Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

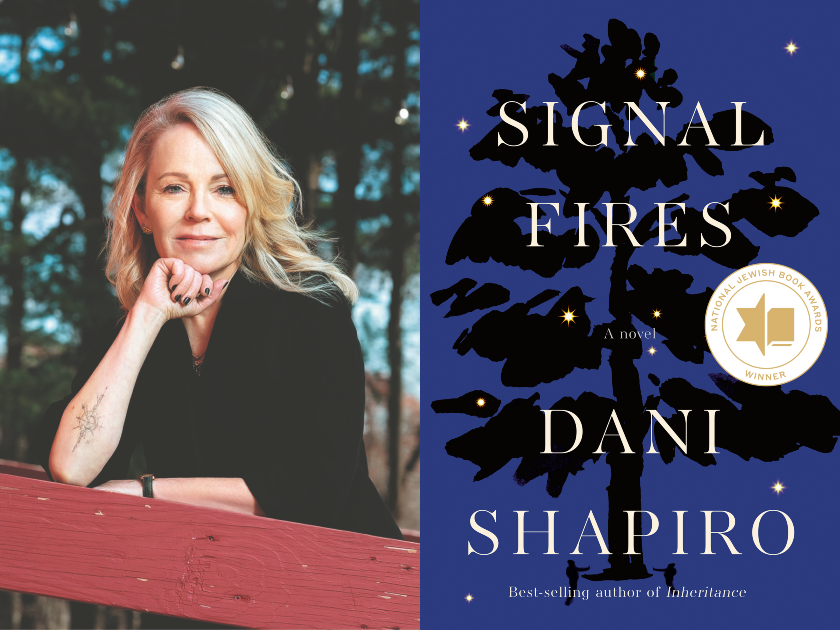

Author Photo by Beowulf Sheehan

Simona Zaretsky speaks with Dani Shapiro about her novel Signal Fires, winner of the 72nd National Jewish Book Award in the Fiction category. They explore perception of time and memory, shifting family dynamics, and how Judaism weaves throughout this propulsive and poignant novel.

Simona Zaretsky: Signal Fires begins with a cataclysmic accident that sets the Wilf family’s lives in motion in separate ways. The family dynamic changes and there’s a slow reversal of parenting roles. Could you speak on the shifting family dynamics?

Dani Shapiro: When the Wilfs make tacit agreement never to discuss what really happened on the night of that cataclysmic accident, it alters the trajectory of each of their lives. I have a philosophy that when a great trauma happens to us is as, if not more, important than what it is that has happened. The Wilf kids, Theo and Sarah, are teenagers at the time of the accident. They’re in the process of becoming who they are. And so the silence, the secrecy, and the tragedy itself are all hugely formative. For their parents, Ben and Mimi, the secrecy and silence is also toxic, but it’s a quieter toxicity. It impacts their lives less visibly. Dynamics in families always shift as decades pass, but in the case of this family, it’s more dramatic and intense, underscored by their inability or unwillingness to talk about it.

SZ: Judaism has such defined stages of life and life cycle events. With the non-linear structure of Signal Fires, there is an inversion of the idea of life, and success, as linear. Could you speak to this structure? Does Judaism, or a Jewish sensibility of time, play into it at all?

DS: Such an interesting question. My sense of time has a great deal to do with memory and consciousness. Time is, of course, always marching inexorably forward, and yet I don’t think, in our internal lives, that we experience time in a linear fashion. Memory isn’t narrative. Consciousness is most definitely not narrative. Perhaps this is part of the power of storytelling, and the power of defined stages of life cycle events. I wanted to refract time, in Signal Fires, to experience the lives of these characters in all their stages, in all their layers. I don’t know how to separate a Jewish sensibility of time from my sensibility of time. They may be one and the same.

SZ: Mimi’s experience of Alzheimers is poignantly captured from her own perspective, as well as from that of her family members watching the changes occur. To me, the weaving together of narratives and time lines felt reflective of the act of remembering itself. Could you speak on memory, or the experience of writing memory loss from several perspectives?

DS: I witnessed my beloved mother-in-law’s slow decline from Alzheimer’s over the course of a decade, and the dawning realization she and my father-in-law had in the beginning, before it was truly obvious that she was declining. I wanted to capture Ben’s denial, particularly as a doctor, because as a husband he was missing the signs. But then I realized that I needed, as a writer, to enter Mimi’s consciousness when she is far along in the disease, living in the memory unit. And what I realized – and of course this isn’t true for everyone – but in Mimi’s case, love was what remained. Love was what propelled her toward her children, toward her husband, even as she became unstuck in time and space, she knew who she loved. That was something that very much struck me about my own mother-in-law. In the year before she died, my son visited, and though she didn’t know his name, or possibly who he was, she knew she loved him. She kept saying “kinahora” again and again.

