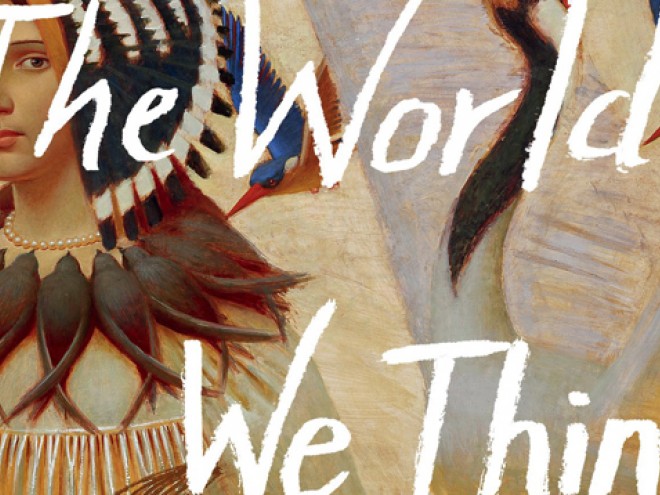

In her debut collection of short stories, Dalia Rosenfeld displays a refreshing way with the raw stuff of life, taking special delight in awkward encounters, mismatched pairings, uncertain destinies, and sexy indeterminacies.

The Worlds We Think We Know contains stories that touch both the heart and mind and Rosenfeld is a skilled alchemist who does not particularly care to answer every question readers might have about her restless, maladapted, or otherwise unsatisfied characters but instead rewards us with deep and sometimes startling glimpses into the mysteries of love and human connections of all kinds. As the title itself hints, Rosenfeld’s stories move fluidly across time and borders yet each delves into the familiar, intimate spaces of difficult, sometimes wounding relationships between lovers, spouses, parents, and children. And her sophisticated mastery of a range of tonal registers, styles, and voices ensures that each of these poetically fragmented stories feels fresh and distinct. And happily that range often proffers deft touches of levity, as when the protagonist of “Flight” sardonically declares, “I threw my arms out in the most Jewish way I knew how, which is to say not at all, having grown up in Indiana.” Or when one narrator foreshadows the likelihood of a disastrous outcome of a double date set in an Indian restaurant when she casually observes that the two couples sit “within arm’s length of a statue of Kama, the Indian love god who was burned to ashes after trying to rouse the passion of the greater god Shiva.” And here is the beleaguered narrator of “Invasions”: “It was a bad habit of my mother’s to always send me old Yiddish novels in translation. She thought that if I spent enough time back in the shtetl, I would stop complaining about my life in Ohio and realize that scouring the Food Lion for organic broccoli was nothing compared to the forced conscription of ten-year-old Jewish boys into the tsarist army.”

As that moment of rueful self-awareness suggests, Rosenfeld’s characters can find themselves unmoored or caught up in pasts that stubbornly make claims on the present. In “The Next Vilonsky” an old man’s errand to the corner makolet (grocery) in Tel Aviv turns into an epic odyssey into introspective memories. Elsewhere, Rosenfeld veers into decidedly stranger realms such as in “Swan Street,” where an invisible wife abandoned in Eastern Europe haunts her husband’s every step in America. In the aftermath of a brutal mugging, the professor of “Bargabourg Remembers” struggles to commit every visceral detail of the incident to memory but instead finds himself in thrall to the phantom of a lost love. As soon as I finished it, I found myself rereading “Floating On Water” with great pleasure. It’s a deeply knowing, sensual, and often very funny paean to female friendships, without a false note of sentimentality, that interweaves love along with the petty jealousies and exasperating demands that are somehow inevitably part of the fabric of even the most sustaining relationships.

The Shoah quietly intrudes into some of these empathic, risk-taking stories in the kind of small yet indelible ways that deliver more profoundly unsettling psychological insights than they might otherwise in the hands of a less subtle writer. And though many of Rosenfeld’s beleaguered characters are quite verbose, she is equally skilled at handling the kinds of silences that take us deeper into her characters’ self-awareness and also their capacity for compassionate understanding of others (even when it is at the distance of some decades), such as the narrator of “Liliana, Years Later,” who recollects her childhood piano teacher: “Liliana never spoke of her broken heart, just as I do not speak of mine now, because when one tries to put pain into words, the words themselves become agents of new pain, like fresh paper cuts, and cannot be used again.”

Rosenfeld, a graduate of the Iowa Writers Workshop who currently lives in Tel Aviv, proves a reliably mordant observer of imperfect and vulnerable characters struggling with unfulfilled appetites and desires, in language that consistently dazzles. Even the shorter works have lingering power, conjuring up richly immersive places inflected by whimsy and perhaps a touch of the uncanny, and are occasionally heartbreaking. In a few stories they seem to hint at more than one reality. She displays a keen awareness of loneliness as the essential human condition, yet grace notes of humor inflect even her more melancholy stories. There are moments when her portrayals of the foibles of misfits and unreliable narrators or cryptic urban encounters are appealingly suggestive of a Raymond Carver or Grace Paley sensibility (their quiet epiphanies, little notes of grace), but mostly Rosenfeld is unlike any writer you’ve ever read and I can’t wait to see what she does next.

Ranen Omer-Sherman is the JHFE Endowed Chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Louisville, author of several books and editor of Amos Oz: The Legacy of a Writer in Israel and Beyond.