Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

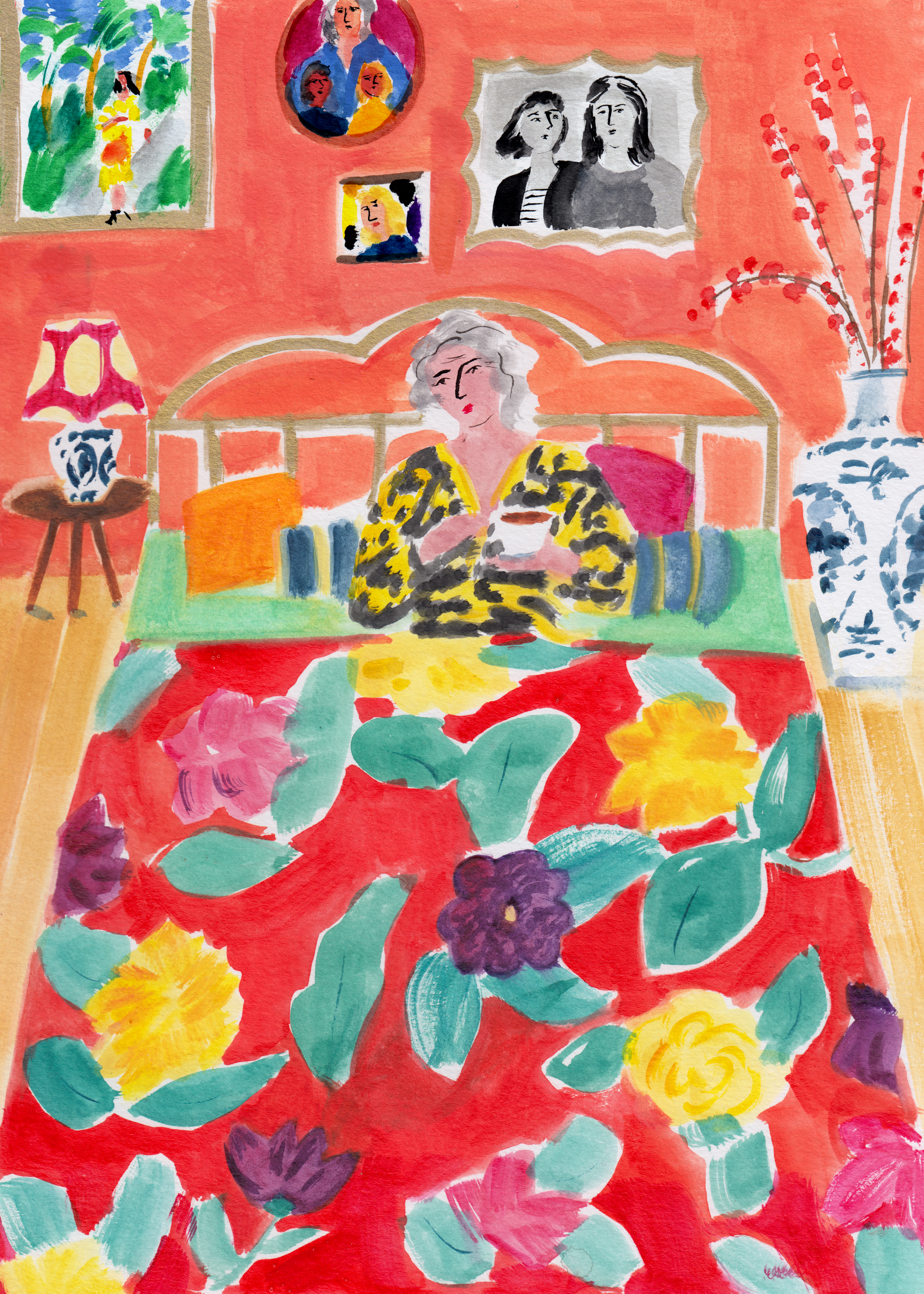

Ilustration, cropped, by Laura Junger

“Gram, some guy’s here.”

Frances put down her corned beef sandwich. Russian dressing dripped down her chin.

“You got some schmutz there.” Josie handed her grandmother a napkin from the stack on her desk. Frances had gotten them monogrammed when she first started in the business: FPA for Frances Perlman Abraham. In red letters. The shade matched the Revlon lipstick on the ends of her cigarettes. The suit she wore on her first trip to New York City to buy merchandise for the store. And her rage when her ex-husband started dating a Hungarian knockout and invited their old friends—her friends — over for bridge and cocktails to witness the bliss of his new life. What did Ira know from cocktails, anyway?

