Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

This piece is part of our Witnessing series, which shares pieces from Israeli authors and authors in Israel, as well as the experiences of Jewish writers around the globe in the aftermath of October 7th.

It is critical to understand history not just through the books that will be written later, but also through the first-hand testimonies and real-time accounting of events as they occur. At Jewish Book Council, we understand the value of these written testimonials and of sharing these individual experiences. It’s more important now than ever to give space to these voices and narratives.

In collaboration with the Jewish Book Council, JBI is recording these pieces to increase the accessibility of these accounts for individuals who are blind, have low vision or are print disabled.

Over the Passover holiday this year, I released a children’s book that tells the story of my grandfather’s life. The book, My Zayde is a Superhero, chronicles the experiences of Ernest Rothschild, who served in the US Army in World War II after fleeing persecution for his Jewish faith in Nazi Germany.

My grandfather passed away when I was only five years old. My memories of him are hazy, cobbled together images and fleeting moments — a seder here, a birthday there — and undoubtedly influenced by the stories that have been told to me over many years. He never discussed his military service, and rarely discussed his experiences in Germany in the late 1930s. But amid a surge in antisemitism and a growing number of young people in the United States doubting the veracity of the Holocaust, I felt compelled to return to what I knew was a story of resilience and unusual courage in the face of great evil.

A man who stood amidst the shattered glass of Kristallnacht in Frankfurt in 1938 would stand in the ruins of Adolf Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest in Berchtesgaden in 1945. But in an American uniform.

Shortly after my grandfather passed away, about a month after I had last seen him, I came to believe I was responsible for his death.

To this day, I cannot understand how or why I believed I was at fault. I had no reason to think I had anything to do with the matter, the cause of death having been pneumonia and late-stage lung cancer. Still, there I was, laying in my childhood bed, going to sleep at night, feeling painfully, shamefully guilty that I had somehow offed my grandfather.

Author’s grandfather in the ruins of Adolf Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest

I never said a word to anyone about it, and, with time, I would come to understand that these thoughts are common in children. Psychologists call it “magical thinking,” the idea children have that they are somehow at fault for horrible tragedies.

While magical thinking is a cause of unnecessary strain in children too young to understand mortality, the belief that there are forces beyond our understanding that guide us, and possibly even connect us to those who have passed beyond, are more typically accepted, though perhaps magical in their own way.

And so a few days after October 7th, I was thinking of my grandparents when a light, a tableside lamp, turned on in my room. The sudden brightness was startling. The lamp had only a turn knob. It seemed an unknown force made itself, or themselves, present.

The antisemitic protests that plagued the United States and the world in the wake of October 7th had already started. The brutality of Hamas’s terror was followed, infuriatingly, by the eruption of virulent and long-simmering, but thus far socially unacceptable, hatred of Jews.

In this context, I was determined to confront the surge in antisemitism in the ways I could. My thoughts returned to my grandfather, a man who had not been, so to speak, “a Jew with trembling knees.”

My grandfather’s commanding officer in WWII had written a book about their service, describing, at one point, my grandfather’s “awesome but understandable” hatred of the Germans. As a child living in prewar Germany, he had been beaten up by antisemitic thugs who felt powerful making another person suffer. You hear echoes of this twisted cruelty in the taunts hurled at Jewish college students, and in the glee of the Hamas fighter bragging to his father: “Look how many I killed with my own hands! Your son killed Jews!”

My grandfather’s family moved from Pfungstadt to Frankfurt in 1934 hoping that the anonymity of the city would provide some protection. His father, unable to continue his business, took a job washing clothes at the Jewish hospital. And it was while walking to his job, in the early morning darkness of November 10th, 1938, that my great-grandfather saw the synagogues burning in a raging fire, engulfing the city in black smoke.

My grandfather’s mother was a force as well, courageous and calm amid the increasingly violent commotion of that November pogrom that would come to be known as Kristallnacht. (She had prevented an earlier arrest of her husband, staring down the cocked rifles of German stormtroopers.) She quickly told my grandfather and his younger brother to hide in the Jewish hospital with their father.

On the afternoon of November 11th, they returned to their apartment without my great-grandfather, who had been discovered and arrested at the hospital. At home, they found unimaginable destruction. Plumbing fixtures had been ripped from their fittings and piles of shattered glass and broken mementos covered the floors. Their pet parakeet, whom they had patiently taught to speak, lay still in its cage.

