Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Like most people, I used to view doubt and faith as occupying two opposite ends of the spiritual spectrum. In my mind, there were people of faith, True Believers, and then there were the Doubters, like myself. A vast and impassable ocean separated these two groups. Or so I thought.

Like most people, I used to view doubt and faith as occupying two opposite ends of the spiritual spectrum. In my mind, there were people of faith, True Believers, and then there were the Doubters, like myself. A vast and impassable ocean separated these two groups. Or so I thought.

I don’t think that way anymore. After traveling the world and diving into several of the world’s major religions (and a few minor ones), I’ve concluded that doubt represents not an absence of faith, but rather, is an integral part of it. I wouldn’t say I celebrate doubt, not anymore than I celebrate that pain in my left knee telling me I need to see the doctor. But I do accept it, value it, and recognize its role in the spiritual life.

True some religious people desire certainty— and only certainty. For them, doubt represents weakness, an absence of faith, or at least an incomplete faith. In short, doubt is the enemy. But that is only one way of being religious. There are others. Psychologists have identified the “quest personality.” That is one category that I – and many others I expect– fit into perfectly. A Quester is someone who seeks knowing full well she will never find definitive answers.

Doubt can paralyze, yes, but it can also motivate. The opposite of doubt is not certainty but action, forward momentum. As E.F. Schumacher, the renegade economist put it, “Matters that are beyond doubt are, in a sense, dead; they do not constitute a challenge to the living.” In other words, matters that are beyond doubt have nothing to teach us.

In my travels, I’ve met many deeply religious people who, nonetheless, live comfortably with doubt. My friend James, for instance, is a Buddhist who still has many doubts — about reincarnation, for instance — but this does not prevent him from practicing his faith, and benefitting from it.

Nearly all religions, in varying degrees, acknowledge the role of doubt, but perhaps none more so than the Jains, the ancient faith based in India. The Jains have a term, syadvada, which literally translates as a “multiplicity of viewpoints,” but is also referred to as “maybe-ism”.

Essentially, syadvada says that for every “truth” that we hold dear there are other, equally valid, truths. For the Jains, syadvada is a way of life, and it permeates every aspect of their faith, including their doctrine of nonviolence.

The Jains know instinctively that where certainty reigns, nothing else can survive. Where there is doubt, there is also possibility. And life.

A version of this article appeared on Washingtonpost.com.

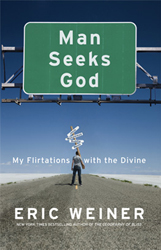

Eric Weiner is a former foreign correspondent for NPR, a philosophical traveler — and recovering malcontent. His new book, Man Seeks God: My Flirtations with the Divine, is now available.

Eric Weiner is the author of the New York Times bestsellers The Geography of Bliss and The Geography of Genius, as well as the critically acclaimed Man Seeks God and, his latest book, The Socrates Express: In Search of Life Lessons from Dead Philosophers. A former foreign correspondent for NPR, he has reported from more than three dozen countries. His work has appeared in the New Republic, The Atlantic, National Geographic, The Wall Street Journal, and the anthology Best American Travel Writing. He lives in Silver Spring, Maryland, with his wife and daughter.