“What guy? Tell whoever it is I’m busy.”

Josie blew a bubble the size of her head and popped it with her index finger. Sometimes, Frances wondered why she’d hired her youngest granddaughter. She loved Josie, of course, maybe even more than the other grandkids, but lately, the girl seemed lost. Last week, she’d shown up late on Saturday — Frances’s busiest day of the week — wearing sunglasses and smelling like she’d bathed in booze. Frances had sent her straight home and told her not to come back until she’d showered and put on a fresh blouse. Imagine what the customers would think. She could see the headline in The Detroit Jewish News: “Frances Abraham Employs Drunk Teen.”

“Yeah, I told him. He won’t leave. He says he knows you. Sol Goldman. Or Goldfarb, maybe?” Josie shrugged. “Something Jew‑y.”

Frances stood in the doorway of her “office,” which was really a windowless storage room at the back of the store. Her small, square desk, just big enough for her ashtray and fax machine, faced the wall closest to the showroom. The rest of the space wasn’t much to look at: boxes of invitations and stationery piled up to the ceiling. Fluorescent lights flickering overhead. Smoke from her cigarettes lingering in the air. Some customers commented about the smoke, but this was her store, wasn’t it? Her castle, her rules. There he was: picking through the birthday cards she’d neatly arranged in wooden holders along the perimeter wall. And putting them back in the wrong spot, of course. He moved from the birthday section to the display table at the center of the room. Holding up a sterling silver picture frame, he squinted at the price tag.

Sol Goldstein. Frances had known Sol and his wife, Nadine, for years, back to their Central High School days. Later on, they had raised their children in the same neighborhood in Northwest Detroit, where all the Jewish families lived at the time. Where there were always kids chasing each other in the streets and it didn’t matter which house they ran into. All the parents knew each other and, at least in her more halcyon memories, they were most likely playing a game of rummy or mahjong on the front porch.

The Goldsteins used to come over every so often for bridge. Nadine was a lovely woman, but a lousy player, and Frances played to win.

Do you always have to go for the jugular? Ira had said. I’m surprised they come back here when you make Nadine feel so stupid.

I don’t make her feel anything. She is stupid when it comes to the game. Why should I dumb down my playing just because she doesn’t know Stayman from a Jacoby transfer?

It’s just a game, Fran. You take all the fun out of it.

She knew that what he meant was: You take the fun out of everything. It would be hard to point to one moment, one fight, that had broken them in two. The crack between them had widened over time, because of little things and big ones, until, even when they were together in the same room, they each felt alone.

Nadine was one of the only people to call and ask how she was after the divorce. Frances had admitted how lonely it was to eat in front of the TV with only her box set of Hercule Poirot videos to keep her company. So Nadine had suggested that they meet for dinner. For the first six years of Fran’s single life, they’d go out now and then, whenever Sol went away on a business trip. But then, she’d died. Just like that, in her sleep.

Hard to believe it was now 1992. Nearly a decade had passed since she and Ira had called it quits, eight years since she’d opened the store, and four since they’d shoveled all that dirt onto Nadine’s casket. Fran had barely spoken to Sol since the funeral. They always exchanged a quick hello in the temple’s atrium on Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur, the only occasions she went to services. But without Nadine and Ira, both more gregarious than their spouses, there wasn’t much holding the friendship together. Seeing him in her store now, she felt a twinge of regret that she had never checked in on him, the way Nadine had with her.

She walked toward him.

“Fran, you don’t know how happy I am to see you.” He took off his Tigers cap. They were both nearing seventy, but Sol had looked like somebody’s zayde for as long as she could remember. He’d gone bald early, when they were still in their twenties, and the hat had become his signature look. Beneath the bill was the prominent port-wine stain on his forehead, which reminded her of Gorbachev’s. Sol had never been handsome, especially compared to Ira, but he had something else — a way of making a person feel that they mattered.

“Me too, Sol. How’s the family?”

“Everyone’s good, kenahora pu pu pu. I have six grandchildren now, would you believe it? And my little Anna — well, she’s not so little anymore — she finally met someone. That’s why I came in.” He looked down at his shoes, pulled a handkerchief from his pocket. “When our older kids got married, Nadine picked out the invitations.”

“Say no more, Sol. I’m sure we can find something beautiful for the occasion.”

“You always had such great taste. Nadine used to say, ‘I wish I could make our house look like Fran’s.’”

