Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

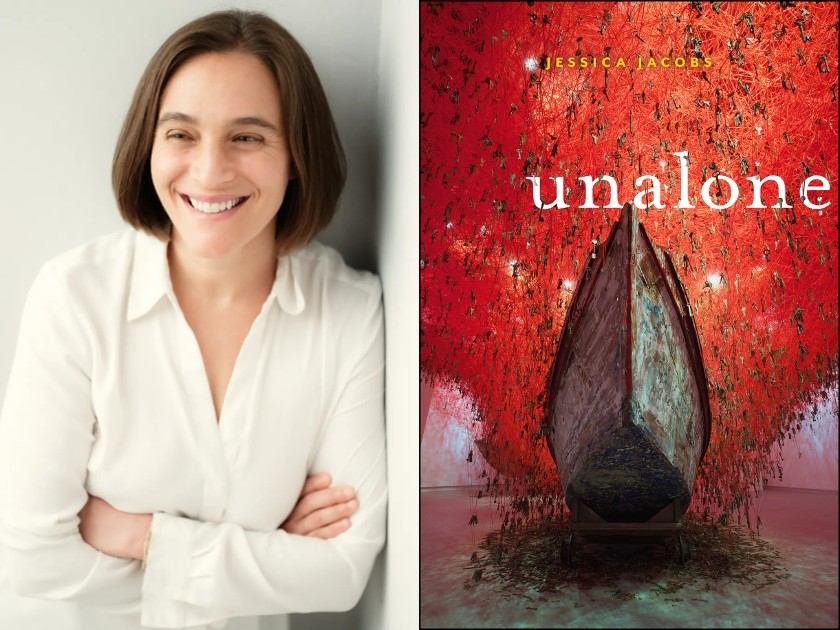

Author photo by Parker J Pfister

Jessica Jacobs’s third poetry collection, unalone, mines Genesis to create an extraordinary poetry collection informed by the Torah and in conversation with contemporary life.

In this interview, Jacobs discusses how she made these poems, being childfree, writing with the ancestors, and founding Yetzirah, a community for Jewish poets.

Julie R. Enszer: Congratulations on this new book! Can you talk a bit about how the idea of this book began? How did it take shape to build a collection of poems around the stories in Genesis?

Jessica Jacobs: Thank you, Julie; so lovely to be in conversation with you. I wrote nearly all of my first book, Pelvis with Distance, in a primitive cabin in New Mexico. That month alone in the high desert, without internet or phone, allowed some existential questions to emerge and take hold. As a result, literature — my go-to resource for wisdom — seemed a little thin. So in my mid-thirties, I read the Torah in its entirety for the first time. And because I can’t really understand something without writing about it, I found myself writing poems in response to what I was reading, amazed by how this ancient text spoke so directly to my life and the larger world.

JRE: The poems of unalone demonstrate both a deep study of the Torah and contemporary engagements with its stories. As I have been reflecting on the collection, I’ve been puzzling about the temporality of the book. It is rooted in gestures that look to the past, to the stories in Genesis, and yet is committed to examining the present. How did you think about that balance in assembling the collection?

JJ: I wrote this book parshah by parshah, taking a deep dive into each along with related midrash and commentary, and contemporary scholarship by brilliant thinkers like Avivah Zornberg and the Rabbi Jonathan Sacks (z”l), often racking up sixty or seventy pages of notes per portion. As I went, I interspersed those recorded lines with my own questions and memories that rose up to meet the text, grateful again and again for the companionship I found in these stories and how they led me in surprising directions, forcing me to look at issues like the climate crisis, systemic racism, and antisemitism, as well as the darker parts of my own psyche. So in a way, I think of these as poems rooted in deep-time, simultaneously reaching toward the past, which serves as both a clarifying lens for the present, and as a spur to imagine what might come next.

JRE: The poems in the collection seem to be a mixture of midrash and lyric poetry. Did you think of those as two different gestures as you were writing these poems — midrash and lyrics? Or are the two indelibly intertwined for you?

JJ: Because writing unalone was its own kind of study, and I believe it’s far more powerful to come to the page — and to life, really — with not answers but questions, I tried to let each poem tell me what it wanted to be. While I naturally focus on sound and lyricism as important tools in the transmission of meaning, Torah and midrash was the rich humus from which they grew and so these poems inevitably carried those teachings within them.

JRE: unalone demonstrates new and interesting innovations in your work. What is your writing process? How do your poems find their form?

JJ: When I use forms, whether a received form like the sonnet, or one more self-invented, it’s with the intent to communicate something that might perhaps be a bit extrasensory. For example, Torah repeats the tale of a woman who was barren until God, that divine obstetrician, intervenes and allows her to get pregnant. As someone who’s made a choice to remain childfree, though it’s a choice with which I’ve wrestled, and as many of my friends who wanted children struggled to have them, I bristled at the idea often expressed in these stories that the only way to truly be a woman with a complete life was to be a mother. So in “Sing, O Barren One, Who Did Not Bear a Child,” the ghazal, where the final word of each couplet repeats, felt like the perfect vehicle for this repetition and rumination.

For poems like “That We may Live and Not Die: A Deep-Time Report on Climate Refugees,” which identifies Joseph’s family, in their move from Canaan to Egypt during a famine, as the first climate refugees on record, it seemed only natural to borrow its form from a report by The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

As for the shift in my work, I truly believe that we write as we live. Pelvis with Distance was not only written in the austerity of the desert but in a time when I was still nervously finding my feet as a writer; so the poems are more austere, more controlled. Take Me with You, Wherever You’re Going was written in the love and rush of the first years of my previous marriage; so the poems there are more expansive, more likely to range across the page. In the seven years I spent researching and writing unalone, I felt like the only way to truly engage with this material was to give myself over to mystery. Which is to say I had to be more of a conduit than a controller, and to allow the poems and teachings to move through me in the ways they most needed.

