Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

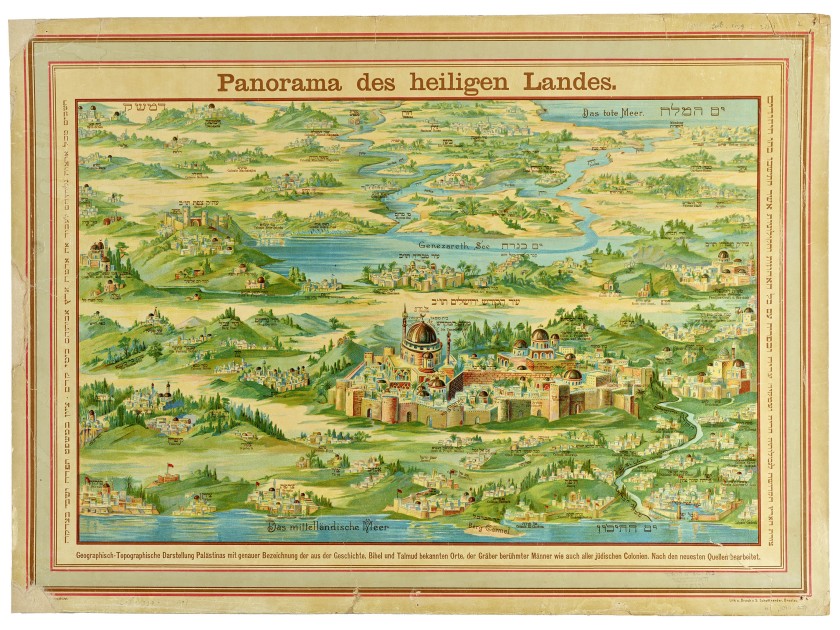

Panorama of the Holy Land (Panorama des heiligen Landes), published by the Salo Schottlaender printing house, Breslau, ca. 1897. The Eran Laor Cartographic Collection. Pal 1134.

One hundred years ago, the head librarian of the Boston Public Library’s West End Branch — a young Russian immigrant named Fanny Goldstein — founded Jewish Book Week. In time, Jewish Book Week became Jewish Book Month, organized by Jewish Book Council. The 2026 issue of Paper Brigade pays tribute to the woman behind JBC with this conversation with the present-day Head of Collections of the National Library of Israel.

The National Library of Israel is older than the State of Israel, but the beautiful building housing its vast and growing collection opened just two years ago, shortly after the catastrophic October 7, 2023 attack by Hamas. In the following conversation, Raquel Ukeles, the library’s Head of Collections, discusses the making of the 2024 National Jewish Book Award – winning book 101 Treasures of the National Library of Israel; the library’s history, mission, and importance to its diverse patrons; and the ambitious, ongoing project the institution took on just days after the library building opened. Titled “Bearing Witness,” this project aims to compile all available oral, digital, and written testimony about October 7th.

Carol Kaufman: When I toured the new building recently, it struck me that it must have been extremely difficult to choose a relative handful of examples to represent the library’s trove of millions of books, documents, rare manuscripts, archives, musical scores, ancient maps, artifacts, and more. Can you describe the process? How many people contributed to 101 Treasures from the National Library of Israel?

Raquel Ukeles: It was quite a challenge. The library has five main collections: Judaica, Israel, Islam and the Middle East, the General Humanities, and Israeli and Jewish Music. The curators of those collections and I began our journey with a day-long retreat to brainstorm about the items we wanted to highlight.

We asked ourselves, “What story do we want to tell people about the National Library of Israel?’ We immediately decided that we didn’t want to produce a catalog and we couldn’t tell just one story. It would have to be a set of great stories — about the writers, copyists, owners, and illustrators of these texts.

We ended that day with a list of over three hundred items. Some are priceless treasures, but others are items on the periphery — those that allow us to tell stories about lesser-known figures and minority communities (such as the Samaritans here and modern Karaites in Egypt). And we wanted to make sure we covered different times and places, and all of the library’s formats.

We decided to organize the book thematically, with the themes designed to elicit curiosity; some of them are traditional library subjects, while others are more whimsical or surprising, such as technology, friendship, and text and power. Using this framework, we succeeded in whittling down the list to about one hundred items.

The book was written primarily by the collection curators. Over forty other colleagues (past and present) also contributed — we have more than fifty staff people at the NLI with PhDs. At a certain point, we realized we’d accidentally written too many essays — 102 — so I cut one of my own. I’m still sorry about it, but retroactively I fell in love with the number 101, because it goes beyond the round number 100 and hints that there is so much more.

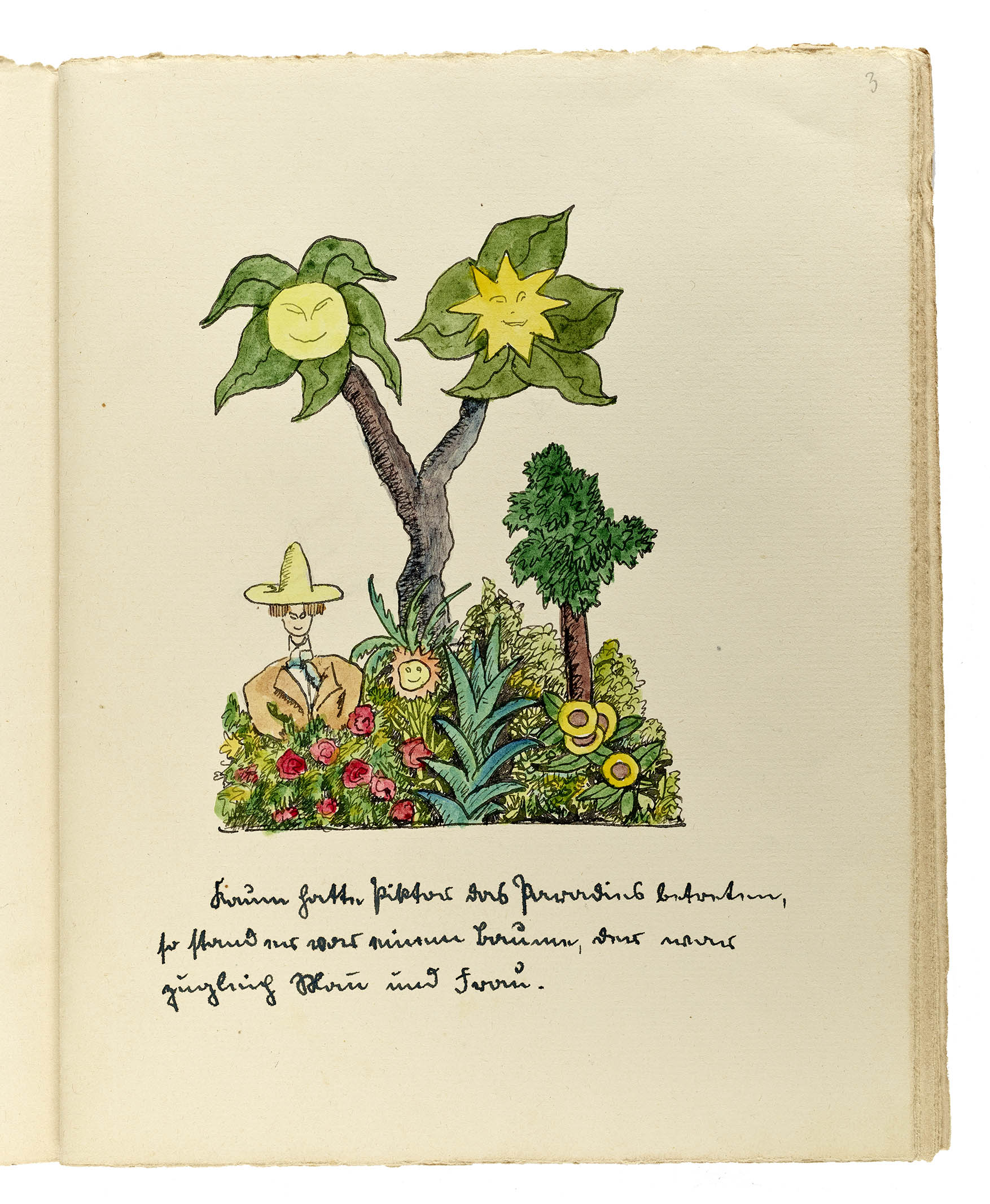

Hermann Hesse, Pictor’s Metamorphosis, 1932 Abraham Schwadron Collection. Schwad 03 08 24.