The house on Outer Drive was exquisite. Before she married Ira, she had dreamed of being a fashion illustrator. At eighteen, she’d even taken classes at Wayne State University downtown. The professor brought in models wearing the latest styles from Hudson’s. Frances would sketch them with a pencil, then bring them to life with watercolor. The instructor said she was a natural. She should get out of Detroit and go study at Pratt in New York. She imagined living in a tiny apartment with a big oak desk for her paper and paints. Gallivanting around the city with other artists and creative types.

But who had the money for all that? Her father had been a bookkeeper at the Bank of Michigan when the stock market crashed. From the time she was seven years old, there were nights she went to bed hungry, nights she read by candlelight because her parents couldn’t pay the electric bill. She knew the classes at Wayne were an extravagance. And besides, nice Jewish girls didn’t go off to New York alone, not when they could marry a boy like Ira. He picked her up from the university every Thursday and took her for an ice cream cone. Seeing him there, leaning against his pickup, waiting for her—it made her feel a sense of safety she had never known in her life. How could she give that up?

The house on Outer Drive became her canvas. She’d started smoking during the renovation and never quit. What fun she’d had putting her touch on each room once Ira made a name for himself in the barrel business and they finally had money to spare. Years later, she’d been ready to give up her marriage, but the house was another story.

“Nadine was too kind,” she told Sol now.

“Sometimes, I wonder if that’s what killed her,” Sol said. “She kept telling me she wasn’t feeling right, but I couldn’t get her to slow down. All her cooking for the girls and their kids, running over to their houses every other minute — caring for everyone but herself.”

Nadine had been the sort of woman who baked fresh challah and made an endless supply of kreplach and matzoh ball soup. Frances wasn’t that kind of bubbe. She worked on Shabbos and could barely make gefilte fish from a jar. She offered her family a different form of sustenance, her own irreverent wisdom. Just last week, she’d told Josie to take up smoking because it looked better than biting her nails. The girl laughed so hard, she forgot about the latest boy who’d stomped on her heart.

Still, when Fran’s time came, no one, surely not her family, would say she was too good for this world. She put her hand on Sol’s arm and escorted him to the long table at the back. “Sit down, Sol. I have a few ideas.”

There was no one else in the store, so she waved Josie over and told her to bring in the samples from the most upscale imprint she carried. Elegant, yet understated. Josie lugged two huge bound books from the office and dropped them onto the Formica surface.

“I’m taking my break,” she said. Without waiting for a response, she took that damned CD player from the shelf underneath the register, plugged in her headphones, and blocked out the world.

Sometimes, Josie showed real interest, sitting next to Frances when she went through the books and even making suggestions. “Gram, what about this one for the Keppler bar mitzvah? They want something modern.”

But lately, she seemed distant, distracted. Frances was used to dealing with the fickleness of a teenage girl’s moods. She’d suffered through raising two of them — Josie’s mother and aunt — with far less grace than Nadine Goldstein.

Sol must have read something on Frances’s face. “Let her be,” he said.

Frances usually bristled when people told her how to behave, but coming from Sol, it seemed like a gesture of compassion. And so she opened the book and began her spiel: the various options for style, color, paper, and calligraphy. Sol listened and nodded, gradually narrowing down his selections.

“This is terrific, Fran. I wouldn’t have known the first thing about all this.”

“Why don’t you bring Anna in next week and see what she thinks?”

“I’d love to. It’s just — ” He closed the book, placed his hands on the cover. “I can’t afford anything fancy. You know I sold the business last year? I didn’t get as much for it as I’d hoped. And Anna’s fiancé doesn’t come from money, so I’m paying for everything.”

“Don’t worry about that, Sol. I want to get you these invitations at cost.”

“But that means you wouldn’t make a dime! Oh, I can’t let you do that, Fran.”

“Sure, you can. You’re an old friend.” She tapped him gently on the shoulder and he flinched, as though he’d forgotten the feeling of another person’s touch. “Well, I’m old. That’s for sure.”

She laughed. They both did.

“Would you like to have dinner with me sometime?”

“I’d like that very much, Sol.”

“How ’bout tonight? I mean, carpe diem and all that, right?”

“Oh.” What was this, dinner with a friend or something more? Never could she have imagined going on a date with Nadine Goldstein’s husband. But what the hell? The woman had been sprouting weeds at Clover Lawn going on four years now.

She smoothed the ends of her leopard-print scarf. “Tonight sounds fine. I’d invite you to the Club, but you know, Ira kept our membership.”

