One and a half million children died during the Holocaust. Many of those who survived did so in hiding: underground and in cities with fake papers; in haylofts and in sewers; in religious institutions and in foster families. Although they evaded the Final Solution, struggle and heartbreak defined their wartime experiences. Eighty percent of children who survived the war were orphaned. All of them spent formative childhood years in some form of hiding, often separated from their parents and moving between hiding spots and surrogate families, and most of them struggled with feelings of abandonment and dislocation postwar. These children were the lucky ones, but their lives, during the war and after, were anything but easy.

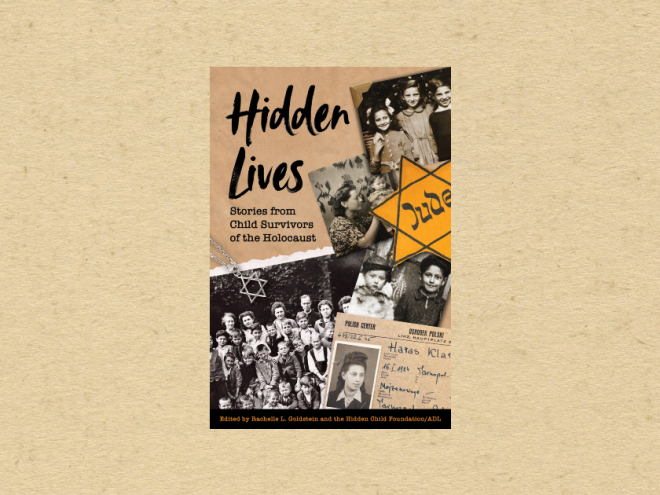

Hidden Lives, edited by Rachelle L. Goldstein and the Hidden Child Foundation (an affiliate of the Anti-Defamation League) tells the stories of some of these youngest survivors of the Holocaust. Most chapters are excerpted from stories originally published in the Hidden Child Foundation’s yearly newsletter. Although the excerpts may not be original, the compilation of stories covering such a broad range of wartimes ages, situations, and locations powerfully conveys both the diverse experiences of hidden children as well as the similarities that bind such survivors together. The book is divided into ten chapters, each of which covers a common experience of hidden children, from the initial separation from their parents to the special experiences of toddlers and infants to their mixed feelings upon liberation and reunion with surviving relatives. It is a credit to the volume’s editor that the stories never blur together; each feels unique and is told in the distinct voice of its author.

Common themes cut across the survivors’ recollections, regardless of where or how old they were during the war. Many recalled feeling unwanted, out-of-place, or burdensome while in hiding, which left them with lifelong emotional wounds. Many struggled with their identities, especially if they lived as Christians while in hiding. While most eventually returned to some form of Judaism, their postwar religious trajectories were not straightforward. A minority remained Christian, and some who had spent their tender years steeped in Catholic antisemitism struggled to accept their Jewish heritage. Likewise, reunions with surviving family members after liberation were often marked by angst and sometimes despair; some children did not want to leave their happy foster families, while others returned to flawed parents who had been emotionally destroyed by their time in the camps and ghettos. Most of the authors eventually emigrated to Israel or North America and achieved remarkable degrees of educational and professional success. Despite the challenges of a childhood spent in hiding, many of which persisted into adulthood, the young survivors proved resilient.

At the end of each entry is a brief biography of the author; many had passed away by the time of the book’s printing. The youngest survivors have now become the last survivors. Hidden Lives is a moving, well-executed, and important compilation of their stories that will only become more valuable to scholars and lay people as time progresses.

Meghan Riley earned a PhD in Modern European History from Indiana University. She is a postdoctoral fellow at Northern Arizona University.