CK: What are the missions and values embodied in the library, and how are they reflected in the book?

RU: We are the institution for the collective memory of Israel and for the Jewish people worldwide. We also have a mandate of being the premier research institution for the humanities in Israel.

Our objective for the Judaica, Israel, and Music collections is to develop them into the most extensive and significant resources of their kind, ensuring their value for both current and future generations. For the Islam and Humanities collections, our goal is to build world-class resources that effectively support contemporary researchers.

That is, our collections invite local, regional, and global inquiries. 101 Treasures is a tribute to our vision of the library as a kind of laboratory, a place of endless potential that occurs when you put researchers together with rare manuscripts, maps, posters, and even digital material. A library is the encounter between people and material, and the ideas that emerge.

CK: Can you talk a bit about the library’s history?

RU: This institution is 133 years old, older than the State of Israel, and five years older than the First Zionist Congress. One of our “founding fathers” is Dr. Joseph Chasanowich, a physician and bibliophile from Bialystok, Poland. He began collecting books and rare texts, and sometimes accepted books in lieu of payment for his medical services. His dream of a Jewish national library materialized in 1892, and he eventually donated about 30,000 volumes to the Midrash Abarbanel Library, the first public library in Jerusalem.

In 1905, the Seventh Zionist Congress recognized the library as the official Jewish national library, and in 1920, the World Zionist Organization appointed the first professional director, Samuel Hugo Bergmann. Under Bergmann’s leadership, the library expanded its collections and made important acquisitions such as Ignaz Goldziher’s Islamic studies library, which formed the basis of the library’s Islam and Middle East collection, for which I served as curator for ten years.

The library’s history is tightly intertwined with Israel’s. As antisemitism surged in Europe in the years leading up to World War II, Jewish refugees brought valuable archives to the library. After the war ended, the library worked on rescuing Jewish books looted by the Nazis and brought tens of thousands of volumes to Jerusalem. During the 1948 War of Independence, the library’s location on Mount Scopus became inaccessible, forcing the librarians to relocate parts of the collection to ten different places in West Jerusalem. The collections were finally reunited in 1960 when the library moved to a new building at the Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus.

Staying ahead on the technological front has always been critical to our mission. For example, as early as 1952, Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, initiated a project to copy all known Jewish manuscripts worldwide, which became the Institute for Hebrew Microfilmed Manuscripts and is now the online Ktiv Digital Library.

Since 2007, when the National Library Law was passed, the library was transformed from an academic library to a public institution that promotes research, learning, and cultural engagement.