Ira now mainly used the membership to showcase his armpiece, who was a dead ringer — at least in Frances’s mind — for Zsa Zsa Gabor. Three years into the relationship, Frances still wanted to vomit every time she thought of Ira watching the Hungarian take a putt in her little white skirt, or their hands entwined beneath linen napkins in the dining room. All the “who’s who” of the Jewish community belonged to the Club, but she could no longer afford the dues on her own.

“I never liked that place anyway,” Sol said, suggesting instead the Greek diner less than a five-minute drive from her condo. She ate there at least three nights a week, partially because she hated to cook, partially because the waitresses didn’t make a fuss when she sent back her plate, and partially because she was tired of staring at Poirot’s twirled mustache.

“Perfect. 8:00?”

His eyes widened. “I’m usually in bed by then.”

Of course, he was a fan of the early-bird special, like most people their age. Frances had always felt most awake at night. Sometimes, she drove over to Walgreens at 10:30 and browsed the magazine racks. Sometimes, she got so engrossed in an Agatha Christie that she stayed up until 3:00 in the morning. Josie used to call around midnight and Frances would let the girl prattle on about the boys who didn’t know she was alive, her problems with her mother. But in recent months, the calls had stopped. Frances dreaded the nights of endless silence.

“7:30’s my final offer, Sol,” she said.

“Done. See you there.”

He leaned over and kissed her on the cheek. What you might call “a peck,” reserved for the rebbetzin or an elderly aunt from the Old Country who didn’t bathe often enough. She couldn’t tell if he was out of practice or if this was his way of letting her know they were just having dinner, nothing more. In any case, she decided it wouldn’t hurt to tidy up.

________

Frances went home after work and put on a lime-green cardigan she’d purchased at Saks Fifth Avenue during her last trip to New York. She combed her hair, trying not to dwell on how thin it had become, and traced her lips with Revlon. She was going for a certain look: put-together but not too put-together.

He was waiting in a booth when she got to the diner. Meribeth, the cheerful waitress who put up with a lot of Fran’s nonsense, dashed over.

“Hi, dear. The usual?”

It annoyed Fran to be addressed as “dear,” as though she were a little old biddy who needed to be sweet-talked like a child.

It annoyed Fran to be addressed as “dear,” as though she were a little old biddy who needed to be sweet-talked like a child.

“Yes, but don’t forget to put the gravy on the side. And make sure my mushroom barley soup is hot this time. Nothing worse than lukewarm soup.”

“You got it.” Meribeth smiled sympathetically at Sol. If Ira had been here, he would have smiled back, a gesture of apology that drove Frances mad. What was the problem with liking things a certain way?

“I’ll have the same,” Sol said. “And I agree about the soup. Nothing worse.”

The conversation was easy. Meribeth brought over a plate of pita parm, a staple of the place. They both crunched on the cheesy bread.

Sol brushed crumbs off his shirt. “You’ve done such marvelous things with the store. Nadine used to say how much she admired you. Starting over, like you did.”

Frances told him how she’d sat on a therapist’s velvet settee nine years earlier. It was soon after the divorce and she thought she was losing it. The days that had once been filled with cooking and cleaning and caring for Ira and the girls were empty. The minutes and hours ticked away. Time stretched into nothingness. It wasn’t Ira she missed, but the rhythm of being married. She wasn’t sure she could survive this new, shapeless existence.

The shrink, who insisted on being called “Nancy” instead of “Doctor,” had short gray hair, pink lipstick perpetually smeared across her front teeth, and an odd collection of rain sticks. She ran a group called “Transitions” at the temple on Tuesday nights. Am I crazy, Nancy? Frances had asked.

“She said I needed to do something,” she told Sol now.

Frances had known it was too late to go back to her fashion illustrations. Hell, department stores didn’t even hire illustrators anymore. And these days, they preferred fourteen-year-old models who looked like they hadn’t eaten in weeks. The way the clothes hung on them, their bones poking out — she couldn’t understand how that made someone want to buy. The models she had painted weren’t exactly zaftig, but they had figures. And they were beautiful. Real women.

Even though she was no longer suited for that world, she still had her artistic flare. The idea of opening a store had come to her during a solo trip to Palm Beach. Nancy had sent her to a spa to “chill out,” a concept that Frances, a daughter of the Depression, thought frivolous and self-indulgent. But it was on that trip that she wandered into a little stationery and invitation store. She stood browsing the shelves, picking up the occasional birthday or anniversary card and examining its design. Behind the counter, a woman who looked to be about her age tended to customers coming in and out. Some told her about parties they were planning. They asked what she thought about this or that. The woman swanned around the compact space, pointing out different merchandise.

Her customers’ eyes followed her, and Frances’s did, too, as though the woman were a magnet drawing them in. She wore stylish glasses with little rhinestones in the corners and a simple black dress that made her look more New York than Palm Beach. Can I help you? she finally asked. I’m Dottie.

Yes, Frances thought. Maybe you can.

Before she could think better of it, she had asked Dottie if she could be her apprentice. She’d rent an apartment in Florida for the winter, work in the shop and learn the business.

“All those years, Ira handled our finances. I couldn’t even get my own credit card till I was forty-eight,” she told Sol. “I didn’t know the first thing about running a store.”

“And look at you now.” Sol beamed.

Frances was a little embarrassed by the praise. She had been talking too much and she needed a break. She set her lighter on the table.

“You’ll have to excuse me, Sol. It’s a dirty habit. I promised my daughters I’ll quit when I turn a hundred.”

“It doesn’t bother me. I’ll be right here.” He tapped the edge of the table twice. Right. Here.

_________

Sol called her at the store the next day. “I’m not one to play games,” he said, “so I’ll come right out and say it: that was the best night I’ve had in years.”

Frances cradled the cordless phone between her cheek and shoulder as she rang up a box of thank-you notes for Alma, who managed Blum’s Drugs next door. Debra Kranzen was waiting for her at the long table, eager to see samples of her son’s bar mitzvah invitation. Frances was busy and couldn’t quite match Sol’s enthusiasm, but it had been a nice night. She told him so.

“Let’s do it again next week?” he asked. “Same time, same place?”

And so it became a new part of her routine. Something in between her nights at the bridge club and her evenings spent at home, massaging her sore feet. Three Tuesdays in a row, they met at the diner. They reminisced about Central High School, caught up on which of their friends had rented condos in Boca or Naples for the winter, laughed about their adult children who were now dealing with teenagers of their own. “Payback,” Sol said. He wasn’t much of a reader, but he listened intently when Fran talked about the Churchill biography she’d checked out from the library. And she enjoyed seeing him come alive — his voice rising, arms pumping in the air — when he recapped the latest Tigers game, never losing faith in the team no matter how badly they lost.

She wasn’t sure they were an item, but they were something. She thought about this when she took her smoke break during their fourth dinner together. As she puffed away on the sidewalk bordering the parking lot, she decided they didn’t need to define it. It was a bright spot in her week, whatever it was.

When she returned, he got up from the table, walked to the front, and helped her take off her wool coat. He draped it over a plastic hanger swinging from the rack by the register. As they sat back down at their booth, Meribeth came over to collect their empty plates.

“Ready for your coffee? We have that apple pie you like, too.”

Frances yearned for her caffeine fix, but Sol reached across the table and grabbed her wrist. He looked up at the waitress. “Give us a few minutes,” he said.

He held her hand in his. “Fran, there’s something I wanted to talk to you about. Maybe we could go back to your place so we could have some privacy?”

She drew her hand away and considered this. Sol Goldstein, smooth operator. Who would have thought? But then, maybe he just wanted her advice on Anna’s wedding without half the Jews of Metro Detroit listening in. Or maybe he was having some problem with his finances or health, and needed an old friend to lean on. She could do that, if not for him, then for Nadine.

“Sure, Sol. Let’s get the check.”

“I’ve got it. Let’s just go.” He began to fidget. Before she could open her purse, he pulled two twenties from his wallet, stuck them under the napkin holder, and stood over her, breathing heavily, as if his life depended on their exiting the diner at that moment.

_______

Sol followed her back to her condo in his Buick. Inside, she flipped the light switch and led him into her living room. He eyed the picture frames on the bookshelves of her girls and their families. “I remember Maxine and Sharon when they were in diapers,” he said. “Time marches on, doesn’t it?”

“That’s the only guarantee in life. Want some coffee?”

“I don’t drink coffee so late, but some tea would be nice, if you’ve got herbal?”

She padded into the kitchen and put a kettle on the stove. He made himself comfortable on the couch, drawing her woolen blanket over his legs. She sat down at the other end, tossing a throw pillow onto the chair.

“If I’d known you were coming, I would’ve picked up some babka or something.”

“I don’t need any special treatment. I just like your company. You’re intelligent and dynamic and so damn funny.”

She felt her cheeks growing warm. She was surprised at the feeling.

“You know, Fran.” He inched closer to her end of the couch. “I really hate being alone. Don’t you?”

“Sometimes, yes. But I’ve gotten used to it.” Even with the store, her bridge club, and the handful of friends she still spoke to, the silences could be brutal. The long evenings inside her own head. If something were to happen — if, God forbid, she met the same fate as Nadine Goldstein — how long would it be before someone discovered her corpse?

“You shouldn’t have to get used to it.” He reached again for her wrist. “I think the two of us could make a nice arrangement.”

She stared at him, confused.

“I mean, the two of us … making a shidduch. For ourselves.”

He took her left hand and held up her ring finger. After forty years with Ira, it still felt strange, that naked finger. Sometimes, she could almost feel the edges of the Asscher-cut diamond he’d given her on their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, like a phantom limb. She had pretended to be happy with the gift, but in reality, the original ring, purchased when they were young and broke, had meant more than the fancy replacement. They couldn’t get enough of each other then, and it had symbolized the bright, sparkling future that lay ahead of them.

She was too weary to start down that path, with all of its empty promises, a second time. And with Sol? Sol Goldstein? She had never thought of him that way, and even after four “dates,” she still didn’t. And yet, she’d felt something, hadn’t she? Just moments before, when he paid her a compliment, a current had charged through her — as if her nerves were waking up from a long slumber.

She laughed nervously. “You’re kidding, right?”

He peered into her eyes, searching, she would later imagine, for some trace of humanity. His voice grew softer. “Why would I joke about something like this?”

“Sol, I like you. I respect you,” she said. “I don’t love you.”

“Oh, please.” Sol’s arms shot up in the air. “This has nothing to do with love. It’s about having someone to wake up with in the morning. Someone to care for you as you get older.”

She tried another tack. “The truth is, I was never good at marriage. I think I’m too difficult to live with someone else.”

“Come on, Fran, you were with Ira for forty years!”

“What I mean is, I’m impatient. I can’t talk to anyone before I’ve had at least three cups of coffee. I think most people are bastards — ”

“You don’t scare me, Fran. We can learn to love each other.” He reached over, squeezed her thigh, winked. “If you’ll show me where the bedroom is, we could start tonight.”

Frances rose, startled.

“Sol, I’m sorry, but I just can’t.”

He stood and put his face close to hers. He still had a bit of feta and parsley in his teeth. “You know what you are, Frances Abraham? A virgin grandmother!”

She chuckled. Did he really think she was some nun? A Jewish nun, at that. It wasn’t that she hadn’t let a man touch her since Ira. She had. The first was a setup, somebody from the temple’s brother-in-law. Or was it a cousin-in-law? He was handsome enough. She decided the moment she saw him waiting for her at the restaurant bar that she

would invite him home. She wanted to get it over with. She had never been with anyone besides Ira, and she didn’t even know if she was any good at it. She was surprised when it was all over, and the man looked at her incredulously, sweat lining his upper lip. “My God, Fran,” he said. “Pass me one of those cigarettes.”

There had been a handful of others since then, but none had meant anything. It was a revolutionary concept: You could make love without being in love. Still, she wasn’t really cut out for it, the intimacy that wasn’t intimate. And it felt wrong, false, to invite Sol into her bed, knowing she couldn’t pretend. Not with the ghost of Nadine Goldstein hovering above like Fruma Sarah.

Sol looked like a wounded animal hanging its head. She patted him on the knee. The tea kettle hissed.

“I should get home,” he said.

“Come on, Sol, don’t be like this.” Now, she was the one coaxing. They’d had a nice time. And they could have more evenings like this: dinner, maybe a movie afterward, talking about old times. Why ruin it?

“It’s okay, but we aren’t getting any younger.” He glanced at his watch. Nadine had the inside engraved, Time marches on, but I’m still crazy for you.

“I want you to be happy,” was all Frances could think to say. “I’m just not the one.”

He put on his coat without a word as she opened the front door. The air was crisp. It was an autumn night that would have been perfect for two old friends to curl up on the couch, warming themselves with a blanket and a mug of tea and good conversation.

As he headed down the front steps, she called after him, “See you next week?”

He touched the brim of his Tigers cap and looked away. “Goodbye, Fran.”

______

Sol reappeared in her store four months later. It was December, close to the holidays. He removed his cap and shook off the snow. He looked healthier somehow. His cheeks were fuller and his skin nearly glowed. There was a bounce in his step, a flicker of youth.

