Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Background photo by Karim Ghantous on Unsplash

Part of what made the research for Postwar Stories: How Books Made Judaism American so much fun to complete was that I discovered many interesting books from the 1940s. Because Postwar Stories focuses on “middlebrow” literature, many of these titles and authors were popular in their day, but they are not what academics tend to focus on or teach today.

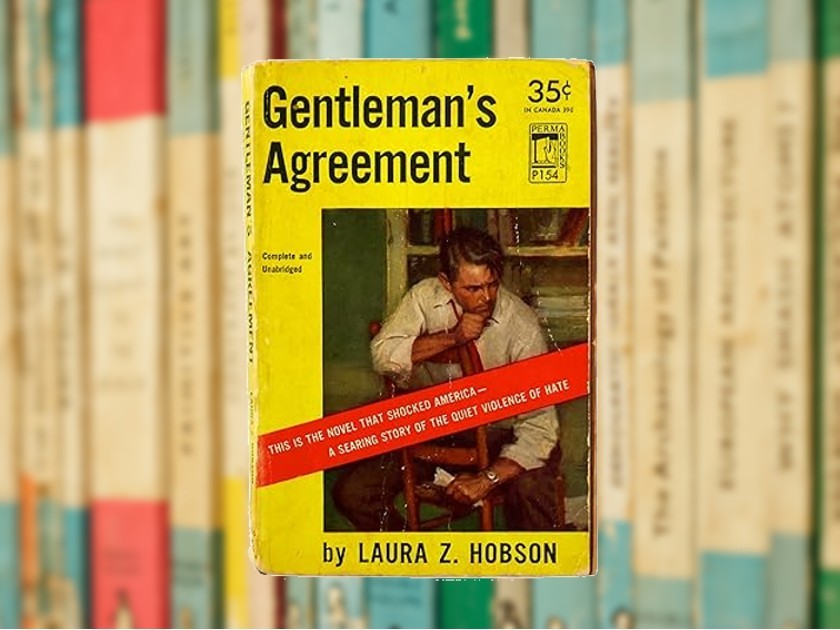

Some of these books fit into the genre I categorize in Postwar Stories as anti-antisemitism novels. These were novels that attacked American antisemitism as un-American. Male writers like Arthur Miller and Saul Bellow also contributed to the anti-antisemitism genre with books such as Miller’s Focus (1946) and Bellow’s The Victim (1947). But the shining star of this genre is Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) by Laura Z. Hobson, whose life turned out to be so fascinating that I am working on a biography of her somewhat surprising life story.

Gentleman’s Agreement was partly inspired by a network of anti-antisemitism novelists, several of whom were women. As I explain in Postwar Stories, Hobson’s discovery of other women writers of anti-racist and anti-antisemitism novels during the 1940s — such as Margaret Halsey’s Some of My Best Friends Are Soldiers (1944) and Color Blind (1946) and Gwethalyn Graham’s Earth and High Heaven (1944) — motivated her to move forward with her own anti-antisemitism novel at a time when even her publisher, Richard Simon, was skeptical of the idea. While Simon tried to discourage Hobson from writing what would become Gentleman’s Agreement, because he didn’t think it was helpful to write about antisemitism, Hobson interpreted the commercial success of other anti-antisemitism novels as evidence that there was a market for the book she was beginning to write in 1944.

Another popular anti-antisemitism novel was Wasteland (1946) by the Cleveland-based Jewish writer Jo Sinclair (under the pen name of Ruth Seid). It’s also known as the first novel with a positive portrayal of a lesbian character. The novel includes scenes depicting the evolving relationship between Jake, a working-class Jewish man, and his psychiatrist. It’s clear, based on the letters readers wrote to Sinclair, that these scenes were enormously helpful to those who might not have known what kinds of conversations were possible with a psychiatrist, or how such treatment could help a person who was struggling with antisemitism in daily life. In the novel, we watch Jake become more comfortable with himself and his Jewish family, largely through the guidance of his doctor and sister. Interestingly, as Postwar Stories explains, the Black writer Richard Wright was one of Sinclair’s biggest supporters. He felt that, with Wasteland, Sinclair had accomplished something new and relevant to all kinds of people dealing with prejudice and discrimination.

The other category of reading material that is central to my book is the “Introduction to Judaism” literature of the 1940s and 1950s. These were magazine articles and books that explained Jews and Judaism to Americans in the immediate postwar years. Similar to the way we saw a surge of reading material and media presentations explaining Islam after 9/11, WWII also shined a spotlight on a group — Jews — about whom most Americans realized they knew very little. After all, this was still a time when many Americans had never met a Jew, and even those who did know Jews from work or school usually hadn’t observed Jewish ritual practices. It was only later in the twentieth century that it became more common for non-Jews to attend bar and bat mitzvahs, Passover seders, Shabbat dinners, and even circumcisions.

Contradicting the swirl of negative images and ideas about Jews that had been circulating in 1920s and 1930s America, anti-antisemitism novels and Introduction to Judaism literature treated Jewishness as normal and American.

But these books and articles were not directed only at non-Jews. As the rabbi-writers of these books and articles understood, many Jews had low levels of Jewish literacy themselves. They needed guides for how to create meaningful Jewish lives as modern Americans. These primers about Judaism included Milton Steinberg’s Basic Judaism, Philip Bernstein’s What the Jews Believe, Herman Wouk’s This Is My God, and Life Magazine articles about Judaism during the 1950s. Postwar Stories describes the making of these books and articles: why particular people came to write books that served to introduce a broad American audience to Judaism. The genre continued to flourish in the late twentieth century, with authors such as Anita Diamant, Rabbi Irving Greenberg, Rabbi Joseph Telushkin, and, in more recent years, Sarah Hurwitz (Here All Along, 2019) and Noah Feldman (To Be A Jew Today, 2024).

Interestingly, unlike the anti-antisemitism genre, which had a fair share of women authors, the mid-twentieth-century Introduction to Judaism genre was almost entirely written by men, reminding us how much religious authority still belonged to men in the postwar years.

Both of these genres — anti-antisemitism novels and Introduction to Judaism literature — were part of a cultural era I call the Midcentury Middlebrow Moment in American Jewish Culture, which lasted from the late 1940s through the end of the 1950s. Many will be familiar with the all-star works that grew out of this period, such as The Goldbergs TV show; the All-of-a-Kind Family children’s book series; The Diary of Anne Frank as a book, Broadway play, and film; and movies like Marjorie Morningstar and Exodus. Like the two genres explored in Postwar Stories, many of these mid-twentieth-century books, plays, and films were different from what came before because of their presentation of Judaism as a respectable American religion. As my book notes, we do occasionally see examples of this kind of middlebrow Jewish culture before the mid century — although more often, Jews were being depicted as an alien immigrant group rather than as members of a respected American religion (e.g., The Jazz Singer). Not until the mid twentieth century do we find such a concentration of middlebrow Jewish culture that reached a mainstream audience.

Postwar Stories brings us into that midcentury world, emphasizing the power of middlebrow literature to instill pride and positive feelings in minority-group members, and to help shift Americans’ feelings about a once-despised people. Contradicting the swirl of negative images and ideas about Jews that had been circulating in 1920s and 1930s America, anti-antisemitism novels and Introduction to Judaism literature treated Jewishness as normal and American. It sounds simple today, but in its moment, it was rather remarkable.

Rachel Gordan is the Samuel Bud” Shorstein fellow in American Jewish Culture at the University of Florida. She received her Ph.D. from Harvard and her BA from Yale.