SZ: Through a silence that becomes harder and harder to break through, the Wilf family members each attempt to come to terms with the accident. Could you speak to the portrayal of grief and mourning?

DS: It’s funny, I don’t think that grief and mourning have a center seat in Signal Fires–even though there are losses and hard moments, I feel that a sense of hope and connection are what override the sorrow. And in part, it’s the non-linear structure which allows for that, because we’re given glimpses of these characters at different moments in their lives – including glimpses of their futures – and so in some way we know that in the fullness of time, they will experience love and connection.

I wanted to refract time, in Signal Fires, to experience the lives of these characters in all their stages, in all their layers.

SZ: Division Street and its gorgeous, towering oak, are so richly drawn. The reader sees how tightly-knit the neighborhood is and yet, simultaneously, there is a vast distance between community members, and a discrepancy between the appearances of different families and the reality of their relationships behind closed doors. How does the setting play into the plot and inform the lives of the characters?

DS: I was (and am) very interested in exploring neighborhoods and communities in my writing. These people moved to Division Street, set down roots there, raised their children, attended community events together, but may not have a whole lot more than that in common. And yet there is an intimacy in witnessing one another’s lives: the comings and goings, the trash being taken out, the dog being walked, the kids becoming friends, or not. And at the same time, those years of family life in a neighborhood are finite. We never think of that while we’re living those years, but I was keenly aware, while writing Signal Fires, of active parenting being a chapter in our lives, and not the whole of our lives. And so when the novel opens, and Ben is finished packing up the house he’s lived in for forty years, where he was a young husband, a young father, a young doctor, and he is anticipating the next chapter, and thinking back to earlier times, that’s what I was hoping to capture.

SZ: Waldo Shenkman and Ben Wilf have a connection that exists outside of their nuclear families and offers each of them a distinct kind of support and sense of being seen. Constellations and astronomy play such a pivotal role in this – what kind of research did you do for this piece? And how do you see constellations and astronomy fitting into Waldo and Ben’s relationship over the years?

DS: Waldo’s obsession with the cosmos is the way he comes to understand the world and feel (paradoxically) grounded. He’s a brilliant, lonely boy whose parents don’t understand him, and he feels a kinship with Ben. I’ve always been fascinated by the kinship we sometimes feel with people we don’t know well, or even perfect strangers. Where does it come from? What does it mean? As for research, Waldo was a boy genius, and I just tried to keep up with him, so I read everything I thought Waldo would read, and then the app that Waldo loves, Starwalk, was also instrumental. (It’s a real app, by the way.)

SZ: What were your literary influences? Was there a particular moment of inspiration for the book?

DS: Influences! I have many, but there are three I return to again and again. The first is Virginia Woolf. There is actually a passage in Signal Fires in which Ben is thinking about the way time works, in which I was extremely conscious of Woolf’s ghost on my shoulder. The second is Joan Didion, for the stunning clarity of her sentences and a kind of fearlessness inseparable from her fragility. As for inspiration for the novel, there wasn’t a single one, but rather, as often happens for me, the collision of thoughts, ideas, landscape, and characters that all came to me at different moments. I needed all of them in order to embark on the book.

SZ: Signal Fires includes a section set in 2020 – could you tell me about your experience of writing about the early days of the pandemic? And what was it like to return to writing fiction after your recent memoirs?

DS: It was thrilling to return to fiction. I’ve missed it terribly. After I finished my memoir Inheritance, I truly couldn’t imagine what could possibly come next. I had finished a body of work, in memoir, that began with Slow Motion and ended with Inheritance. Not that I might not write another memoir at some point, but in terms of that body of work, I had found what I hadn’t even known I was looking for. And so, it was an extraordinary experience, becoming reacquainted, during the pandemic, with the 100 pages I had written years earlier. I realized that a glimpse of 2020 might impact this stalled novel that I had lost the thread of years before. That was one of the most exciting moments, creatively speaking, that I’ve ever had. I wasn’t interested in writing a pandemic novel at all, but I saw a way to weave a small thread of 2020 into the overall tapestry.

SZ: What are you currently reading?

DS: I’m about to read Rebecca Makkai’s I Have Some Questions For You, and also Ann Napolitano’s Hello Beautiful. Ann is a former student of mine, and I am immensely proud of her, and all my students who have published books over the years.

Simona is the Jewish Book Council’s manager of digital content strategy. She graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with a concentration in English and History and studied abroad in India and England. Prior to the JBC she worked at Oxford University Press. Her writing has been featured in Lilith, The Normal School, Digging through the Fat, and other publications. She holds an MFA in fiction from The New School.