It was in this moment, I believe, that the Nazis, in their attempt to burn to death the Jewish spirit, in fact ignited the flames of a soul on fire, blazing within Ernest Rothschild.

As soon as my great-grandfather was released from Buchenwald, reportedly due to his WWI military service, my grandfather and his family fled to Holland and then to the United States. My grandfather’s high school studies were initially complicated by his parents’ now impoverished condition and his lack of English proficiency; but he learned quickly and in a short time, joined the US Army. He completed initial training in Macon, Georgia, before moving on to Class 10 at Fort Ritchie, Maryland.

In the Catoctin Mountains, not far from Camp David, he joined many other German Jewish refugees, with personal stories similar to his own. These soldiers trained in psychological warfare, interrogation tactics, and enemy military organization, also known as “Order of Battle.” The details of the secret program, declassified relatively recently, still remain largely unknown to the public, but the so-called “Ritchie Boys,” who dispersed throughout the Army after they completed training, are responsible for collecting an estimated 60% of actionable intelligence in the European theater.

About a month after October 7th, on Veterans Day 2023, I drove a few hours from Washington D.C. to Fort Ritchie, Maryland, to see where my grandfather had trained. The serene grounds seemed a stark contrast to the horrors of war that awaited the brave men who once slept in the barracks there. At the time, I knew my grandfather had served in Army intelligence and that his name was listed in the back of a book on the Ritchie Boys, but at the fort we would be able to check his service number definitively.

On that Veterans Day, the sky was gray and overcast. As we approached Ritchie, a single beam of light burst through the clouds and illuminated the gate. I found him, I thought. He was here.

After Ritchie, my grandfather made his way up through North Africa, Italy, France, and on to Germany. It was in Germany that his commanding officer would note a certain smoldering in his eyes, but I imagine it was always present, fueling him at each campaign, at every stop, during every mission. In a letter, he would describe his delight at pulling a Nazi out of bed at seven in the morning on a Sunday.

Author’s grandfather in a graveyard

His fellow soldiers documented their journey, capturing, in a photo, my grandfather standing in a graveyard, his hands on his hips, staring at a culpable looking German. My grandfather had discovered a Jewish cemetery had been desecrated. Those involved “shook from top to bottom,” he wrote, “but I was so furious.” Sergeant Rothschild arranged for immediate repairs and told the mayor to cut the cemetery grass too.

In his birthplace of Darmstadt, not far from the mythical hilltops of Frankenstein Castle, he would learn that his childhood home had been occupied by a high-ranking official at IG Farben, the company that made the gas chamber chemicals. A young lady, not knowing who he was, told him the house was destroyed in an air raid in 1944 on, of all days, his birthday. “What a coincidence,” he observed.

And in nearby Pfungstadt, he would find a teacher who had warned of the Nazis’ worst intentions. The teacher, who had not seen him in eleven years, recognized him immediately. Before my grandfather could identify himself, he went to the kitchen and retrieved a photograph of a young boy, Ernest Rothschild, noting he had looked at it just that week. Never would the teacher have imagined that this little boy would turn up on his doorstep only days later as an American soldier. But, there he was.

Another coincidence in the shadows of Frankenstein Castle, perhaps. A teacher’s instincts of a student’s arrival. A house shielding evil destroyed on the birthday of its target. A light turning on without the switch. A beam through the clouds at the right moment. Magical thinking.

At the climax of My Zayde is a Superhero a scene unfolds that shows a fictionalized version of another real photograph taken by my grandfather’s fellow soldiers. The photo shows him standing amidst the ruins of Hitler’s living room in his favored hideaway at Eagle’s Nest in Berchtesgaden. The peaks of mountains are visible in the background, and his feet are surrounded by rubble. He is strong and triumphant in an American uniform.

On that towering cliffside in 1945, my grandfather looked out over the land that was once his home, having suffered unthinkable loss and endured unimaginable fear. Here, my grandfather arrived not only as a survivor, but as a fighter, a hero not only in action, but also in spirit. In an eagle’s nest rose a phoenix, one who would not be made to lie still in his cage, born in flames, ascended from the ashes, fueled by a soul on fire.

