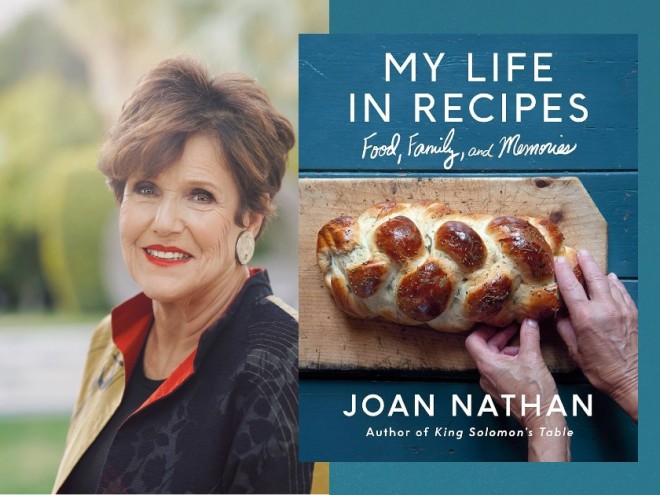

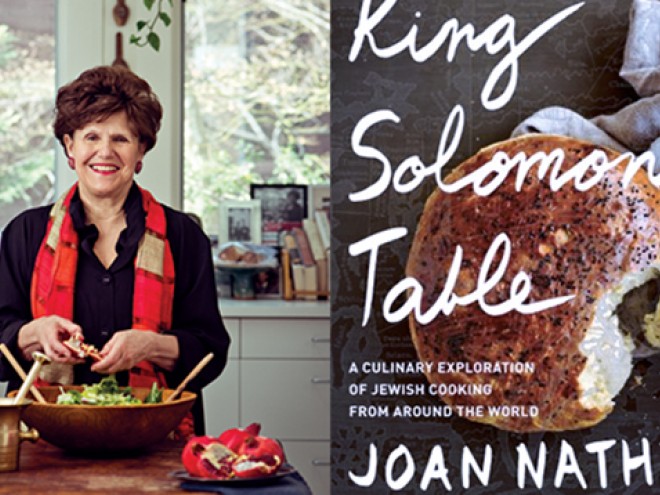

Food, family, and memories are at the heart of Joan Nathan’s warm and wide-ranging memoir, written shortly after the death of her husband. Nathan’s memories begin with the chicken soup and al dente matzo balls served in her childhood home every Friday night and continue with meals in Morocco, Vietnam, Israel, Ethiopia, and the many other places her travels have taken her, shaping her life and career.

All four of Nathan’s grandparents were born in Eastern Europe, in different areas, and came to the United States under different circumstances at different times. But whatever the differences in their backgrounds, they continued to gather their family around the table for holiday celebrations, sharing their various traditions. For the Sabbath, they served many of the dishes that the generations before them had served. Nathan’s father, who came to the United States from Germany around 1929, favored German dishes like sauerbraten and sweet and sour carp. Her mother’s family had immigrated earlier and were “American”; her mother often cooked from The Settlement Cookbook and updated traditional dishes a bit, much as Nathan has done with her own recipes.

Nathan grew up in comfortable homes in Larchmont, New York, and Providence, Rhode Island. Her first trip abroad was to France the summer she was seventeen. She returned for a junior year abroad in college — a formative time, and her first real introduction to French culture and cuisine. Even in Paris, Shabbat dinner with a French family was much the same as it was at home, underscoring for Nathan the wonder of the Jewish religion.

After college, Nathan settled for a few years in New York. She cooked the recipes featured in The New York Times, wrote for a food magazine, explored ethnic restaurants, and met people who have remained friends over the years. But at twenty-six, in pursuit of an interesting life, she took a brief trip to Israel and was captivated. She returned some months later to study Hebrew. A reporter for Haaretz steered her to Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek’s office for a job, and she was hired as the foreign press attaché, escorting distinguished guests around the city.

Two events in Jerusalem changed Nathan’s life: she briefly met Allan Gerson, the man she would later marry after reconnecting with him at home, and, as a letter to her parents put it, she decided to write “a future bestseller.” She and Judy Stacey Goldman, a colleague, invited members of the foreign press to cooking lessons in the kitchens of women from the many communities in Jerusalem. By watching them, Nathan learned to cook, and she still learns recipes with their owners standing beside her. She and Goldman wrote down the women’s stories along with their recipes, setting the format for Nathan’s cookbooks.

Nathan met Allan Gerson again in 1972, and they began dating right away. She was comfortable with him; he was unafraid of strong women, and throughout their long and happy marriage, he supported her career at the same time that he pursued his own active and challenging career. After their marriage, Gerson’s work brought them to Boston, where Nathan’s career as a food writer took shape under the tutelage of The Boston Globe’s food critic. When Gerson’s career moved them to Washington, which became their permanent home, the Globe’s food critic sent a letter to The Washington Post’s food coeditors, who agreed that Nathan could publish articles whenever a good subject came to her — a flexible arrangement that allowed her to work at home while raising three children.

Nathan’s and Gerson’s careers introduced them to a host of interesting and prominent people, and their gift for family and friendship brought many of them into their lives, often at table over good food. Among the many meals she recalls was the Gerson family seder, a solemn event conducted in fluent Yiddish and Hebrew. It was a contrast to her family’s more modern seders — led in hesitant English by her German-born father, with dry kosher Cabernet instead of Manischewitz — as well as her own elaborately planned seders with many guests, led by Gerson. Shabbat dinners, often with friends, were a special event in their family’s week. On trips, Nathan and Gerson often had casual lunches with leading chefs, food writers, home cooks, and government figures, greatly enriching Nathan’s life and career. These chance meetings opened doors for her both professionally and intellectually.

The book is organized around Nathan’s memories, brief chapters accompanied by more than a hundred recipes. Brief excerpts from letters to her parents and her diaries offer a glimpse into Nathan’s personal life, which has been marked by the sadness of losing twins at their birth and the unexpected and devastating death of her husband.

Israel has never left Nathan; there she learned much about herself as a Jew and the role food plays in our lives and our history. It has spurred her to research and preserve traditional foods, particularly Jewish foods, that define us and our cultures, in order to pass them on to the next generation. This book shines with love — love for family, for tradition, and for the meals that bring us together.

Maron L. Waxman, retired editorial director, special projects, at the American Museum of Natural History, was also an editorial director at HarperCollins and Book-of-the-Month Club.