Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Earlier this week, I reflected on being a twenty-first-century Jewish author engaging with Shakespeare. It’s a topic that shapes my relationship to my new Shakespeare-themed novel, Juliet’s Nurse. But there’s another question that I only began to consider after the novel was finished, and I began to speak about it at gatherings of Shakespeare scholars: how did Shakespeare himself engage with ideas of Jewishness?

It might seem like Shylock in The Merchant of Venice is the place from which to answer that question, as many critics have done. But the image of the Jew appears in other Shakespeare plays as well, although they include no Jewish characters per se. Instead, Jews are invoked to represent a particular idea of difference.

Launce, a clownish character in Two Gentlemen of Verona, complains his companion Crab, “has no more pity in him than a dog. A Jew / would have wept” when Crab did not. Although it might seem that Launce’s hypothetical Jew compares favorably to Crab, the allusion is meant to show that even a Jew would weep, implying that Jews are generally less able to display the full range of human emotions. And if the imagined Jew does better in the human empathy department than Crab, it is only because Crab is literally a dog, and not a person. The belief that Jews possess a less-than-admirable nature is reinforced later in the play, when Launce seeks a human drinking buddy. He implores Speed, a fellow servant, “If thou wilt, go with me to the alehouse; if / not, thou art an Hebrew, a Jew, and not worth the name / of a Christian.” That’s peer pressure late-sixteenth-century style: bottoms up and drink it down, or you’re as unworthy as a Jew!

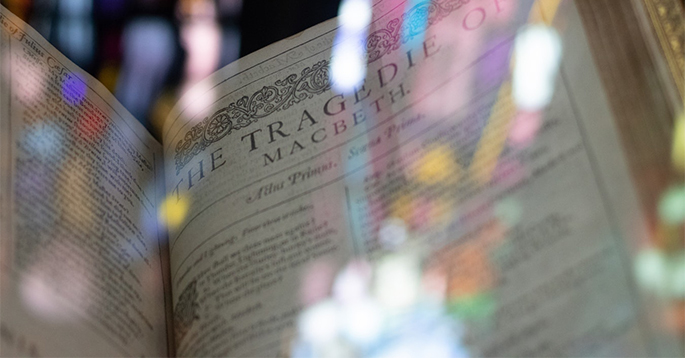

Although Launce is meant to be a laughable character, his characterization of “a Jew” is reiterated by a range of Shakespeare’s other characters. In Macbeth, one of the witches describes the contents of their bubbling cauldron in a way that mixes the animal, the supernatural, and the ethnic other:

Scale of dragon, tooth of wolf,

Witch’s mummy, maw and gulf

Of the ravined salt sea shark,

Root of hemlock digged i’the dark,

Liver of blaspheming Jew,

Gall of goat, and slips of yew

Slivered in the moon’s eclipse,

Nose of Turk, and Tartar’s lips …

Taken line by line, the description is significant. Turks and Tartars are also cast as dangerously magical outsiders because they don’t fit within normative Christian identity. But it’s only the Jew whose errant status is underscored by the description of “blaspheming.”

Perhaps because Jews were perceived in terms of blasphemy, to call someone (even yourself) a Jew became a stand-in for an accusation of false oath-taking. Much Ado About Nothing is a sort of Renaissance rom-com in which the two main characters insist they hate each other, until they are tricked by their friends into revealing that all their bickering is actually a cover for mutual adoration. When Benedick finally declares his true feelings for Beatrice, he says, “if I do not love her, I am a Jew.”

This use of “Jew” as an indication that someone is swearing falsely is repeated in Henry IV, Part I, when the buffoonish Falstaff exaggerates his bravery and prowess during a recent violent encounter. He claims to have subdued a large number of opponents, contending, “they were bound, every man of / them, or I am a Jew else: an Ebrew Jew.” The fact that Falstaff is lying only complicates the strange equation of prevarication with Jewishness. The audience, and even the other characters Falstaff is addressing, know that he didn’t perform the amazing feat he insists he did, yet it’s also clear that Falstaff is not actually a Jew.

