Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

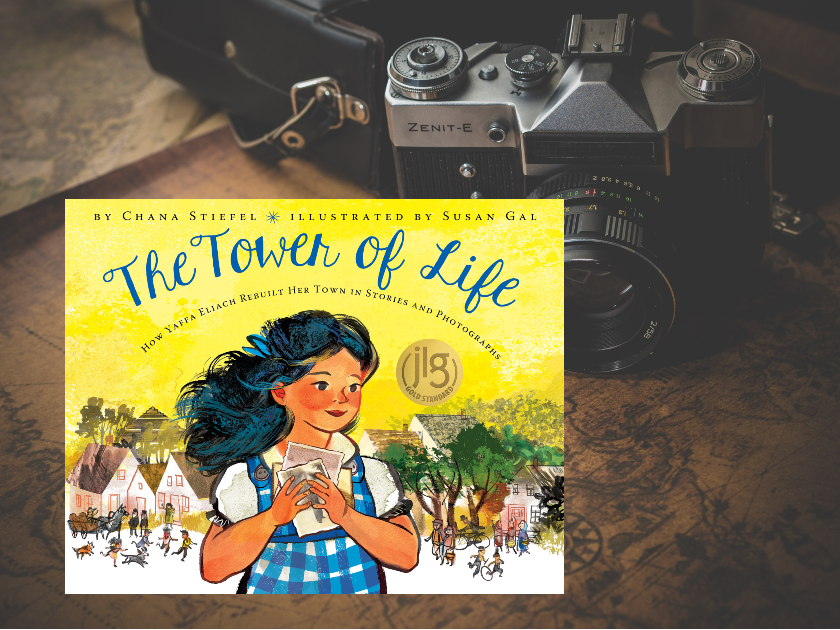

Emily Schneider spoke with Chana Stiefel and Susan Gal, author and illustrator of The Tower of Life: How Yaffa Eliach Rebuilt Her Town in Stories and Photographs. Their new picture book biography of a pioneering Holocaust scholar raises many issues, including the importance of depicting the Holocaust in children’s literature and the relevance of their book to both Jewish continuity and universal human rights.

Emily Schneider: I’m honored to be speaking with you about The Tower of Life, which is an unusual addition to Holocaust-themed picture books. Chana, I’m assuming that you didn’t begin by saying, “I’m going to write a book about the Holocaust for children,” even though that would be a worthy goal. But you must have had a reason for becoming interested in writing about Yaffa Eliach in this way. After all, many Jewish adults may not have heard of her. How did you come up with the idea of writing about a scholar who dedicated her life to chronicling Eishyshok, her family’s shtetl?

Chana Stiefel: I am a children’s book author, and I’ve been writing for about thirty years now. In the beginning, I wrote about science and health; that’s where my background is. But in the last few years, I’ve decided to write Jewish books. I did not set out to write a Holocaust book. Then, in 2016, I opened up the New York Times and found Yaffa Eliach’s obituary. I was riveted. Something drew me to her, and I was inspired by her resilience and hope after all the tragedy that she experienced. She was able to go on with her life and she became a professor of Holocaust Studies. When she was asked to build an exhibit for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, she didn’t want to focus on death and dying and destruction. She remembered her beautiful shtetl, her town, and she wanted to rebuild it. There’s also a personal aspect; my family experienced tremendous loss in the Shoah, as did many other families. Reading Yaffa’s obituary really brought home the message that Holocaust survivors are dying, and it’s our responsibility now to bear witness and share their legacy with the next generation.

ES: Yes, whenever there is a discussion about whether too many Jewish-themed children’s books focus on the Holocaust, this issue of generational responsibility comes up. Your connection to Yaffa’s family made that personal as well.

CS: I’m sure you’re familiar with the word bashert, right?

ES: Yes, when something is meant to be.

CS: There was a lot that was bashert for this book. When I first mentioned to my children that I was thinking of writing a book about Yaffa Eliach, it turned out that both my daughter and son knew her grandchildren. At that time, I was the director of public relations at a Jewish high school for girls called Ma’ayanot in Teaneck, New Jersey. Smadar Rosensweig, who is Yaffa’s daughter and a professor of Bible Studies at Stern College, came to speak. We met and immediately connected over this project. She was instrumental in fact-checking and providing background information. It worked out beautifully.

ES: Susan, your pictures are stunning. How did this project come across your desk?

SG: My agent called me up and said that there was a book and it was “a really good one.” When the manuscript arrived, it just grabbed me. There was a photo of Yaffa as a little girl feeding chickens. And I didn’t have to read any more. I said, “I’m in.” There was something about that little girl that I just connected with. I began to have a real passion for her story. Every book I do, I put everything I have into it. But this book is really special to me.

