Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

This piece is one of an ongoing series that we will be sharing in the coming days from Israeli authors and authors in Israel.

It is critical to understand history not just through the books that will be written later, but also through the first-hand testimonies and real-time accounting of events as they occur. At Jewish Book Council, we understand the value of these written testimonials and of sharing these individual experiences. It’s more important now than ever to give space to these voices and narratives.

In collaboration with the Jewish Book Council, JBI is recording writers’ first-hand accounts, as shared with and published by JBC, to increase the accessibility of these accounts for individuals who are blind, have low vision or are print disabled.

Two major epiphanies have forced their way into my life last week, in the most unfortunate way. Still reeling from the heinous attacks committed by Hamas on October 7 – the day with the largest number of Jews murdered since the Holocaust – I look back to my childhood with an unfortunate newfound understanding of the motives behind my parent’s actions.

I am Second Generation, in terms of being Israeli and in regards to the Holocaust. The term Second Generation is well embedded in the historical research of the aftermath of the Holocaust; it describes the unconscious imparting of knowledge that children of Holocaust survivors have been subjected to throughout their lives. However, I prefer to think of myself as a daughter of survivors and a granddaughter of the perished. This, in my opinion, is much more inclusive. It says it all in a mere nine words.

The long shadow of the Holocaust has come to define my life. Like many Holocaust survivors, my parents made every conscious effort to refrain from burdening me with their experiences to me in the course of their life. They wanted me to be a proud and free Israeli which-luckily‑I certainly am. Losing both of them when I was in my forties left me deeply ignorant; I was plagued by the question of how little I knew about my roots. I started researching their whereabouts soon after their passing. As I was in the middle of gathering vital information from relatives and family members, I couldn’t get over the one sentence that kept on cropping up in all the conversations: “I don’t know.”

“What do you mean you don’t know?” I would ask my mother’s niece, herself an Auschwitz survivor, when she failed to furnish me with basic facts about my mom. “We didn’t talk about these things,” she replied. “You are both survivors of death camps,” –(My mom survived Ravensbruck) — “How could you have not?” I admit that my curiosity was harsh. “We were not in the habit of discussing what we went through,” was her reply.

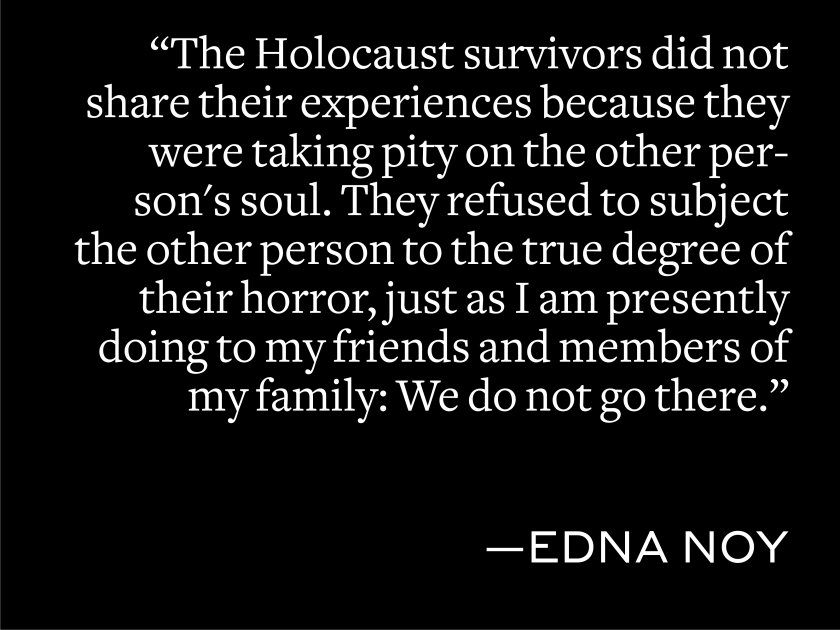

I didn’t think she was evading me at the time, though I did find it odd that close relatives didn’t use the opportunity to support each other by sharing their experiences. The atrocities performed against my people just this week brought forth a fierce epiphany to my life: the Holocaust survivors did not share their experiences because they were taking pity on the other person’s soul. They refused to subject the other person to the true degree of their horror, just as I am presently doing to my friends and members of my family: We do not go there. My heart, for one, is too weak. I am fearing a total collapse, either mine or theirs, so better to keep still.

My second epiphany will be mentioned briefly as it needs safekeeping for purposes of future writing. I will only concede that I was a child who was brutally guarded against real or imaginary wrong doers; over the TV just this week, however, while watching a tearful father confess that he would rather have his eighteen-year-old daughter dead than captured by Hamas terrorists, some of the harshness of my parents’ watchful grip over my sexuality started making sense.

The horrors of captivity are beyond those which we can imagine. We try to guard ourselves and our children from these realities, but to no avail. All we can do now is try to minimize the impact before it is too late. Do everything you can to free our families. Today they are our beloved ones, tomorrow they could be yours. Do not let the captives languish in the dungeons of Gaza for years, do not stay silent like the world was during the Holocaust. If you are at all human, demand the captives be freed at once.

The views and opinions expressed above are those of the author, based on their observations and experiences.

Support the work of Jewish Book Council and become a member today.

A teacher, television host, newscaster and writer, Edna Noy was born in Jaffa in 1950, the only child of Holocaust survivors. Her first novel, All Those Who She Loved, was published in 2008 and was translated into French by the acclaimed Fayard publishing house. Her second novel, The Cherished Daughter, was published in October 2022 and has received many accolades. Edna is presently active in the protest movement against the judicial reform in Israel. She is a mother of three and grandmother of nine.