Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

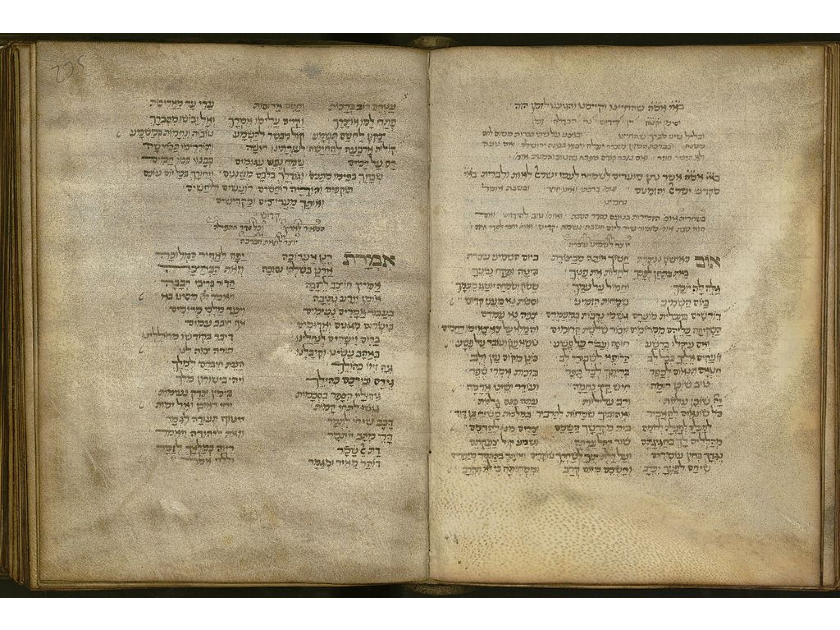

A Jewish prayer book, from The National Library of Israel Collection

COVID-19’s descent upon us brought innumerable challenges, not least among them is the foreclosure of our traditional ways of mourning. Limited attendance at funerals and condolence visits is hard for both the mourner and those who wish to comfort; the inability to say Kaddish with a minyan — a prayer quorum of ten — is one more avenue that is unavailable to many. I lost my mother more than three years ago, and found comfort in the tradition of reciting kaddish daily with a minyan, but I did have a surprising encounter that may bring solace to those who have lost loved ones this year, and are unable to recite the traditional Mourner’s Kaddish in a traditional setting or circumstances.

Saying Kaddish for an entire year, as documented in my recently published book My Year of Kaddish: Mourning, Memory and Meaning, allowed me both the time and space to mourn the passing of my mother — a rare gift in modern times. It was a challenging year, to say the least. I rose at daybreak to arrive at the daily minyan on time, and overcame my hesitation to say the Kaddish out loud, but my work as a trauma psychologist sent me to far flung places where a minyan could not be found. How could I deal with that?

Up until my trip to Nepal — to complete a resilience building project begun in the aftermath of the 2015 earthquake — I said Kaddish with a minyan daily. A few weeks prior to my trip, as I was contemplating the impact of missing my daily Kaddish for the first time, I fished around the internet for some glimmer of a solution. What I encountered was the Kaddish Yachid, the Individual’s Kaddish, which can be said when no minyan is available. I was astounded. I had never heard of this version of the prayer. Checking with more erudite people around me, I discovered that they were not familiar with it either.

I rose at daybreak to arrive at the daily minyan on time, and overcame my hesitation to say the Kaddish out loud.

The authorship of this unusual Kaddish is attributed to the ninth century Rav Amram Gaon, head of the great Talmudic Academy of Sura, Babylonia; he is most famous for his prayer book which survived the passage of time and formed the basis of Jewish prayer service traditions that evolved over the millennia. So, while the Individual Kaddish, or Kaddish Yachid, is not very well known today, it seems to have a long-standing foothold in Jewish tradition. Why had I not heard of it?

Kaddish is a prayer that makes no mention of death or loss. It is a prayer that sanctifies God, and talks about the Kingdom of Heaven. At a time of great loss we are often sent adrift, losing our anchor in life, in belief, and in all we hold true. Hanging on to the Kaddish directs us and reminds us that God is there and we are not in charge, nor can we expect to understand. It ends with a request to God that he grant us peace — a peace we so desperately need when our hearts and souls are in turmoil in the aftermath of loss. The Individual Kaddish is actually quite similar in content to the Mourner’s Kaddish, and brings comfort in similar ways. It reminds us that we are not alone in the world, and also gives us a time out from life to consider our loss.

One of the ways that saying Kaddish alone is quite different than saying it with a minyan is the social or community aspect. Saying Kaddish in a minyan means that your loss is acknowledged by neighbors and friends, and a feeling of support and connection to the community often develops. Psychologists have documented that social support is one of the keys to resilience, and although the mourner may be oblivious to this in the early days of mourning, as the year continues, that sense of fellowship grows. This will of course, and unfortunately, be absent for those saying the Individual Kaddish.

Nevertheless, doing something active in the face of death, even if that “something” is done alone, can be very healing. The Individual Kaddish is just once such activity, that may suit some, but not others. What other kinds of activities can a person choose to do in the wake of a loss? What personal rituals can be created and become meaningful? Whatever it is, whether it be the Individual Kaddish, or something entirely different or unique, and especially dedicated to the person one has lost, this ritual can help acknowledge the loss and allow space for the mourning process to proceed.

For me as I prepared to depart for Nepal, I was reassured that saying the Individual Kaddish — even in the privacy of my hotel room — might bring me some comfort, and allow me to continue to mourn the loss of my mother. Upon arrival in Kathmandu, I discovered to my delight that my room overlooked a picturesque courtyard filled with colorful Buddhist prayer flags flapping in the wind, sending out blessings of peace to the four corners of the world. As planned, I recited the Individual Kaddish aloud in the privacy of my hotel room every morning and found it both grounding and reaffirming. The Individual Kaddish carved out a space for me to remember my mother, even in Nepal. I blessed her on her journey — wherever she was). This connection was precious. I concluded with the traditional blessing of peace, as my Individual Kaddish joined with the Buddhists prayer flags sending our combined blessings of peace to all people of the world.

Click here for the Kaddish Yachid of Rav Amram Gaon in Hebrew with an English translation.

Naomi L. Baum, Ph.D., a psychologist, who consults both in Israel and internationally in the field of trauma and resilience. She is the author of professional articles on resilience building and trauma as well several books, including, her newest book, ISRESILIENCE: What Israelis Can Teach the World. She lives with her husband in Efrat, and is mother of seven, and grandmother of twenty one.

Her website is: http://www.naomibaum.com