Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

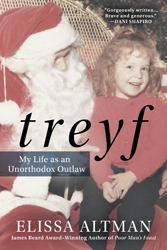

Earlier this week, Elissa Altman shared how her memoir Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw found a receptive audience in coastal Maine. Elissa is guest blogging for the Jewish Book Council all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

It is the end our end-of-summer vacation in Maine, an annual trip that started out as a vacation for our dogs. (This may sound excessive to some non-dog-lovers, but Petey and Addie are like our children, without bar mitzvahs or college tuition.) This year, though, we lost Addie in early July at almost fifteen years old, which was a long and good run for a one-hundred pound Labrador built more or less like Shelley Winters in The Poseidon Adventure. She was a big girl whose most remarkable feature was not only her swimming ability, her bottomless appetite, or her love for a stuffed snake called Milton (all of which were considerable): the most astonishing thing about Addie was her ineffable kindness. When we lost her, we were left with her dog sibling, Petey, who is known for a lot of things, but natural, instinctive kindness would not be one of them.

So my wife and I are here in Maine, getting to know this small beast as a separate entity unto himself, while missing Addie. He’s so much younger than Addie and has a lot of crazy herding-dog energy, and every day we walk together for hours on the beach to let him release it. He has never liked water very much — he hates puddles and mud and anything that he has to clean off — but every day he goes in to the water a little bit further, and says hello to more people, like the man we met one morning who was out picking up the giant clams that get washed up when the tide goes out, before the crowds arrived. Petey ran up to him, poking at the pile of beached clams collecting at his feet.

The man stood at the edge of the water, ankle deep in the crashing waves opposite the Seguin Island lighthouse, his arms full of shells. He smiled at us, put them down behind him, and picked up as many of the enormous quahogs he could find. I wondered silently whether or not he was one of Maine’s many stellar chefs who have devoted themselves to the fruits of the state — the produce, the shellfish, the grains — collecting for his restaurant. And then, one by one, he began vigorously hurling the clams back out into the water as far as he could possibly throw them.

“They’re still alive,” he said to me, “and I just hate to see them suffer. It seems so unnecessary, so unkind.”

Petey and Susan and I stood in the surf, watching. We wished him a good day, and then kept going.

The issue of kindness — simple, pure kindness — is one that has been on my mind a lot recently. With the publication of my next memoir Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw, I’ve been asked by many reporters and journalists about my religion, and how I justify it vis-à-vis the fact of my life as an assimilated Jew who does not now and never has had any formal practice. Over and over I have found myself answering that I find religion in the human kindnesses and compassions we show one another every day. In the current climate, that is not easy to find — it seems to be eluding us, whoever we are, whatever we look like, however we vote, and however we pray.

As a memoirist, I often have to write about difficult things that actively involve others, things that perhaps are painful for other people but also directly involve me or have shaped me and made me the person I am. Every time I sit down to write, I ask myself: is this kind? Is this compassionate? Is it fair, or will it hurt someone?

Sometimes I succeed at kindness; sometimes I fail. And when that happens, I have to ask myself about my motivation: what’s the purpose of writing something that is unkind? Is it necessary? Is there another way to tell my story that will not involve someone else’s heart? Often there is; often there isn’t. So what is my policy, my rule?

No matter what, don’t be cruel. No matter what, remember compassion and decency, and remember, as the writer Vivian Gornick said, that “the loneliness of the monster and the cunning of the innocent.” We are all of us human.

We have been walking on the beach with Petey every day we’ve been here: long, ambling strolls in the surf that exhaust him and leave our feet coated with a thick layer of brine. I haven’t seen the clam-rescuer since the first morning we spoke, but every day, I look for him and wonder whether his saving those giant bivalves was for naught — if they got caught in the hands of someone less thoughtful — or they lived another day, safe, surprised, at peace.

Elissa Altman is a food and cookbook editor and the writer behind PoorMansFeast.com, winner of the 2012 James Beard Award for an Individual Food Blog and the foundation for her previous book, Poor Man’s Feast: A Love Story of Comfort, Desire, and the Art of Simple Cooking.

Related Content:

Elissa Altman writes PoorMansFeast.com, winner of the 2012 James Beard Award for Individual Food Blog. A food and cookbook editor and writer, her work has appeared in Saveur and The New York Times, on Gilt Taste and The Huffington Post, and has twice been selected for inclusion in Best Food Writing. She lives in Connecticut with Susan Turner and a small herd of animals.