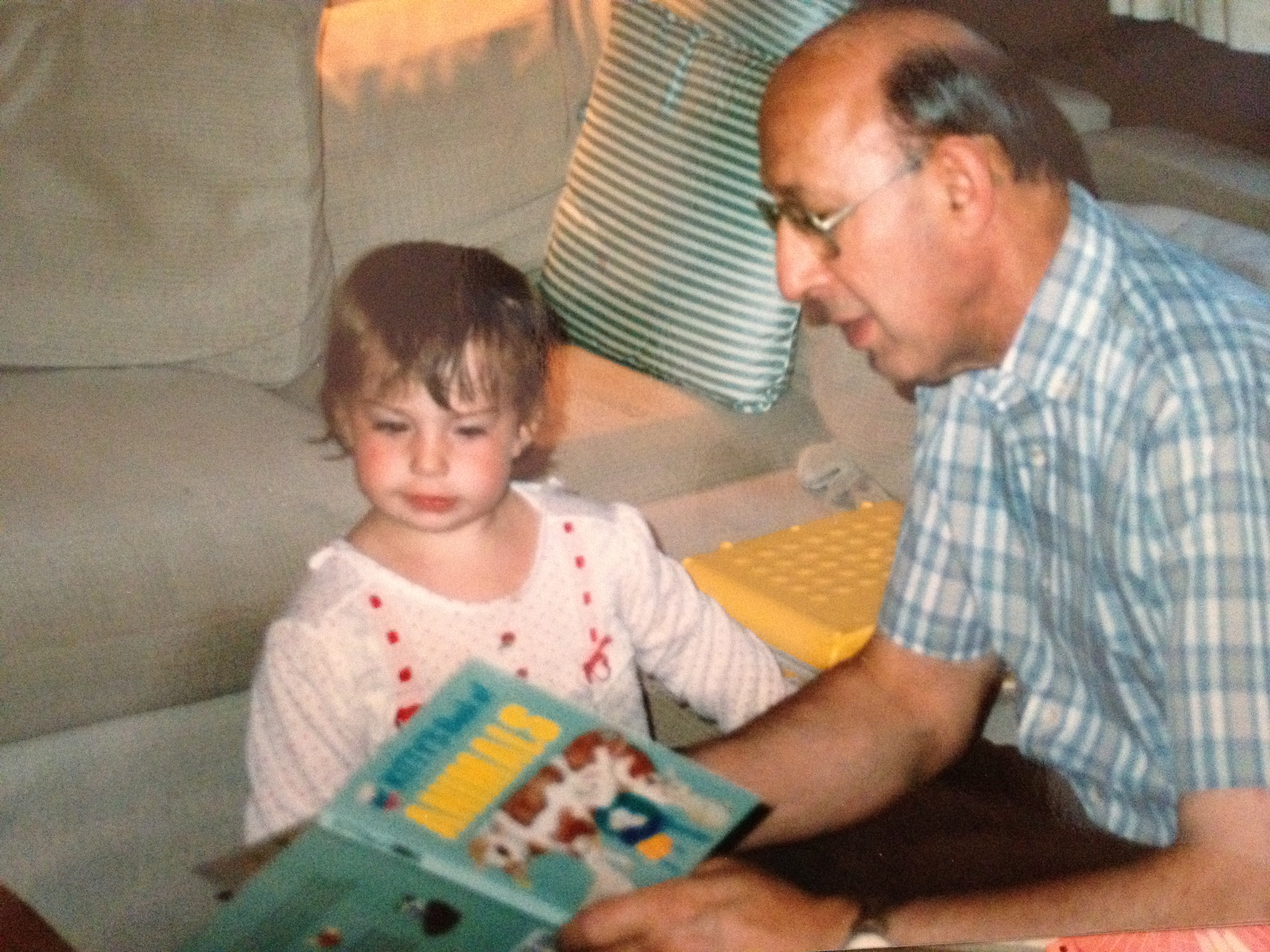

Th author as a child being read to by her grandfather

The views and opinions expressed above are those of the author, based on their observations and experiences.

Support the work of Jewish Book Council and become a member today.

Amanda J. Rothschild is a national security expert and former senior official at the White House, National Security Council, and State Department. She is the author of the first children’s book on the Ritchie Boys, My Zayde is a Superhero: The True Story of an American Jewish Boy Who Survived and Fought Back.