Ilustration by Laura Junger

“Happy Hanukkah, Fran,” he said.

“Sol, good to see you.” She came out from behind the register. Josie was working that day, but Frances had let her go in the back office to study for her math final.

“You, too.” He leaned against the counter, scanned her eyes before speaking. “I’m sorry I never came back here about Anna’s invitations. I guess I was … embarrassed. Nadine would have told me how childish I was. I even drove past the store once. I just couldn’t bring myself to come in.”

Frances figured he’d gone to one of her competitors for his daughter’s wedding. The thought had made her seethe. Now, she could almost feel sorry for him.

“That’s alright, Sol. We’ve known each other almost our entire lives. Like I said, I only want the best for you.”

“I know — and you were right about everything. I’m doing much better now. That’s what I came here to tell you.”

Fran sensed a tightening in her chest. She hoped he wouldn’t bring up the marriage business again. But then, part of her felt something else. Maybe she had been too hasty about brushing him off. She missed their dinners together. Would it be so bad to wake up next to him in the morning, to tell him which of her high-maintenance customers had given her an ulcer at the end of a difficult day?

He whispered into her ear, as though he were letting her in on a secret. “I just wanted you to hear it from me before you see us in the Engagements section of The Jewish News next week.”

Frances dropped the pen in her hand, forced a smile. “You found someone. I’m so glad.”

“It’s only been three months, but Veronika’s a real doll. We actually met at this thing Ira and Elena threw at the Club.”

Veronika. Probably another fucking Hungarian! Maybe she was a lookalike friend of Elena’s. Maybe there was an army of them: thousands of Zsa Zsa robots who swooped in and took every eligible man over fifty off the market.

Frances bent to pick up the pen, clearing her throat. “I’m thrilled for you, Sol. I really am.”

A look of relief crossed his face. “Oh, Fran, you don’t know how much that means. I’ll admit, I was a little nervous about coming here today.”

He had offered her the job first and she had turned it down. So, why did she feel something sour rising up from her stomach?

“Don’t be silly! Listen, let’s find the two of you some gorgeous invitations. I — I can get them for you at cost like I said I’d do for Anna.”

He waved his hands in front of his face. “I couldn’t ask you to do that.”

“Please, Sol, it’s no bother.”

“Not after, well, you know …”

“I insist.” She clutched the pen to her ribs. “I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Sol sighed deeply. “You’re something else, Frances Abraham! Okay. Of course, Veronika knows all about your store. She’ll be over the moon.”

“Good.” She grabbed her legal pad and flipped through the pages. “Why don’t we look through some books and then narrow it down, like we did before?”

The room was starting to spin. She gripped the counter.

“Gram?” Josie stood in the doorway of the office.

“Would you excuse me a minute, Sol?” She pulled out a chair for him at the table, then followed her granddaughter into the back room.

Josie closed her precalculus textbook with a dramatic flick of the wrist. “I’m done studying this boring shit,” she said. “I can help now.”

“No, it’s alright,” Frances said. “I’ve got this one.” She got down on her knees, searching through a stack of sample books on the floor. For a moment, she imagined herself the bride. What if she’d said yes? She would choose the finest paper, the most elegant script. But then she thought of coming down the aisle in a white dress, the fabric itching, her Hadassah arms jiggling. The whole thing seemed ridiculous — to put on a show as though they were kids. You don’t get do-overs in life.

There was a ringing in her ears. She lay down on the floor and stared up at the ceiling.

Josie stood over her. “Are you sick, Gram?”

“Just a little dizzy is all. I didn’t eat breakfast.”

Josie knelt down, helped her to her feet. “Have my bagel.” She pointed to the desk. “I’ll take care of that guy.”

Josie took the bound books and Frances didn’t stop her. She sat down at her desk, unwrapped the sesame bagel from the wax paper, took a bite, then another. Cream cheese fell onto her lap, but she didn’t care.

“My grandmother had to take a call,” she heard Josie tell him. “But I’m happy to show you what we have.”

Frances kept quiet, let herself be cared for. She lit a cigarette and took her time with it.

She’d had a little bell installed above the front door. When she heard it chime, she knew Sol was gone. Josie came back, a grin spread over her face. Frances was always telling the girl not to slouch, and now she stood tall, as though she had finally grown into herself.

“He really liked what I showed him. He said I’ve got great taste, like my grandma.”

