Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Photo by Claudio Schwarz on Unsplash

My father died unexpectedly from complications of a routine surgery in October 2016. I was twenty-nine at the time and on the go in New York City, working by day at a Jewish nonprofit and, by night, attempting to be a playwright. His death came as the single greatest shock of my life. My father had been my lodestar — the person who’d shaped me the most, who’d nurtured my passions, who’d exposed me to films, plays, books, and art (and the Yankees). Now, without warning, he was gone.

I retreated to my one-square-mile hometown in northern New Jersey to be with my distraught mother and sit shiva; we performed the rituals of mourning and received the condolences of family and friends. And then, shortly after — far too shortly, in retrospect — I did what any twentysomething budding dramatist who’d lost a beloved parent and didn’t know how to cope might do: I wrote a messy play about the whole ordeal. Unsurprisingly, this misbegotten project never amounted to much; the piece had a couple of public readings and soon fizzled out, as it should have. The experience was still too raw and painful for me to make any kind of artistic sense of it. I was frantically writing, instead of giving myself space to grieve.

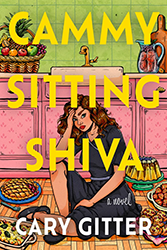

Flash forward more than six years to the beginning of 2023. I was thirty-five now, married, and, wonder of wonders, living in the Midwest, where I’d relocated after meeting my wife. I found myself in a reflective mood, maybe because it was the start of a new year, and something told me I should finally try to revisit the thorny subject of grief — though not in a play this time, but in the less constrained form of prose. So, on a cold January night, I sat down and typed the first sentence of what would become my debut novel, Cammy Sitting Shiva: “Cammy was adrift at a party the night her dad died.” And sure enough, I realized that, with the dual benefit of distance and perspective, I at last had the capacity to confront the loss of my father while transforming that loss into fiction that could stand on its own two feet — fiction leavened by irony and, yes, even abundant humor.

I found myself in a reflective mood, maybe because it was the start of a new year, and something told me I should finally try to revisit the thorny subject of grief — though not in a play this time, but in the less constrained form of prose.

This element of humor is the core of why, to me, Cammy Sitting Shiva is a deeply Jewish book. The story centers on a young Jewish woman going home to sit shiva for her father. But Cammy is no pious protagonist. To the contrary, she’s a bit of a train wreck, behaving outrageously to escape her grief and bristling at the strictures of ritual and religion — as embodied by the earnest Rabbi Wiener — with sardonic wit. Yet this darkly comic response to tragedy, this irrepressible urge to quarrel with God, is, I think, part of a rich Jewish tradition of skepticism and argument — a tradition woven into Cammy’s “acting out” and her continuous stream of quips and complaints. In this way, I hope the novel is reverent in its irreverence.

Ultimately, by the end of the fraught week of shiva — after screwing up royally and alienating everyone close to her — Cammy is able to find some peace and a path forward through a sort of spiritual reckoning at her father’s grave. And I, too, found something through the writing of this book. Though I wasn’t fully aware of it during the nearly yearlong drafting process, I recognized afterward, in reading over the manuscript, what I was really doing all along: I was reliving my father’s death and its aftermath, from the safer vantage of hindsight, to seek the closure I never attained the first time around. I was rendering the chaotic experience as a coherent story. And perhaps most importantly, I was crafting my own modest literary memorial to my late father.

On the verge of the publication of Cammy Sitting Shiva, I think of the customary Jewish saying upon someone’s passing: “May their memory be a blessing.” A simple, eloquent phrase that avoids mawkishness while evoking how our loved ones remain with us after they depart, how their legacy continues to inform and guide us. I think of my father bringing home books from the public library when I was a child and leaving them on my bed for me to discover — just one of the myriad ways he encouraged my love of words, of expression, of storytelling. I imagine how he might feel knowing that a novel largely inspired by him will now live on library shelves for others to discover. As I linger on this bittersweet notion, a slight variation on the familiar benediction comes to mind, a variation that conjures the enduring power of text as testament: “May his memory be a book.”

Cammy Sitting Shiva by Cary Gitter

Cary Gitter is the author of the plays The Steel Man, Gene & Gilda, and The Sabbath Girl, among others, and the co-creator of the musicals The Sabbath Girl and How My Grandparents Fell in Love. His work has appeared off-Broadway and at theaters around the country, and he is the playwright-in-residence at Penguin Rep Theatre in Stony Point, New York. He grew up in New Jersey and now lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with his wife, Meghan, and their two dogs, Roo and Puck. This is his first novel.