JRE: The final poem in the collection “Aliyah” engages the images of the Torah and trees concluding with the line, “All of us, in that overstory, unalone.” Can you talk a bit about the title, how you selected it, and what it means to you?

JJ: When I first learned that the Torah was also known as the Tree of Life, one which through study we could plant within ourselves, I fell in love with this metaphor. So when my wise friend the poet Matthew Olzmann suggested I might want to add one more poem to my book reflecting on why I’d felt compelled to write it and what this work had meant to me, I wrote a nearly complete draft of “Aliyah” in a single sitting (and, as whatever the Jewish equivalent of an Easter egg is, the poem happens to be eighteen lines, the numeric equivalent of chai, life). It was a beautiful opportunity to explore the community into which this work has granted me entry, the connections it’s allowed me to feel with others, and, as a gift, in the poem’s very final word, the book’s title made itself known!

JRE: Throughout unalone, there are many maps of your poetic and intellectual influences; there are not only parashot from the Torah but also quotations from Viktor E. Frankl, Audre Lorde, Jean Valentine, Wendell Berry, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, and more. I hope readers trace the references that you make. What books and poems do you return to regularly?

JJ: For each book, I’ve found the poetry equivalent of a soundtrack, of collections I read to help guide me as I go and set the mood for this particular writing. Ellen Bass’ Indigo taught me how to search for the spirit while staying grounded in the body. Marie Howe’s oeuvre is a masterclass in letting the messy world into a poem that asks big questions. Yehoshua November’s Two Worlds Exist showed me how Jewish teachings might illuminate and inspire. Rilke’s The Book of Hours was the lyric companion for my series “And God Speaks.” And pretty much all of both Alicia Ostriker’s and Eleanor Wilner’s poetry and prose feel like both oracles and wells, sources to which I am constantly returning.

While I naturally focus on sound and lyricism as important tools in the transmission of meaning, Torah and midrash was the rich humus from which they grew and so these poems inevitably carried those teachings within them.

JRE: And given that each parshah is associated with a week in the Jewish year and that Genesis covers only a part of the year, will there be more collections that consider the other books of the Torah?

JJ: Fortunately for me, Exodus through Deuteronomy are all in conversation with each other, which I think means my next book will be able to cover more biblical ground. As I’m now in my forties, newly untethered from marriage, I’m very interested in the journey through the wilderness as a way to explore the concept of our movement into and through middle age. And, don’t tell my poems, but I suspect this next book might well be prose …

JRE: The founding of Yetzirah, a nonprofit literary organization dedicated to supporting Jewish poets and Jewish poetry, provides a context for this book and the work that you are doing in it. Can you talk a bit about Yetzirah and your path to founding it? How do unalone and Yetzirah connect?

JJ: When I first began this study, I was surprised by how difficult it was to find other Jewish poets and their work from which to learn and be in conversation.

At the same time, there were terrifying antisemitic attacks occurring throughout the country, including the white supremacist Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville and the shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. This made it feel all the more urgent for Jewish poets to have a safe and supported space, a place of real community within the literary world – which has proved doubly true since October 7. Yetzirah welcomes and supports Jewish poets at all levels of their writing careers, which includes Jewish poets of all denominations, degrees of religious engagement, political beliefs, and identities, and welcomes allies of all traditions to join us at our events.

As poets, we write in chorus and companionship with our ancestors and contemporaries. And as Jewish poets, whether we write directly into and from our religion, culture, and history or not, we are part of an ancient tradition, one I want to explore with writers I admire. Toni Morrison said, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” Yetzirah is a community to which I wanted to belong; but it didn’t exist yet, so with the efforts and encouragement of our hardworking board and many around the US and abroad we are creating it.

JRE: What are you reading now and what are you looking forward to reading next?

JJ: I’m just finishing In This Place Together: A Palestinian’s Journey to CollectiveLiberation, written by Penina Eilberg-Schwartz with Sulaiman Khatib. Khatib is the cofounder of Combatants for Peace, a binational, grassroots nonviolence movement in Israel and Palestine, and this book feels like a vital window into the Palestinian experience, as well as the possibilities of joint nonviolence and the full recognition of everyone’s shared humanity as a better way, and really the only way, to move forward. As for my towering to-be-read pile, I fear it might one day topple and I’ll be found trapped beneath it. For new poetry, I’m excited to dive into Andrea Cohen’s The Sorrow Apartments and to spend more time with Philip Metres’ Fugitive/Refuge, with which through a wonderful twist of fate my book shares a cover image. And from my dear friend and chavruta Rabbi Burton Visotzky, to whom unalone is dedicated, I have The Road to Redemption: Lessons from Exodus on Leadership and Community to accompany me into the rest of the Pentateuch.

Julie R. Enszer is the author of four poetry collections, including Avowed, and the editor of OutWrite: The Speeches that Shaped LGBTQ Literary Culture, Fire-Rimmed Eden: Selected Poems by Lynn Lonidier, The Complete Works of Pat Parker, and Sister Love: The Letters of Audre Lorde and Pat Parker 1974 – 1989. Enszer edits and publishes Sinister Wisdom, a multicultural lesbian literary and art journal. You can read more of her work at www.JulieREnszer.com.