Frances tried to get up from her chair. She was proud, really proud, yet she also felt weighted to the seat. “You’re a natural, Joseleh,” she said weakly.

Josie put her hand on Frances’s shoulder. How badly she needed to be touched right then. Thing was, Sol was right. She did hate being alone. Sometimes, in front of the mirror, she’d catch herself brushing her palms over her bare arms — feeling Ira’s strong hands, their heat. Look at us, he used to tell her. She heard it from practically everyone: How could you let a man like Ira get away? And now it would be: How could you refuse a mensch like Sol? And at your age? How many chances have you got left?

Her life had been one misstep after another, from the time her art professor had offered to help her get a scholarship to Pratt — and she’d told him, the words rolling easily off her tongue, Don’t bother.

“Did you get your heart broken, Gram?” Josie asked.

Frances balled up the wax paper and tossed it in the trash bin.

“I’m too old for that.” It was too late for her to reverse course, but maybe she could help her granddaughter avoid the same mistakes. At last, she found the strength to stand. “Let me show you something.”

Against the back wall, there was a cardboard box. She’d kept it sealed for years, but now she took a boxcutter and sliced through the packing tape. Then she peered inside, relieved to find the contents intact. Her illustrations had lasted, a time capsule of a life she’d never had. She stared at her drawing of a woman wearing a green tweed coat with a thick fur collar. She remembered the model, the way she’d stroked the soft mink around her neck. Frances took another from the pile. This one wore a long silk evening gown, a white-gloved arm propped on her hip. She handed Josie the illustration.

“Is that … you?”

Frances laughed. “Are you kidding me? We could barely afford milk and butter, let alone a dress like that.” She pointed to her signature: Frances Perlman, 1940.

Josie stared at the drawing. “This is really good, Gram. So, you were, like, an artist?”

“I wanted to be. A long time ago, when I wasn’t much older than you.”

“What happened?”

It was an innocent question from a girl who had never known what it was to be hungry, so hungry that the emptiness within her was not just a pit but a chasm. Frances had been first in her class, but as far as her parents were concerned, continuing her education was a waste of money they didn’t have. And why did she need more schooling? All roads led to the same destination anyway.

“Life,” she said.

She put the illustration back in the box. At some point, she had thought of framing a few and hanging them around the store. But each time she went through the stack, all she could see were flaws: a woman’s eyes too big for her face, an errant paint smudge in the background, her renderings of the fabric looking flat and stiff. She was only a beginner, after all, when she took the class at Wayne. She had promise, but no training. In any case, she decided she didn’t want a daily reminder of who she could have been. She’d shoved the box underneath some paper samples and botched orders.

What had made her dig them up now? She was foolish to think Josie could understand the importance of some mediocre drawings.

“What I’m trying to tell you is — ” She wanted to grab Josie by the shoulders and warn her. The dangers of marrying too young, of putting your dreams in a box. Years ago, Frances had asked her daughter why she and her girlfriends were marching around with signs all over the University of Michigan campus. Because we don’t want to end up like you, Sharon had said. Frances didn’t understand it at the time, why her life was so unappealing. She’d raised two humans, hadn’t she? She’d made and kept a home.

Then, all of a sudden, she was sixty and single. The very thing she had feared when she decided she would rather give up Pratt than bear the ache of lonely nights. She hadn’t known herself well enough. Her solitude was bashert, she now realized — whether she had gotten on that train to New York or not. Always get on the train, was what she wanted Josie to know.

She faced her granddaughter. Josie towered over her in her platform boots. “My art teacher, he believed in me. When someone sees something in you, promise me you’ll listen?”

“Yeah, sure, Gram.”

Frances thought that was the end of it. As usual, her words had gone in one ear, out the other. But then Josie leaned against the wall, surveyed the room. She folded her arms across her chest, and Frances saw a glimpse of the woman she would be.

“I think that teacher, if he could see you now, he’d be proud.”

Frances glanced around. At the bound books and boxes. The fax machine on her desk. The monogrammed notepad with her milelong list of to-dos. She felt a softening, an affection so deep, she could hardly contain it.

Here she was, in her red blazer, in her own damn store.

Maybe this was bashert, too.

The bell chimed again. Frances took out her compact and reapplied her Revlon. She stared at herself before putting the mirror away. For a moment, the room stopped swaying and the floor felt firm beneath her.

Her granddaughter was ahead of her, rushing out to greet the next customer.

Kate Schmier was born and raised in Metro Detroit and lives in New York, where she is working on a novel.