Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

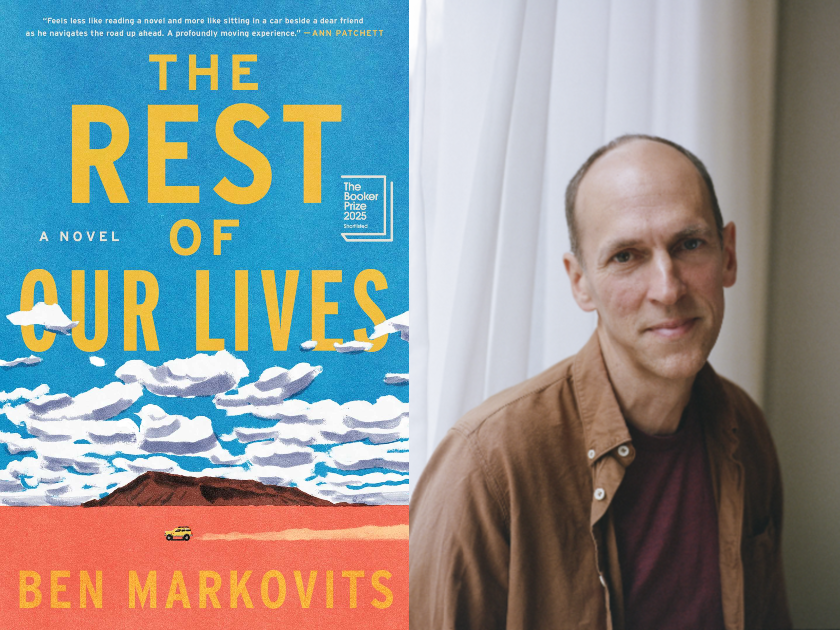

Author photo by Kat Green

Shortlisted for the 2025 Booker Prize, Ben Markovits’s stunning new novel, The Rest of Our Lives, takes readers on a road trip across the US, reckoning with change, love, and uncertainty. Jewish Book Council spoke to Markovits about crafting this novel, the American road trip canon, and how his own unexpected life experiences informed the work.

JBC: On the first page of the novel, Tom describes his wife as an unreliable narrator of her life: she is “a person who tells stories about her motives and actions, which are very persuasive … so it’s sometimes hard to talk about or even work out what’s really going on.” Could Tom, the narrator of the novel, be described in the same way? What do you see as his real identity versus the impression of himself that he wants to give to the reader?

Ben Markovits: This is hard to answer. I guess I would say that Tom is less likely than Amy to “tell stories about his motives and actions,” less likely to come up with theories about them, or excuse himself because of some hard-to-pin-down connection or cause … but he’s also less likely than Amy to admit that he’s wrong, because he’s so attached to his idea of himself as someone who sees things accurately, which is part of his problem.

JBC: The Rest of Our Lives is structured around a road trip through America. How does Tom’s geographical journey mirror his emotional one?

BM: Toward the end of the novel, Tom quotes something his father said to him once, when Tom and his kid brother visited him in Los Angeles, after his divorce. He takes them to the beach and they go swimming in the ocean: “Your first taste of the Pacific.” It’s a phrase Tom remembers, maybe because it seems to represent for his dad the idea that you can have some kind of larger freedom, by leaving your wife, but also by heading West, starting again in California. That might have been Tom’s idea, too, when he set off, but in fact his road trip leads him inward as much as outward, and his options seem to narrow around him as he gets sicker. His only real taste of some other possibility happens when he stays with his ex-girlfriend in Las Vegas. He imagines another future and another life, but it mostly fills him with fear, or even horror, at the way you can alter yourself — partly in reaction against his father, and what his leaving did to their family.

JBC: How do you see The Rest of Our Lives in relation to the canon of American literature about road trips? From your perspective as someone who has lived in different countries and now lives abroad, is there something about the road trip that is particular to American identity or imagination?

BM: To answer the second question first, yes! America is so much larger than the other countries I’ve lived in (Germany and England), with so much more open space, that the road trip does seem to promise possibilities of starting over that seem particularly American.

I love a lot of road trip novels (On the Road, of course, Independence Day, etc.), or even novels that promise road trips that never quite happen (like Rabbit, Run), but I’m also a fan more generally of stories in which characters try to opt out of their lives and start again — like Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, or Laurie Lee’s As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, or Ann Tyler’s Ladder of Years.

