Aharon Shabtai’s Requiem is dominated by a single long poem that explores the poet’s childhood and youth in Tel Aviv, reconstructing the texture of mid-century life even as it mourns its irrecoverable loss. This title poem unfolds through street names, neighborhoods, domestic interiors and specific people — the ordinary geography of a childhood rendered with almost documentary precision.

Shabtai regards the figures who populate his memories as “the living dead” — neither fully present nor entirely absent, existing only in language and recollection. This framing transforms the poem beyond personal nostalgia into a requiem for a vanished world. The Tel Aviv of Shabtai’s youth has been displaced by conflict and historical rupture.

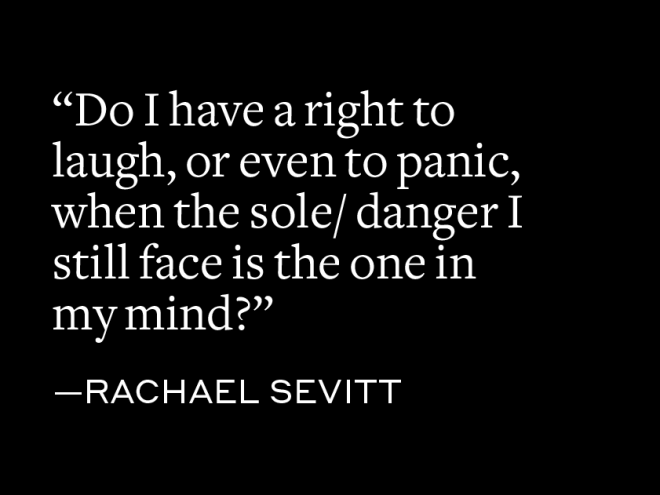

This collection offers something more elusive than the political poems for which Shabtai is known: a sustained and measured lament for what has been lost. The poem “Requiem” becomes an act of both resurrection and burial, summoning a vanished world through staccato language that is simultaneously intimate and encompassing. Images accrue in terse lines: children throwing water bombs from a roof at the corner of Frishman and Dizengoff, armored cars parked nearby. Children play; military machinery waits. These moments capture a world overshadowed by violence, yet Shabtai renders them with such understatement that the devastation arrives quietly, accumulating through detail rather than declaration. Even domestic violence is stripped to its essential horror. The narrator describes the sound of his father’s belt on “Aharon’s backside” and then interjects: “Come and see:/Father is/

made of air,/and even the chair/and the blows are abstract … ”.

Peter Cole, a distinguished poet and translator deeply versed in both biblical and modern Hebrew, is well-attuned to Shabtai’s poetic tone, its rhythms and depth of feeling. This is the third book he has translated by Shabtai and arguably the most important. In his erudite introduction, Cole reflects on finding both “sentence” and “solace” in Requiem. The “sentence” lies in Shabtai’s insistence that readers confront reality, their own as well, no matter how uncomfortable; the “solace” emerges from poetry’s capacity to bear witness unflinchingly, to insist on attending to what lies beyond.

In “Tikkun,” a poem written three days after the October 7 massacre, as Israel began bombing Gaza while preparing its troops for invasion, there is a sense of fatality, regret, and great compassion: “Only wisdom of the heart could mend it/only the surgeon, the doctor,/the good teacher, the teachers/the medic — an Arab, a Jew — /only the quiet traveler/riding a bicycle …”. This catalog of ordinary grace — the medic, the teacher, the traveler on a bicycle — offers small gestures of humanity against burgeoning destruction. Requiem offers a different perspective not just on the conflict but also on the world we live in today. The collection stands as both elegy and testament, both gentle and devastating.

Joanna Chen is a British-born writer and literary translator from Hebrew to English whose translations include Agi Mishol’s Less Like a Dove, Yonatan Berg’s Frayed Light (finalist for the National Jewish Book Awards), and Meir Shalev’s My Wild Garden. Her own poetry and writing has appeared in Poet Lore, Mantis, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Narratively, and the Washington Monthly, among other publications. She teaches literary translation at the Helicon School of Poetry in Tel Aviv.