So what are we to make of the way Shakespeare invokes the figure of the Jew across his plays? What does it tell us about how Jewishness was perceived in Renaissance England?

The answer may seem counterintuitive: these references, and ones like them found in the writing of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, may tell us less about the author’s and the audience’s perceptions of Jewishness than about their perceptions of Englishness. (This may be easier to understand if you consider some more recent analogies. Through much of the twentieth century, concerns about “Communists” were voiced in ways that were meant to encourage, or even coerce, certain types of behavior on the part of “red-blooded Americans.” Similarly, from the nineteenth century on, representations of “blackness” by white writers and performers in the U.S. often reflected much more about the anxieties of whites than about the reality of blacks.)

James Shapiro, a professor at Columbia University and author of Shakespeare and the Jews, asserts that if we examine what Shakespeare and his English contemporaries wrote about Jews, we can discover the cultural anxieties they felt about their own Englishness during a period of “extraordinary social, religious, and political turbulence.”

That turbulence was rooted in events occurring decades before Shakespeare was even born, most notably King Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church and the subsequent creation of the Church of England, which demanded a shift in religious affiliation across the nation. The enormity of this change is difficult for us to comprehend. So much of life in the era was defined by religious practice, and that practice was unquestionably Catholic — until suddenly it wasn’t. And then, during the reign of Queen Mary, the Catholic daughter of Henry VIII’s first wife, the practice of Catholicism became acceptable again, and Protestants were subject to persecution. But only until Mary died and was succeeded by her Protestant half-sister Queen Elizabeth I (during whose reign a certain young playwright first made a name for himself) were Protestants politically dominant again.

If you’re having trouble tracking all those religious switcheroos, imagine how it must have felt to live through them. Particularly when other European countries pursued everything from royal marriages to outright war as they vied for political and religious alliances with England.

But what was happening to Jews themselves, as England swung back and forth between Catholicism and Protestantism? That’s a more hidden part of the history. Jews were banned from England in 1290, and not officially readmitted until 1656 (and even then, they could reside in England but weren’t granted full citizenship). But despite the ban, there was a prevailing uncertainty about whether Jews remained in England. And, as the centuries passed, there was concern about Jews from other parts Europe entering the country, as began to happen in the wake of Jewish expulsion from Spain and Portugal.

Unlike groups defined by nationality, Jews might shift their geographic presence; but “Jewishness” also implied a different kind of potential instability. In countries under the Inquisition, suspicions persisted regarding whether conversos, Jews forced to convert, were secretly maintaining their Jewish identity and practices. In England, there was a strangely inverse fear that Catholics might be infiltrating the country by disguising themselves as Jews. And throughout Europe, as part of the immense rift begun by the Protestant Reformation, some Catholics accused Protestants of being too like Jews in their practices and beliefs — and some Protestants alleged the same about Catholics.

All of this meant that to be a Jew was to be not English — and vice versa. But at the same time, notes Shapiro, there was no easy way to distinguish Jews from either Protestants or Catholics. Consider all the Shakespeare passages alluding to Jews: they seem to insist that “a Jew” is inherently different from, well, everybody else. But the playwright doth protest too much, methinks — the compulsion to cordon off Jews and insist that they were different might in fact suggest just the opposite. Falstaff, after all, does swear falsely, without being a Jew. If anyone might be a Jew (or become one), what did that mean for Englishness, given that Jews were categorically not English?

Of course, the construction of an imaginary “Jew” in writings by Shakespeare and his contemporaries must have affected attitudes toward real Jews. But exploring the cultural, political, and religious contexts in which Renaissance English representations of Jewishness were formed is important for understanding what was at stake in Shakespeare’s writing about Jews.

Read more about Lois Leveen and her work here.

Related Content: