Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

From How I Learned Geography by Uri Shulevitz, published 2008

In a recent profile on Publishers Weekly, illustrator and author Uri Shulevitz wryly commented, “I think I have earned the right to call myself an old man.” The celebrated eighty-five-year-old artist’s illustrated memoir, Chance: Escape from the Holocaust, is just out and already being received with great acclaim. Born in Warsaw in 1935, Shulevitz escaped Nazi-occupied Poland through the Soviet Union, eventually settling in Israel; he moved to the US in 1959, where his career as an author and illustrator flourished. His many honors and awards include the Caldecott, Sydney Taylor, and National Jewish Book Awards. Like the medieval explorer in his The Travels of Benjamin of Tudela, Shulevitz has delivered on his promise to bring Jewish life — in both its fantastic and most mundane events — to readers: “So I’ll tell you only about the most amazing places I saw and the most fascinating stories I heard.” His latest book, Chance, looks back at the past and illuminates the motivation behind many of his earlier Jewish-themed works. Three stories in particular—How I Learned Geography, Benjamin of Tudela, and The Magician—richly illustrate Jewish responses to the deprivations and the joys of a precarious world.

How I Learned Geography (2008)presents an event in young Uri Shulevitz’s life which he later revisits in Chance. As in folk or fairy tales where a character — often a child — receives something of little material value which later turns out to be redemptive, Uri’s father brings home to his family a seemingly useless map of the world. Chance traces the Shulevitz family’s odyssey from Warsaw to Belarus, Siberia, Kazakhstan and Paris, as they struggle to stay alive while evading Nazi terror. What is it about this particular episode that compelled the author to return to it in the context of a longer memoir?

In Geography, the voyage is telescoped into one brief moment: “When war devastated the land, buildings crumbled to dust. Everything we had was lost, and we fled empty-handed.” Uri’s father leaves to find food in the market, a crowded bazaar of exotically dressed people speaking unfamiliar languages. His quest for food is located within the Jewish experience of flight from persecution and refuge — in this case, the Central Asian steppe. He returns not with bread — which cost too much — but with a carefully rolled-up map. An oversized suit hangs off his gaunt body while Uri and his mother hold out their hands like beggars. Uri’s parents each play a distinct role in his life. Yet they also fulfill one typical image of a Jewish home, where a strong and pragmatic woman’s quest to protect her child is frustrated by a male dreamer. Angered at her husband’s inane logic that, since they were unable to afford food they might as well admire the map, she translates his failure into mocking words: “’No supper tonight, Mother said bitterly. ‘We’ll have the map instead.’” Uri is angry, too.

He returns not with bread — which cost too much — but with a carefully rolled-up map.

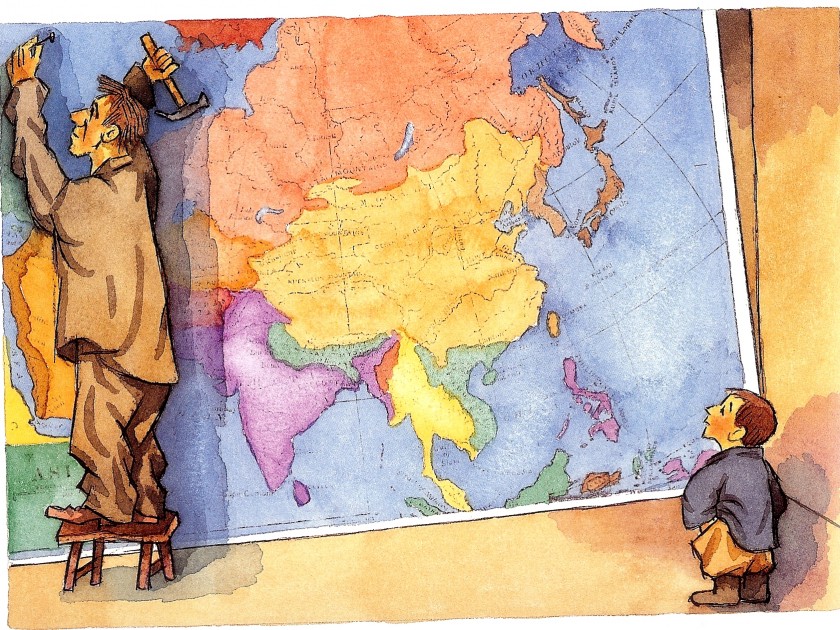

In both books, the map becomes a magical reminder that, even as his family is trapped by circumstances, the world outside is limitless. The picture book’s two-page spread of father and son connecting wordlessly with one another through the enormous map has a tone of reconciliation. Interestingly, How I Learned Geography is dedicated to the memory of his father, the man who stands on a small stool in one corner of the first picture, patiently mounting the map on the wall. Uri, a small boy dressed in grownup male clothes, watches. In the next picture, he is alone with the map, concentrating intently as he draws pictures based on its content “on any scrap of paper that chanced my way.” Chance has governed his family’s escape, as well as his ability to practice his art. The following pages show Uri flying through the air over the map, like Marc Chagall’s shtetlJews, transcending his physical world through imagined possibilities.

The Travels of Benjamin of Tudela follows a journey through actual time and space. Based on the journal of a twelfth century Spanish Jew who explored the world more than a century before Marco Polo, Shulevitz’s illustrated book for older readers places one wandering Jew at the center of world events — the perennial outsider looking in. Each page features dramatic images from history, some involving Jews directly, others only peripherally. The colorful map of Shulevitz’s childhood is no longer an invitation to dream, but a background to a series of intensely realized moments. The city of Constantinople features a spectacle of wild animals in the Hippodrome, while Benjamin comments that Jews are confined to an outlying area of the city. In Jerusalem, the Jewish traveler mourns the fact that Christian Crusaders control the city, and in Baghdad he conceals his identity by speaking Arabic and following Islamic customs.

Each page features dramatic images from history, some involving Jews directly, others only peripherally. The colorful map of Shulevitz’s childhood is no longer an invitation to dream, but a background to a series of intensely realized moments.

The shape-shifting Benjamin observes from the sidelines, but also immerses himself in the Jewish past. Pictures change tones, from the dark brown of shifting sands in the Sahara, to the riotous blue of waves off the coast of Sicily. Among the Jewish community of Baghdad, he hears stories of legendary Jewish warriors in Arabia, “the only Jews who live in freedom, in their own land, and have no foreign ruler.” In Egypt, Benjamin claims to recognize the storehouses for grain that the biblical Joseph had built, proving his irreplaceable value to the ruling Pharaoh although he had arrived in the land as a slave. Everywhere that Jews lived marginalized lives, they might also rise to positions of influence or power — reliant on chance, of course. As in Shulevitz’s vulnerable childhood, they might survive.

The Magician is a quieter and more poignant tale; Shulevitz translated and adapted it from a Yiddish story by I.L. Peretz. In this book, the central characters are a poor couple rooted in a small town. The magician himself, the prophet Elijah in disguise, is the traveler, appearing suddenly to resolve the terrible poverty of a man and his wife who are too poor to make a Passover seder. The magician’s tricks are so elaborate and his ragged appearance so contradictory that the couple remains skeptical. They visit their rabbi to ask if the magic is good or evil. Shulevitz’s small and detailed black and white pictures are spaced out, leaving inches of white background between the text at the bottom of the page and the image above. Facing only a wooden table and glowing candles, the magician pulls food, wine, and pillows from the air, allowing them to float downwards and assemble themselves exactly as needed.

The couple’s patient humility has been rewarded, but the rabbi’s explanation also supports Shulevitz’s own experiences: “Evil magic cannot create real things. It can only fool the eyes.” The enchantments of Uri’s paper map, the incredible visions of Benjamin of Tudela, and the magician’s perfect creation of a seder meal, all testify to imagination’s power. None of these books’ protagonists can alter the conditions of their chaotic and hostile world, but they construct a parallel reality of Jewish existence and joy. In introducing his account, Benjamin asserts that he will try to narrow its focus so as not to overwhelm the reader: “So I’ll tell you only about the most amazing places I saw and the most fascinating stories I heard.” Uri Shulevitz has fulfilled his character’s promise in a long and remarkable literary life.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.