Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Author Ilan Stavans has three new books out this year, and will be introducing each one to Jewish Book Council readers as part of the Visiting Scribe series here on The ProsenPeople.

I am not being facetious: perhaps the first piece ever written from a Jewish perspective in what we call today Latin America are Columbus’s diaries. I don’t want to jump into the debate on his Jewish ancestry; still, his approach at describing the landscape, his utopian vision of the inhabitants of the newly discovered lands as he looked for a new route to the Indies, distill a Jewish sensibility. At any rate, less debatable are the scores of crypto-Jewish poems, essays, memoirs, and inquisitorial testimonies written in Peru, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, Cuba, and other places during the colonial period.

This has been an area of passionate research for me. I am in the midst of completing a travel book through the region, due out from Norton next year. In it there is a distinct way of looking at things, what the Germans call a weltanschauung. I know about it because I was born in Mexico. But I didn’t become a Latin American until I left home, to live first in the Middle East, then in Europe, and eventually in the United States. Becoming part of the whole redefined me.

The Jewish component of Latin America, both visible and invisible, is enormous. Of an overall population of 450 million, less than half a million identifies itself as Jewish, a minuscule number. Still, the impact on thought, commerce, politics, culture, and religion is significant. In the United States there are another 60 million people whose roots are traced back to the Hispanic world. Last year I saw a statistic, unreliable in my eyes, arguing that 200,000 of them are Jewish. The cipher must be considerably smaller. Still, the suggestion is tangible proof that Jewish-Latin American influence north of the Rio Grande is growing substantially.

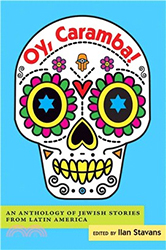

At any rate, I hope a place to appreciate such influence is Oy, Caramba! An Anthology of Jewish Stories from Latin America. The focus is literature, specifically the modern period, from the early twentieth century to the present. Yet literature is life. In other words, no aspect of Jewish life in Latin America is alien to these tales. Just as in its English‑, Portuguese‑, Yiddish‑, and Hebrew-language counterparts, there are tangible genealogical lines in Jewish-Latin American letters: a grandparent figure, a parent, and so on. The founder is Alberto Gerhunoff from Argentina, author of The Jewish Gauchos of the Pampas. His work, in part, is about immigrant, just like that of Abraham Cahan. Moacyr Scliar from Brazil, author of The Centaur in the Garden, is a delicious humorist, a kind of Sholem Aleichem. Isaac Goldemberg from Peru, published The Fragmented Life of Don Jacobo Lerner, about ethnic and theological mixing, what is known as mestizaje. Clarise Lispector, also from Brazil, is an astonishing stylist better than Virginia Woolf. Other authors are equally memorable: Marcos Aguinis, Angelina Muniz-Huberman, Eduardo Halfon, Marcelo Birmajer, Rosa Nissán, and Ariel Dorfman, among them. And I am only talking of those largely devoted to fiction.

There are Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Mizrahi authors, as well as descendants of crypto-Jews. Plus, there are myriad non-Jewish writers in Latin America with a lasting interest in Jewish themes. Carlos Fuentes, for example, wrote novels about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, José Emilio Pacheco about the Nazis in Mexico, Mario Vargas Llosa about Jewish-indigenous relations, and Leonardo Padura about the Holy Office. A puzzling chapter in Roberto Bolaño’s The Savage Detectivestakes place in Tel-Aviv. Nazism is a ubiquitous topic. There is Jorge Volpi’s In Search of Klingson and also Bolaño’s Nazi Literature in the Americas, an encyclopedia of nonexistent books on the topics.

Editing Oy, Caramba! was a joy. It includes stories originally written in Yiddish, Spanish, Portuguese, and English. (The volume is an expansion of Tropical Synagogues [Holmes and Meier], which appeared in 1994. This was the first anthology I ever published in English.) When I look at its contents, I wished it could have been at least twice the size. This is unavoidable. Anthologies, as everyone knows, are made of hors d’oeuvre: one of their objectives is to whet one’s appetite. But when they do their job well, they accomplish much more: they offer context, allowing readers to see beyond the surface; and they build bridges across authors, countries, and periods. Think of all the anthologies whose influence is decisive, from the Bible to The Arabian Nights. Mine is comparatively modest: to show that Columbus’s sensibility, complex as it is, lives on.

Editing Oy, Caramba! was a joy. It includes stories originally written in Yiddish, Spanish, Portuguese, and English. (The volume is an expansion of Tropical Synagogues [Holmes and Meier], which appeared in 1994. This was the first anthology I ever published in English.) When I look at its contents, I wished it could have been at least twice the size. This is unavoidable. Anthologies, as everyone knows, are made of hors d’oeuvre: one of their objectives is to whet one’s appetite. But when they do their job well, they accomplish much more: they offer context, allowing readers to see beyond the surface; and they build bridges across authors, countries, and periods. Think of all the anthologies whose influence is decisive, from the Bible to The Arabian Nights. Mine is comparatively modest: to show that Columbus’s sensibility, complex as it is, lives on.

Ilan Stavans is a Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College and the author of many books of both Jewish and nonsectarian interests.

Related Content:

Ilan Stavans is the internationally known, New York Times bestselling Jewish Mexican scholar, cultural critic, essayist, translator, and Amherst College professor whose work, translated into twenty languages, has been adapted into film, theater, TV, radio, and children’s books.