Matthew Baigell is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Art History at Rutgers University. He is the author of numerous books, including American Artists, Jewish Images, and Jewish Art in America: An Introduction. His most recent book is Social Concern and Left Politics in Jewish America Art, 1880 – 1940. He will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council’s Visiting Scribe series.

Before anything else, I want to say that I never use the phrase “Jewish artist” but rather artists who are Jewish, because placing the word “Jewish” before “artist” implies that an artist’s entire identity is tied up with being Jewish. It is the same thing as saying “an obese person” rather than “a person who is obese.” And I also believe that there is no such thing as Jewish art, but rather art with Jewish content. Unless somebody can find the biological and cultural roots connecting centuries’ of divergent Jewish cultures (Ashkenazic, Sephardic, North African, Middle Eastern, Indian) as well as between male and female, rich and poor, religious and non-religious, and rural and urban artists who were/are Jews. Most people think of “Jewish art” as something by artists like Marc Chagall, but he and others like him came from a particular area (Eastern Europe) at a particular time in history (late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries).

Before anything else, I want to say that I never use the phrase “Jewish artist” but rather artists who are Jewish, because placing the word “Jewish” before “artist” implies that an artist’s entire identity is tied up with being Jewish. It is the same thing as saying “an obese person” rather than “a person who is obese.” And I also believe that there is no such thing as Jewish art, but rather art with Jewish content. Unless somebody can find the biological and cultural roots connecting centuries’ of divergent Jewish cultures (Ashkenazic, Sephardic, North African, Middle Eastern, Indian) as well as between male and female, rich and poor, religious and non-religious, and rural and urban artists who were/are Jews. Most people think of “Jewish art” as something by artists like Marc Chagall, but he and others like him came from a particular area (Eastern Europe) at a particular time in history (late nineteenth- and early twentieth-centuries).

Having said that, I was always interested in Jewish-themed art based on ancient and modern texts (Torah, Talmud, kabbalah, daily and high holiday prayer books). My interest took a very serious turn when invited in the early 1990s to write an essay for an exhibition, “Painting a Place in America: Jewish Artists in New York, 1900 – 1945,” for New York’s Jewish Museum. I realized that although many were known as mainstream American artists, the importance of their Jewish backgrounds had been neglected. Most came from Eastern Europe where their religious and cultural heritage as well as their sense of community responsibility played a significant role in their Jewish identity. What was the impact of that identity on their art? Here was an area sorely in need of further research. And since the 1990s, exploring the relevance of that background has been the driving force of my work.

Most recently, I wrote Social Concern and Left Politics in Jewish American Art, 1880 – 1940, to make two key points. First, many, if not all, artists who were Jewish turned to political themes not because they were innocents seduced by figures such as Marx or Lenin, but because their Jewish heritage, prompted by notions of taking care of the poor, the needy, the hungry, and so on, blended well with left-wing ideals of providing those in need with better living and working conditions. For these artists, as had been articulated by many historians and sociologists, socialism was a secular form of Judaism. At the grassroots level today, there must be hundreds of American synagogues supporting programs that provide food, clothing, and financial support for those in need. The idea is the same even if the politics have changed.

The second point of the book was to show that the political concerns of the artists did not emerge during the Depression or the growing Communist presence in America during the 1930s, but had appeared as early as the 1880s at the start of the Great Migration of Jews from Eastern Europe. Concern and agitation for raising standards of living existed decades before the 1930s.

Two examples, the first from 1912 and the other from 1935 will illustrate these points. The earlier one, a cartoon, published in the December 12, 1912 issue of The Groyser Kundes (The Big Stick), shows how a political statement was presented within a Jewish cultural framework of social responsibility and human betterment. A tailor lights a menorah, each candle stem labeled with a political activity. The caption at the top is the beginning of the prayer said on Hanukkah on each of the eight days when candles are lit. “These are the candles that we light.” The tailor, his tape measure around his neck and the words for “tailor” written on his shoulder, holds the candle that lights all of the others. On it, the cartoonist, wrote “Enlightened.” Reading from right to left, the following words appear on each candle holder: “agitation,” “organization,” “strong union,” “ general strike,” “higher wages,” “shorter works hours,” and “better life.” The caption at the bottom states: “When the tailor lights the menorah, then all will be illuminated. Then there will be more joy and happiness in New York.”

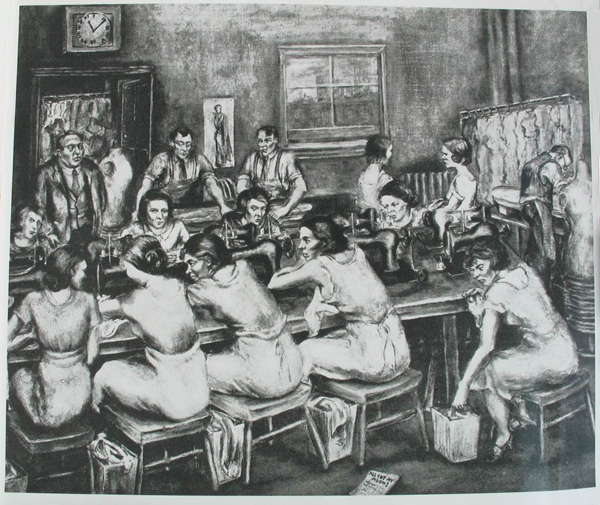

The second work, a painting by Selma Freeman, titled “Strike Talk,” painted twenty-odd years later, shows women garment workers taking control of their future by calling for a strike as a means to improve degrading sweatshop conditions. The piece of paper in the foreground states: “All out by noon,” indicates the nature of the conversation among the women. The men in the background seem clueless.

It is works such as these that are an important part of American and Jewish-American cultural history as well as American and Jewish-American art history and need to be remembered for what they tell us of the Jewish concern for social betterment.

Check back later this week for more posts for Matthew Baigell.

Related Content:

- How I Came to Write Jewish Artists and the Bible in 20th-Century America by Samantha Baskind

- Reading List: Jewish Artists

- Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Antisemitism, Assimilation, Affirmation edited by Rose-Carol Washton Long, Matthew Baigell and Milly Heyd

Matthew Baigell is professor emeritus in the department of art history at Rutgers University. He is the author, editor, and coeditor of over twenty books on American and Jewish American art. His most recent book is The Implacable Urge to Defame: Cartoon Jews in the American Press, 1877 – 1935.