I had this vision in my head, which became a scene in the book, of generations of families visiting the cemetery and telling stories about who was buried there.

ES: It’s interesting that you were instantly drawn to that photo of Yaffa. Could you explain why you integrated photos and images based on photos into your artwork?

SG: The Holocaust Museum has wonderful archives, so I started gathering pictures. At first, I only studied the photos of the people that were from Eishyshok. I wasn’t reading what had happened to them or who they were. I just wanted to see the imagery. It was really important for me as an illustrator to get the sense of place right, because I had to honor Yaffa’s story, where she came from. As I started looking for pictures from World War II more broadly, I found images of Nazis that reminded me of photos of modern-day Nazis, as in Charlottesville, and I felt a real sense of responsibility. I uncovered more information on Holocaust deniers and became angry. I thought, this book has to come to light. When I said to my agent, “Do you understand that I’m not Jewish? Is that okay?” she assured me it would not matter.

ES: Susan, thank you for mentioning your background. It adds to our discussion, because you clearly approached the book with great empathy, and that is not exclusive to Jewish authors and artists writing about this subject. One way you convey feeling in your pictures is through color. As just one example, some of the violence is not shown explicitly, but rather is demonstrated through the predominant use of reds and blacks.

SG: Yes, when I drew the scenes of destruction in the town, I wanted to honor what happened but also make it a little bit abstract. Often, it’s what you don’t see that can be most frightening. There are bits and pieces, and your brain fills in the rest. I was actually inspired by a painting called “Alabama,” by Norman Lewis, from 1960. He was an abstract expressionist, and his painting is of a Klan rally but doesn’t explicitly show violence. As I was drawing the Nazis, I looked at the black-and-white images, and I blurred my eyes to get rid of any features. I wanted to keep them as dark silhouettes. The Nazis didn’t deserve to be shown with features, so they are featureless.

ES: As I look at the pictures and listen to Susan’s comments, I’m reminded of how perfectly the text and pictures work together in the book. Chana has had to truthfully address death and destruction, choosing to use certain words and avoid others; Susan has had to make those same choices in her images. Chana, at one point you use the word “uprooted” rather than “destroyed.” When you’re writing about the Holocaust for younger children, it’s a difficult balance. You have to be honest about the horrors, but also allow a sense of awe, sadness, and pride in people like Yaffa.

CS: Yes, in a children’s picture book every word has to be carefully chosen. I had this vision in my head, which became a scene in the book, of generations of families visiting the cemetery and telling stories about who was buried there. I was thinking about the roots of trees and how there are many comparisons of Judaism to a tree of life. There was community in Eishyshok and throughout Europe for 900 years — until the Nazis came, and then it was uprooted. I was hoping that Susan would find a way to show that uprootedness, and she certainly did. One theme in the book is how the composite of light and life captured in time is in essence a photograph. Yaffa’s grandmother was the town photographer. Yaffa’s parents taught her how a glimmer of light can chase away darkness. On the cave wall, when Yaffa is hiding with her family, there are Hebrew words in my handwriting: tikvah, or hope, ohr, meaning light, chayim, for life, and shalom, peace.

ES: Susan, another remarkable scene is the two-page spread where people from the village stand behind simulated documentary photos. It’s inventive, somewhat humorous, and looks lovingly at the past without too much nostalgia. How did you come up with this idea?

SG: I had all these layers of artwork on my computer, and as I started to render the people, I decided that I wanted them to be looking at the reader, to be validated, to say that they existed. Of course, they all were murdered. But I thought, the pictures become the person. The pictures come to life. They are looking out at you.

ES: You both made the point so eloquently about the urgency of teaching children about the Holocaust. The people in the photographs, and others like them, are nearly gone. What would you like readers to take away from this book?

SG: I grew up learning about the Holocaust in elementary school. Someone’s grandmother came to our class; she had been in one of the camps. She had a tattoo on her arm. We saw pictures of people as stacks of bodies. It was something that happened a long time ago. But these people also had vibrant, wonderful, rich lives, which I think is important. That’s a connection that we can make to the present day. I just feel really blessed to be the illustrator of this book.

CS: If you’ve ever been to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, you’ve probably noticed that not everyone who visits there is Jewish. As a Jew, I find it hopeful that people want to learn this history. You cannot leave there without feeling moved or changed. Yaffa said that when people look at these photographs in her exhibit, they see themselves. We need to teach children history and we need to develop empathy. We’re not the same, but we’re all human. We definitely need books about Jewish joy and Jewish life and the Jewish diversity, but we cannot forget our history.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.