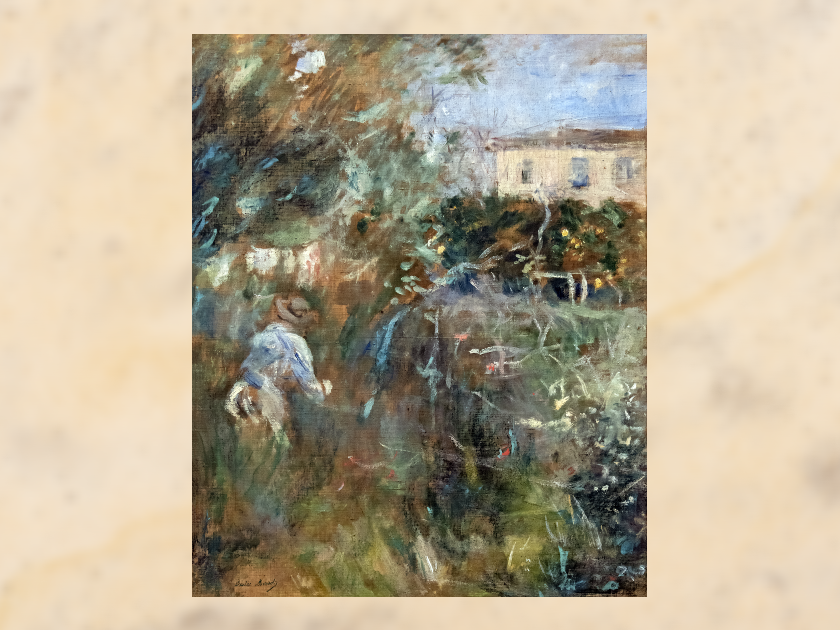

Femme au jardin (Villa Arnulphi à Nice), by Berthe Morisot, 1882

Fondation Bemberg Toulouse

Writing historical fiction involves the intricate blending of both fact and fabrication. In the case of my new novel, The Lost Masterpiece, I spent countless hours researching the goings-on in Paris from the late-nineteenth century through World War II; then, even more effort wrestling this information into a story that — I hope — rings true, reveals both the known and unknown of that time, and entertains.

One of the most fascinating topics I explored was the return of Nazi-stolen artworks to their rightful owners. As a Jew, an academic, and an insatiable reader, I was already familiar with this orchestrated plunder of hundreds of thousands of artworks, designed to erase Jewish culture while enriching the Third Reich. Hermann Göring, in particular, cherry-picked stolen masterpieces for his personal collection, along with those that would be displayed in Hitler’s post-war Führermuseum — a museum that fortunately never came to fruition.

What I didn’t know much about was the restitution process: to find these artworks and return them to the families from whom they were stolen. This process began at the end of the war and has continued to this day. As soon as I began reading about this arduous endeavor, I was hooked. Part of what I love about writing historical fiction is discovering a fact, a story, or a moment that I know will pull the narrative together.

In the case of The Lost Masterpiece, I was searching for a link between the past and my contemporary throughline. The past storyline follows the life of the unsung artist Berthe Morisot, an extraordinary early Impressionist who worked alongside Monet, Renoir, Manet, and Degas — the only woman amongst them. I wanted to counterbalance her life with a contemporary narrative that would shed light on what had happened to her legacy after she died, particularly the misogyny that largely buried her work. I needed a connection between the two storylines and I had a feeling there was something in my historical research that was going to do just that. I had no idea what aspect would spark my novel into being, but I was certain if I spent enough time, I would find it.

I dipped into books on the subject: The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War by Lynn Nichols, The Lost Museum by Héctor Feliciano, and The Lady in Gold: The Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt’s Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer by Anne-Marie O’Connor. I watched documentaries: PBS’s Plunderer: The Life and Times of a Nazi Art Thief and director Jane Chablani’s Stealing Klimt. And I listened to podcasts including Art Bust and Dan Snow’s Hunting Stolen Nazi Art. And of course, the movie The Monuments Men (based on Robert M. Edsel’s book by the same name). All of which I would highly recommend.

Writing historical fiction involves the intricate blending of both fact and fabrication.

After months of research, I finally found my spark — the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. Formed in 1951, its mission was to secure compensation for Jewish victims of Nazi persecution. It made me wonder: What if a painting stolen by the Nazis and assumed destroyed actually survived? And what if this miraculous painting is returned by the Claims Conference to the only living heir decades later bound up in„mysteries and secrets she must unravel? It could work. But not easily.

However, it turns out that, although part of the Claims Conference’s mission is recovering stolen Jewish property and overseeing reparations, neither of these is its primary focus. In actuality, its role is more administrative than action-oriented. Such as negotiating contracts with the German government to create and expand numerous compensation programs; overseeing the distribution of reparations delivered by other agencies that provide direct services to survivors; recovering and selling Jewish property where there is no living heir, in order to aid those who had managed to outlive the horror; funding Holocaust education and research to document history and teach it to future generations.

While all of these aims are praiseworthy and necessary, none of them were helpful for the purposes of my book. Scenes of bureaucrats filing reports and designing curricula, no matter how honorable, do not make a compelling novel. But I was completely taken by the idea and was reluctant to let it go.

And this is where the magic historical fiction comes in. Sure, the real Claims Conference isn’t directly involved in the recovery of the lost artwork. Nor are they dealing directly with the disbursement of stolen property to individuals. But what if my fictional version of the Conference was?

What if a lawyer working for the Boston office of the Claims Conference — which doesn’t exist — was responsible for returning a missing painting? What if he brought it to a woman who had no idea she had ancestors living in France during World War II? What if it was a multi-million-dollar masterpiece by Édouard Manet that had been missing for eighty years? And what if the central figure in the painting was Berthe Morisot?

The ideas kept pumping. What if the painting had mysteriously survived when other artwork around it had not? What if Manet didn’t actually paint it? What if a ghost inhabited it with a mission to expose the truth? While some of these ideas stuck and others did not, three years later, with the help of the Claims Conference, The Lost Masterpiece is the result.

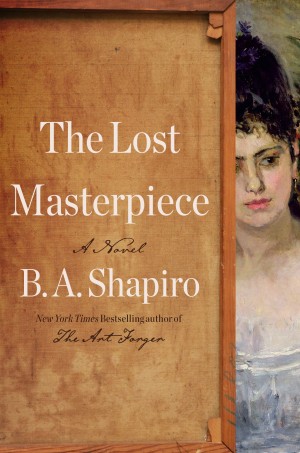

The Lost Masterpiece by B. A. Shapiro

B. A. Shapiro is the bestselling author of The Collector’s Apprentice, The Muralist, and The Art Forger, which won the New England Book Award for Fiction and the Boston Authors Society Award for Fiction, among other honors. Before becoming a novelist, she taught sociology at Tufts University and creative writing at Northeastern University. She and her husband, Dan, divide their time between Boston and Florida.