JBC: I’m fascinated by how Tom sees traditional societal roles — in terms of marriage, gender, family, etc. — changing around him. Could you talk about his decisions to ignore/repress these changes or confront/accept them?

BM: I suppose part of what depresses him is the feeling that he’s supposed to shut up about certain things, because his views are too old-fashioned (in a liberal way), but he’s also supposed to keep quiet when other people confront him with the problems of their modern lives … But I think he’s suspicious of his own past, too, and his own views, and feels like maybe it’s just as well he doesn’t have much of a voice anymore — it’s almost a relief to give it up.

America is so much larger than the other countries I’ve lived in (Germany and England), with so much more open space, that the road trip does seem to promise possibilities of starting over that seem particularly American.

JBC: You write across many genres. How does your nonfiction and poetry inform your fiction and this novel in particular?

BM: When I was younger, I mean like a teenager, I wanted to be a poet. The kind of poems I wanted to write were the ones that in my old nineteenth century editions would be collected under the title “Occasional Pieces” — poems written on anniversaries, to accompany a birthday present, or to celebrate the last day of school, etc., some small scale local event that matters to a small circle of people and which the poem is supposed to commemorate. Later I realised that the novel was a very good form for writing about these sorts of events. The nonfiction I write (mostly memoir‑y essays, I guess) helped me to get a feel for the way I would describe something if it was actually true — which turns out to be also the way I’d like to describe it in fiction. I wanted The Rest of Our Lives to feel almost like a memoir, even though of course it isn’t.

JBC: How did your own unexpected health issues inform or alter the novel?

BM: My cancer changed the book a lot. Before I got sick, I was planning to make the ending much colder. My original idea went something like this: that Tom’s problem is he thinks he hasn’t done anything wrong, and he’s clinging to that notion, even if it’s damaging his marriage and his life. Then I was going to push him, as a way out, into some kind of wrong-doing (you can still see the seeds of it in the published version), but instead of offering a solution it would leave him feeling completely abandoned by the end, and deserted even by his own sense of himself.

Then I got sick and realised a couple of things. The first was just that, well, when things that matter happen, the feelings that matter tend to rise to the surface. In this case that meant Amy’s real love for Tom, Tom’s for her, and his kids’ devotion to him, too. It was obvious to me that he would not be abandoned. But I also realised that I was never going to be able to get him to do the thing I had in mind for him to do anyway. Partly because he was too nice, but also because he already felt too defeated.

JBC: What was the process like of crafting this novel? What drew you to the road trip structure?

BM: I wrote the first couple of pages one afternoon when I was actually in the middle of working on something else. The first line occurred to me, and I just sat down and started writing. Later, I came back to it and saw in those pages a few things I could work with, including the idea that the novel proper might start when he drops his daughter off at university and has a chance to put to the test his resolution to walk out on Amy. My guess is (I don’t really remember) that the road trip idea came to me then. It’s a way of turning a novel about the breakdown of a marriage into something a little more fun. It also gave me (and my family!) an excuse to go on a road trip, which we did one summer, even while I was getting sicker — driving from Austin to California over three wonderful weeks, one of the best family holidays we ever took.

JBC: What are you reading and writing now?

BM: I’m editing a draft of my next novel, a sort of counterpart to The Rest of Our Lives—about the other end of marriage, the beginnings, told from the point of view of the wife. And I’m reading (or rather, I just finished) a novel called Seven by Joanna Kavenna. It’s a kind of philosophical road trip, very beautifully written and funny, too.

Becca Kantor is the editorial director of Jewish Book Council and its annual print literary journal, Paper Brigade. She received a BA in English from the University of Pennsylvania and an MA in creative writing from the University of East Anglia. Becca was awarded a Fulbright fellowship to spend a year in Estonia writing and studying the country’s Jewish history. She lives in Brooklyn.

Simona is the Jewish Book Council’s manager of digital content strategy. She graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with a concentration in English and History and studied abroad in India and England. Prior to the JBC she worked at Oxford University Press. Her writing has been featured in Lilith, The Normal School, Digging through the Fat, and other publications. She holds an MFA in fiction from The New School.