Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

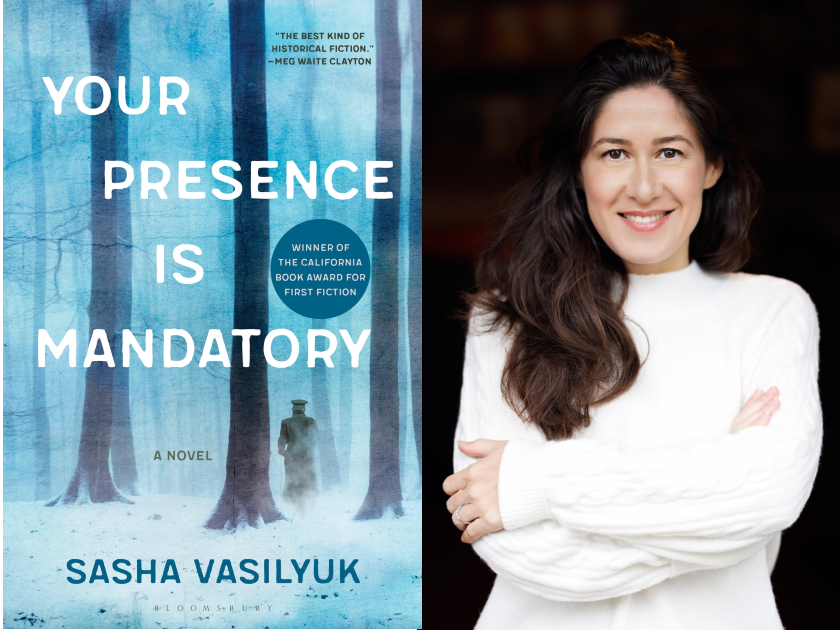

Author photo by Christopher Michel

Published last year to critical acclaim, Sasha Vailyuk’s Your Presence Is Mandatory has just come out in paperback with a gorgeous, haunting cover. Alina Adams spoke with Vasilyuk about the family history behind her novel, writing about Soviet Jewish experiences, and the responses she’s received about the book.

Alina Adams: After years of writing non fiction, what made you pivot to fiction?

Sasha Vasilyuk: I’ve always wanted to write fiction. For years, I was just afraid to. So in a way, nonfiction was the pivot and fiction was the correction back to the original course.

AA: Why did you think now was the right time for Your Presence is Mandatory?

SV: I started writing the novel in 2017 when I moved to Berlin. This was after I’d visited the war-torn Donbas region where WWII history was being used as propaganda. The links between WWII and what was happening in Ukraine in the late 2010s, as personified by my family, seemed novelesque. I worked on the book for the next four years and happened to finish it in February 2022, about a week before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Scarily perfect timing. In a way, I wish Your Presence Is Mandatory was less relevant.

AA: I know that the inspiration for the book came from family history, but how much did you have to research?

SV: A lot! I had very scant information to go on in terms of family history, especially about my Jewish grandfather who was the inspiration behind the main protagonist. All he left behind was a one and a half ‑page confession letter to the KGB, which was the seed of my novel. So while the skeleton of the book is based on real facts, I had to spend a lot of time researching to fill in the “meat” of the story.

AA: Did you ever, like me, come upon a situation where family history didn’t match the existing historical record? How did you rectify that?

SV: I’ve actually come across the opposite issue: where some Soviet-born people think that certain small things “couldn’t have been possible.” Except they were! I think that speaks to the presumed uniformity of the Soviet experience – we think what happened to us must have been the same as everyone else – but life in that vast empire actually wasn’t as uniform as we often think. So I’ve learned to trust the documents and the witnesses of the actual events over people who think they know.

Western readers, especially Jewish ones, tend to feel that this novel completes a missing piece of the puzzle. So many know about what happened to their relatives during the Shoah, but little to nothing about those who stayed behind the Iron Curtain.

AA: What sort of responses did you get to the story from Soviet immigrants versus American and other readers?

SV: Western readers, especially Jewish ones, tend to feel that this novel completes a missing piece of the puzzle. So many know about what happened to their relatives during the Shoah, but little to nothing about those who stayed behind the Iron Curtain.

The Soviet immigrant readers, on the other hand, are sometimes resistant to reading it – “because we already know everything.” But once they do, they are tremendously touched that this story— which is so similar to their story— has been put into a book and published across several countries. Now they want their kids and grandkids to read it!

AA: Elizabeth Gilbert pulled the publication of her Soviet-set historical fiction because she didn’t want it to come off as “pro-Russian.” Was that ever an issue for you in light of the Ukraine invasion?

SV: Yes, I wrote an op-ed for The New York Times about talking to my son about the war while continuing to teach him Russian (my native language). While many in Ukraine speak Russian – even today, even in public – my piece and, by proximity, my novel angered some Ukrainians on the internet. Luckily, those Ukrainians who’ve actually read the book, tend to be very touched by it.

AA: Why do you think we’ve seen such an increase in recent years of books from Soviet born Jewish authors?

SV: Because we’ve got things to say! Or maybe, because we finally learned English! But seriously, there are a couple million of us, so after a few writers paved the way (Gary Shteyngart, Lara Vapnyar, Irina Reyn, you), the slightly younger generation was bound to give it a go. The Soviet Union was one of the most radical experiments in human history and so much of it has been hidden or silenced that I think it lends itself well to storytelling. And then there is the immigration experience and the complicated Jewish identity to explore. So much material at our fingertips!

AA: Are there topics you think Soviet Jewish writers aren’t covering that they should? Why do you think that is?

SV: I think at first, a lot of Soviet Jewish writers focused more on the immigration experience rather than on stories set in the countries of the former Soviet Union. That meant that readers who search for “novels set in Russia” or “novels set in Ukraine” inevitably come across books like A Gentleman in Moscow and other novels written by American authors who have never slept in a communal apartment or cooked a single pot of borsch. In the past few years, that has started to change and I’m glad.

AA: What’s next for you?

SV: After a mostly (though not completely) historical novel, I’m turning my pen (or rather, keyboard) to the contemporary world, where a young Soviet Jewish immigrant finds herself ensnared in the Kremlin’s political games in order to help her father. It is my attempt to figure out how our personal, ethnic, and national identities intersect. Wish me luck untangling it all!

Alina Adams is the NYT bestselling author of soap opera tie-ins, figure skating mysteries and romance novels. Her Regency romance, The Fictitious Marquis was named a first Jewish #OwnVoices Historical by The Romance Writers of America. Her Soviet-set historical fiction includes The Nesting Dolls, My Mother’s Secret: A Novel of the Jewish Autonomous Region, and the May 2025 Go On Pretending. More at: www.AlinaAdams.com.