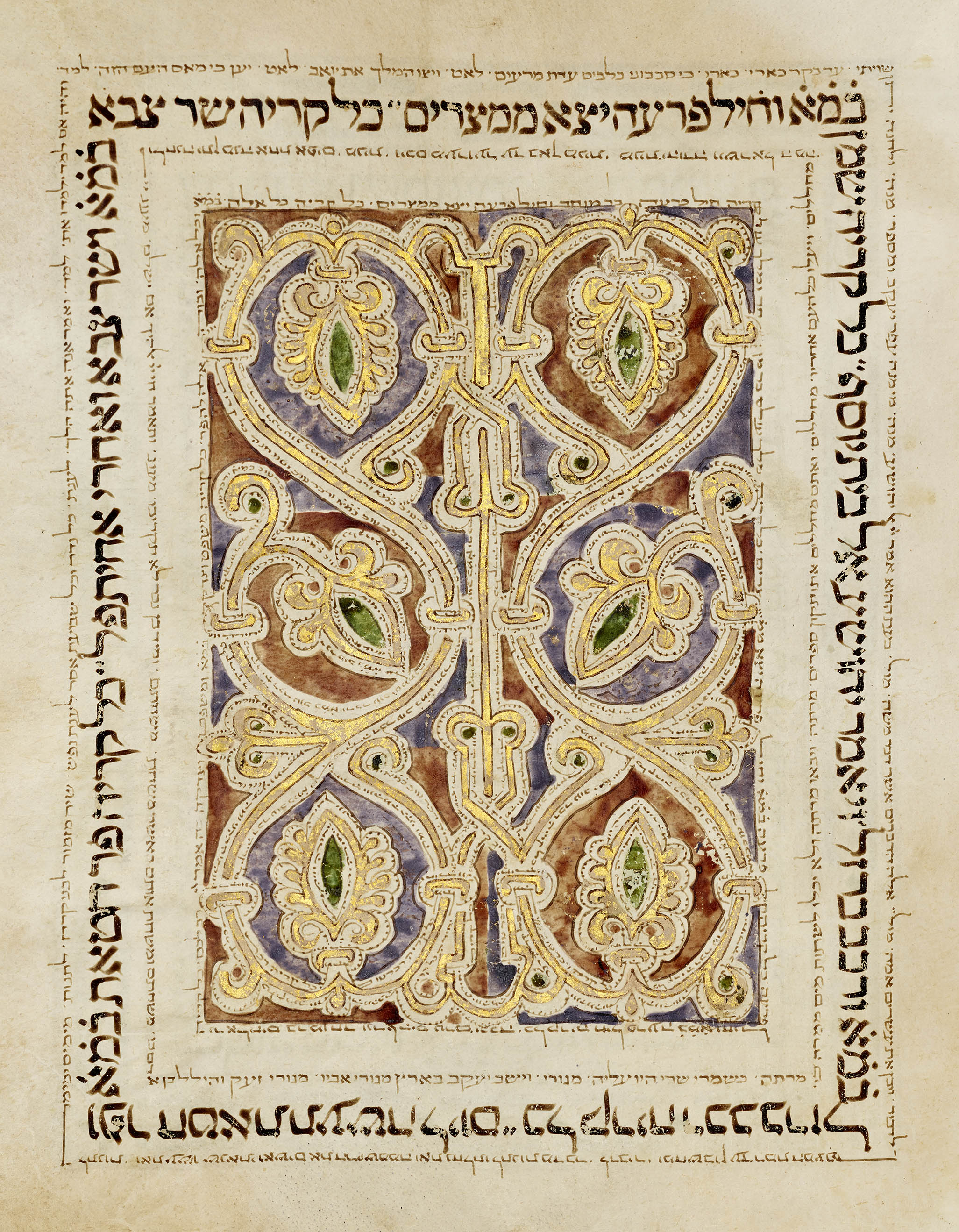

Hebrew Bible with Masoretic notes and Targum Onkelos, Burgos, Spain, 1260. A decorative carpet page separates the Pentateuch from the Prophets. It features multicolor illuminations, gold leaf, micrography, and biblical verses, folio 114r. Ms. Heb. 24° 790.

CK: The new building was slated to open ten days after Hamas’s devastating attack on Israel. The opening ceremonies as well as the book launch for 101 Treasures were cancelled, of course. What was it like for you and the staff at that time?

RU: October 7th was a catastrophic event for everyone in Israel. It affected the library in several ways — first because we were set to open the new building on October 17, 2023. On October 7th, which was Simhat Torah and Shabbat, I was in synagogue. Amazingly, during the air raids on Jerusalem, our CEO and brave colleagues from the conservation department rushed to the library and brought all of the precious original items from the exhibition hall — spaces that had been planned so carefully for weeks, months, and years — down to safety in the underground vaults.

The next day we officially canceled all of the opening ceremonies and braced for war. The question then was, what is the role of this cultural institution in a time of crisis? The answer was that our role as the National Library is to be available for the people. We opened the reading halls three weeks later, on October 29th, and they’ve been packed ever since. I think people are drawn to the library’s architectural beauty, inviting public spaces, and the calm, quiet reading rooms. We are thrilled that the library continues to be a place where all members of Israeli society find themselves and can be found.

