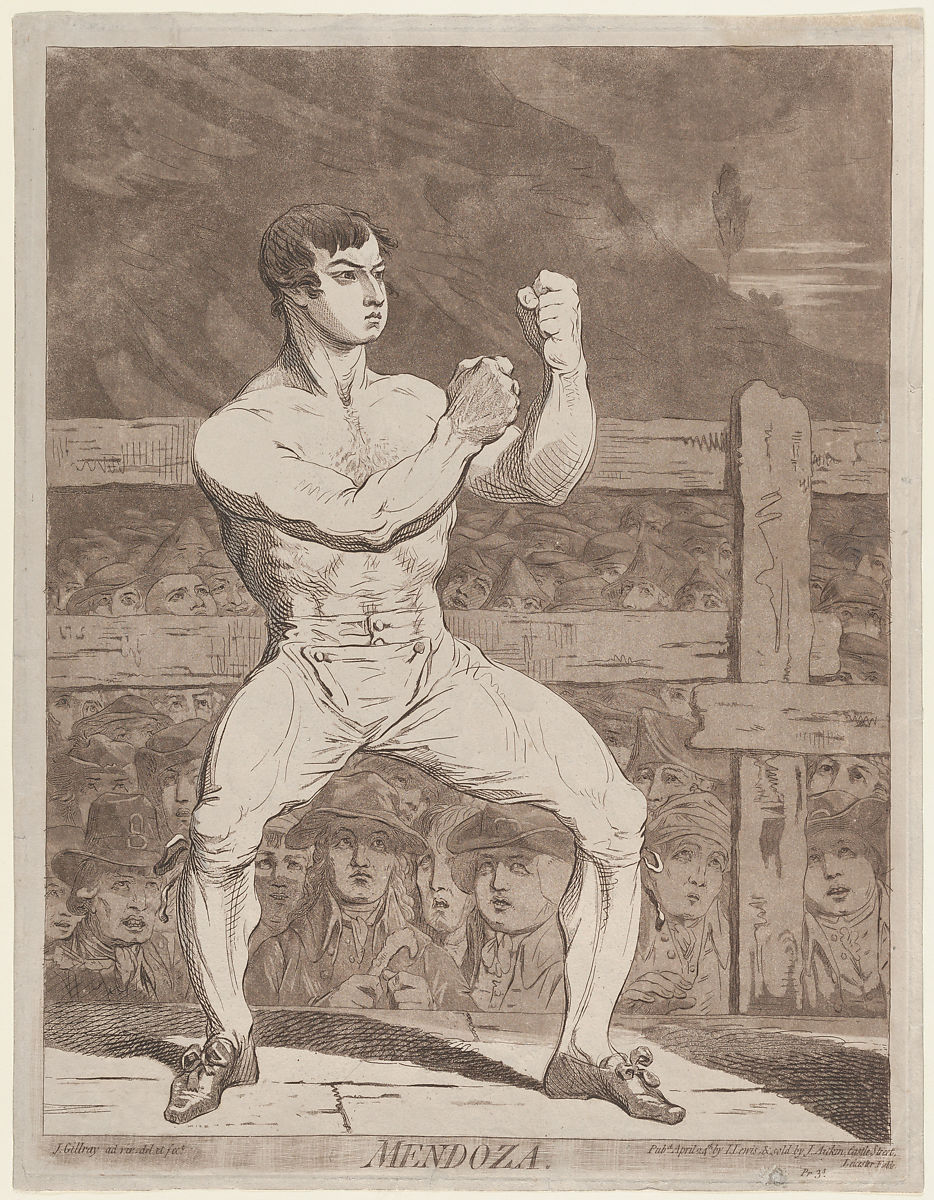

David Liss’s 2000 novel, A Conspiracy of Paper, takes as its protagonist the scion of a Portuguese Jewish trading family living in eighteenth-century London. Although Benjamin Weaver has changed his last name from Lienzo and worked as a prizefighter before becoming a thief-taker (a kind of proto private detective), he is dogged by the stereotypes that follow his family, and Jews in general, as England suffers from financial upheavals during the early days of the stock market. In one scene, Weaver visits an aristocratic client at his private club, where he is introduced as “a credit to his people, helping folks rather than tricking them with stocks and annuities.” As Liss illustrates, many Jews did become involved in the country’s nascent financial industry, but the association between Jews and money is in no way inherent. As Weaver protests, “I cannot claim to be an expert on either Jews or money. But I can assure you the two terms are not synonymous.”

Weaver’s assertion may fall on deaf ears, but in recent years, several writers have expanded on this sentiment, presenting the relationship between Jewish identity and money as entirely incidental. In two 2019 debut novels, money is depicted as a kind of emotional currency, which, rather than reducing Jewish characters to stereotypes, reveals their essential humanity.

The eighteenth-century British Jewish prizefighter Daniel Mendoza was an inspiration for the character of Benjamin Weaver in David Liss’s A Conspiracy of Paper. Mendoza, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959.

Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Fleishman Is in Trouble is a book about marriage, divorce, parenting, and midlife crises. While money isn’t a primary focus, it does make every situation more complicated, less predictable, and usually worse. The novel’s protagonist, Toby Fleishman, at first seems to disdain money altogether, and worries about the effects of the privileged upbringing he’s giving his two children. In his social milieu of business magnates, financiers, and wealthy heiresses, Toby’s profession as a hepatologist at a prestigious hospital is considered déclassé because he works with his hands and makes “only” $285,000 a year. His children’s private school and summer camp tuitions easily engulf his salary, and for his friends, a place in the Hamptons is more of a necessity than a luxury. Most of all, Toby’s middle-class mores clash with the social and financial aspirations of his soon-to-be ex-wife, Rachel, an ambitious talent agent whose sudden disappearance sets the events of the novel in motion. Comfortable with his socioeconomic background, Toby believes that there are more important things in life than wealth and status, and that their family could be just as happy — happier, probably — with a little less.

And yet, as Toby realizes, he isn’t being quite honest with himself. Despite his high-minded principles, he is willing to enjoy the luxuries his wife’s income provides. And by refusing to chase promotions, he makes Rachel feel obligated to constantly prioritize her career. Rachel isn’t motivated by simple materialism, either. Having been bullied by her private-school classmates for her off-brand clothes and inability to afford tennis lessons, she has vowed that her children will never have to suffer like she did. Her goal isn’t to earn money for money’s sake, but to give her children the ability to fit in as she never did.

While social class is a major focus for the Fleishmans, the mild Jewish background of their lives is both omnipresent and unquestioned. Their children attend day camp at the Y, and their daughter, Hannah, is busy preparing for her bat mitzvah. Toby’s closest friends — Seth, a finance guy, and Libby, a former journalist and New Jersey housewife who narrates the novel — met during their junior year in Israel. But religious identity is almost entirely incidental to the plot. As Josh Lambert points out in Jewish Currents, none of the characters’ problems are “mitigated or exacerbated by their Jewishness.”

While social class is a major focus for the Fleishmans, the mild Jewish background of their lives is both omnipresent and unquestioned.

Religion and money are similarly disconnected in Andrew Ridker’s The Altruists. Maggie and Ethan Alter, siblings from a St. Louis suburb now living in New York, struggle with the recent death of their mother, Francine, and the unexpected inheritance she left them. Maggie, the younger of the two, refuses to touch her share and instead works odd jobs in Queens, liaising for immigrants with government agencies, babysitting, and tutoring. While she couches her frugality and lack of professional ambition in moral terms — better to help the people around her, she thinks, than to become another lawyer like her friend Emma — her abstemiousness has taken a pathological turn. Giving up money leads to giving up physical nourishment; in her mind, “denying oneself a full belly kind of felt a little bit saintly.”

Ethan has followed the opposite path — quitting his consulting job, spending his inheritance, and then going into debt while living a solitary and semi-alcoholic life in his newly purchased Brooklyn apartment. In college, Ethan was at pains to conceal his family’s suburban lifestyle from a working-class crush, but he is now content to surround himself with “Bernardaud china, a La Creuset he never used, Waterford Lismore candlesticks, a white marble bread box, an electric corkscrew.” Both siblings respond to grief through their spending habits, albeit in opposite ways.

Meanwhile, the siblings’ father, Arthur, suffers his own mental and fiscal insolvency. An ambitious but underachieving engineering professor who, at retirement age, is still teaching for adjunct wages, he realizes that without his wife’s income, he can no longer afford the mortgage on their home in a gated community. After his wife discovered on her deathbed that he was having an affair, she cut him out of her will, leaving her secret investments to Maggie and Ethan. Although his abrasive personality has estranged him from his children, Arthur hatches a plan to have them visit him in St. Louis, manipulate them into giving him their inheritance, and use the money to deliver him from foreclosure. Ridker’s characters demonstrate how Jews’ relationship to money — just like everyone else’s — is a reflection of personality, and can change with their circumstances and emotional states.

Just as Jews and others can be “hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means,” so too they experience bankruptcies and windfalls, anxieties and comforts, estrangement and belonging.

The characters’ attitudes toward Jewish identity are just as varied and nuanced as their attitudes toward finances. Maggie reluctantly attends Shabbat dinner at the New Jersey home of her aunt Bex, but feels alienated by her cousins’ ostentatious brand of suburban Orthodoxy. She recalls how her uncle Levi once made her father “plunge a steak knife into the frozen earth because he’d sliced cheese with it” — a practice of kashrut that seems weirdly arcane to her. For Arthur, Judaism is no more than a matter of birth. At his wedding he struggled to get through the single Hebrew sentence required of him. Despite the fact that his late wife grew up Conservative and hated the smell of pork, his favorite restaurant is a barbecue joint named Piggy’s. Ethan is even more indifferent than his father — for him, Judaism isn’t even something to rebel against.

Between Fleishman Is in Trouble and The Altruists, a whole range of economic positions are represented; that most of the characters in these novels are Jewish is irrelevant to those positions. This, of course, is the message of Shylock himself, when, in his famous speech, he proclaims that the fundamental humanity of Jews transcends differences of faith, ethnicity, and profession. Just as Jews and others can be “hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means,” so too they experience bankruptcies and windfalls, anxieties and comforts, estrangement and belonging. As these recent novels show, money can make both enormous and subtle differences in life, for Jews as much as — but also no more than — anyone else. This realization may seem obvious, but in literature it’s been a long time coming.

Ezra Glinter is the senior staff writer and editor at the Yiddish Book Center. He is the editor of Have I Got a Story for You, a finalist for the National Jewish Book Award. He lives in Brooklyn, NY.