CK: Can you discuss the painful, important work the library took on immediately after October 7th?

RU: Over the past year and a half, the library has spearheaded an unprecedented initiative, “Bearing Witness,” to develop a comprehensive collection of materials chronicling the events of October 7th and the period that followed, both in Israel and globally. The goals are to establish a definitive historical account of this pivotal era in Israeli and Jewish history and to create a state-of-the-art archive that will be an essential resource for us now and for the generations to come.

We started to collect material on October 9th, first downloading websites and social media and then expanding to collect oral testimonies, written narratives, WhatsApp messages, video and audio recordings, photographs, and a wide array of religious, cultural, and political expressions. This work has challenged us to develop new methods — real-time collecting runs counter to how libraries usually work. Traditionally, libraries take a long view when collecting and deciding on what’s important to preserve. But there was no time because if you didn’t catch something while it was online, and it got taken down, it was gone. For example, we saw videos posted by Hamas that were removed hours later. So October 7th has spurred us to work in new ways. We’re also collaborating with over a hundred other documentation initiatives. We’ve formed partnerships with grassroots initiatives and cultural institutions in Israel and abroad.

Looking ahead, our emphasis will shift toward establishing a unified archive with shared standards that will enable researchers and the public to work with a single collection. We remain actively engaged in collecting materials, and anyone interested in contributing can do so through the library’s website.

Illustrations prepared for the publication of Wild Plants in the Land of Israel (Tsimhe bar be-erets Yisrael), Tel Aviv, 1960. llustrations and hand-written notes by Ruth Koppel. The Naomi Feinbrun-Dothan Archive. Donated by Uriel Safriel. ARC. 4° 2071.

CK: What was the hardest part?

RU: The hardest part has been the nature of the material, much of which is terrible to see. Another issue is volume — the vast amounts of materials that must be stored before cataloging. To address both challenges, we’re developing AI-based tools that will help to review the most graphic materials and organize the enormous amounts of materials collected.

CK: What are the implications of collecting living history, much of it from electronic media, for scholarly research going forward?

RU: The implications are profound and multifaceted. On the one hand, this collection of primary source material offers unparalleled opportunities for researchers and will enable a richer, and more nuanced, understanding of the events. On the other hand, researchers will need effective search tools in order to navigate these massive archives. Preserving the archives long-term will also require a robust infrastructure and significant resources.

Collecting sensitive personal data raises concerns about privacy. To that end, we have set up a consortium of the main cultural institutions and documentation initiatives, which meets regularly to develop an ethical code for this kind of work going forward.

In short, this is a huge undertaking that will continue for several years and create, as much as possible, the most thorough historical documentation regarding the events of October 7th and its aftermath. And we’re working both within Israel and across Jewish communities internationally, because this narrative extends beyond Israel. It’s a global story.

CK: The new building is truly stunning. What does its design symbolize, and how do you think the architecture influences the ambience of the library?

RU: I feel that the building powerfully symbolizes the interconnectedness of past, present, and future cultural knowledge. The main reading halls were conceived of as a “well of knowledge,” three levels of amply-laden bookshelves that encircle the silent reading halls. At the same time, gathering spaces throughout the building are designed to foster discussion — the deeply embedded Jewish tradition of learning through discourse is integrated into the very architecture. The library has five levels of underground stacks that are accessed by robotic machinery. To me, these silent levels represent a strong foundation in history that supports the upper levels, which are alive with activity — school field trips, concerts, lectures, tours, and more — and symbolize our dynamic present and future. I love how popular we are with teenagers!

Photograph by Yoray Liberman

In essence, the building’s architecture creates a vibrant intellectual hub that is deeply rooted in history but actively engaged in shaping the future. It fosters an environment that encourages both individual contemplation and collective collaboration.

Carol is the executive editor of Jewish Book Council. She joined the JBC as the editor of Jewish Book World in 2003, shortly after her son’s bar mitzvah. Before having a family she held positions as an editor and copywriter and is the author of two books on tennis and other racquet sports. She is a native New Yorker and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania with a BA and MA in English.