Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

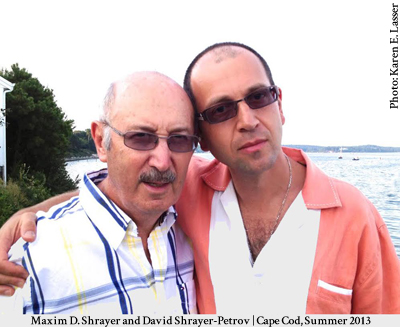

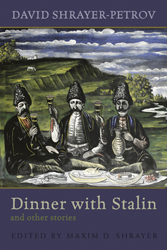

This week father and son, neighbors in Brookline, Massachusetts and longtime collaborators, David Shrayer-Petrov and Maxim D. Shrayer discuss Dinner with Stalin and Other Stories in a three-part conversation conducted for the Visiting Scribe series. They will be blogging here for the Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning all week.

Maxim D. Shrayer: Papa, let’s start with a basic question. What are the stories gathered in Dinner with Stalin about?

Maxim D. Shrayer: Papa, let’s start with a basic question. What are the stories gathered in Dinner with Stalin about?

David Shrayer-Petrov: Above all else, Dinner with Stalin is about Russian Jews who found themselves abroad, first emigrating and later grafting themselves onto American soil. My characters perceive themselves, especially when overseas, as Americans — even though at home in the US they may think of themselves as Russians. But if you pressed them on the subject, “You’re Russian?” they would answer, “Yes, we’re Russian. Russian Jews.” As a writer I weave the fabric of my stories from different balls of yarn: my characters appear as Americans at work, as Russians at home, while in fact they have Jewish souls.

MDS: If we take the title story, “Dinner with Stalin,” as a symbol of the whole collection, how does it express the essence of your book?

DSP: The title story doesn’t only encapsulate the Jewish question. This group of émigré friends is visited by Stalin who has come from the other world. It’s actually an actor who masterfully plays Stalin, bringing the whole thing to the point of absurdity; the audience begins to believe him — the way they temporarily believe the actor playing Hitler in Ray Bradbury’s “Darling Adolf.” Present among this motley group are representatives of a number of nationalities of the former USSR, including Armenians, Azeris, Ukrainians, Russians, and Jews. Here Jews enjoy parity, and the émigré protagonist and his wife, Mira, end up asking Stalin the most blunt questions about Soviet and Jewish history.

MDS: So in fact “Dinner with Stalin” is a fictional model of the former Soviet Union?

DSP: …yes, that’s right. And also a model of a United Nations session…

MDS: …convening in post-Soviet times…

DSP: …exactly. At this session representatives of different post-Soviet nations testify about Stalinism and other harrowing aspects of the past.

MDS: Let’s digress for a moment and talk about your path as both a writer of fiction and a Jewish author. You started out as a poet, and you hadn’t become a writer of stories until the 1980s, having already written three novels and two books of non-fiction. The short story became one of your chosen forms. Why do you think you embraced the short story later in your career?

DSP: I believe this had to do with what I demanded of myself. I had been regarding the short story as a gem that not every writer gets to cut and polish. For me the stories of Zweig, Thomas Mann, Bunin, Nabokov— Chekhov above all — and of the early Soviet writers such as Olesha and Babel—represented the highest mastery of the craft. As a younger writer I had stories to tell, but I hadn’t fathomed how to compose short stories until I became a Jewish refusenik and was living in isolation from the official Soviet culture. And already as a refusenik I understood that there is a magic device of fiction-making, which one needs to realize in order to compose a story — to conjure it up rather than copy it from so-called real life. This magic fictional quality — an inimitable vibration of feeling — is something Chekhov’s stories exhibit in the fullest sense.

MDS: You had a very early piece of short prose titled “The Sun Fell into the Mine Shaft” from the early 1960s, which was about a young Jew’s realization that he could never be fully integrated into the Russian mainstream. I find it very intriguing that you hadn’t begun to write short stories until you became a refusenik.

DSP: The Jewish question had been a source of much trepidation. As you can imagine, by the early 1960s, I had already lived through a lot. The Doctors’ Plot [of 1952 – 1953], when Jews had again experienced a nearing abyss, occurred during my senior year in high school. The Jewish theme had stung me. But before we applied for exit visas, I had been distancing myself from writing fiction about Jews. I had been tying my own Jewish hands. But I couldn’t suppress these urges.

MDS: Your stories, almost all of them, feature Jewish characters. Is writing almost exclusively about Jewish characters what makes a writer-Jew a Jewish writer?

DSP: I think that’s important. At least there’s a Jewish calculus at work. If you’re a writer of Jewish origin but you never write about Jews… hmm…I don’t know.

MDS: And if this is not only a matter of Jewish themes or characters but something else, can one then speak of a Jewish poetics — or specifically of the Jewish short story? What is that Jewish something else in writing?

DSP: It’s a secret, and I don’t think you can isolate it the way scientists isolate a gene. Otherwise one could take this Jewish something and transfer it onto any material. Luckily, it doesn’t work this way. Each writer has his or her own Jewish secret. Babel has his own, and we immediately feel it. Or take Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov and their classic novels The Twelve Chairs and The Golden Calf. Even though most of the characters aren’t Jewish, the authorial grin is very Jewish. Or consider Grossman’s Life and Fate… the way the author mourns the Jewish fate as he sets it against the backdrop of the entire country’s devastating fate.

MDS: Yes, but I think that in Grossman there’s also a distinctly Jewish intellectual commentary. I was actually wondering: To what extent is a Jewish writer a child of Judaic civilization and to what extent is he a product of his own epoch and language?

DSP: I’m not a great fan of the notion of genetic Jewish memory. There are universal human genes, and there are genes highly prevalent in the Jewish genotype, but I don’t think this has much to do with Jewish writing. What does matter is that writers grew up in a Jewish family — even in post-revolutionary Russia — where they were exposed to Jewish conversations.

Check back tomorrow for Part 2: “A Jewish-Russian Writer as New Englander”

Born in Leningrad in 1936, David Shrayer-Petrov emigrated to the United States in 1987. He is the author of twenty-three books in his native Russian and of several books in English translation, including Jonah and Sarah: Jewish Stories of Russia and America and Autumn in Yalta: A Novel and Three Stories. His latest book is the collection Dinner with Stalin and Other Stories. Dinner with Stalin was edited by the author’s son, Maxim D. Shrayer, a writer and a professor at Boston College. Two stories in the collection were translated by Emilia Shrayer, Shrayer-Petrov’s wife of over fifty years and a former refusenik activist. The other translators include Arna Bronstein and Aleksandra Fleszar, Molly Godwin-Jones, Leon Kogan, Margarit Ordukhanyan, and Maxim D. Shrayer.

Copyright © 2014 by David Shrayer-Petrov and Maxim D. Shrayer

Related Content

Maxim D. Shrayer is a bilingual writer and a professor at Boston College. Born in Moscow in 1967 in the family of the writer David Shrayer-Petrov, Shrayer emigrated to the United States in 1987. He has authored over ten books in English and Russian, among them the memoir Waiting for America: A Story of Emigration, the story collection Yom Kippur in Amsterdam, and the Holocaust study I SAW IT. Shrayer’s Anthology of Jewish-Russian Literature won a 2007 National Jewish Book Award, and in 2012 he received a Guggenheim Fellowship. Shrayer’s latest book is Leaving Russia: A Jewish Story, a finalist for the 2013 National Jewish Book Awards. A recent review in Jewish Book World called Leaving Russia a “stunning memoir” and recommended that it “should be assigned reading for anyone interested in the Jewish experience of the twentieth century.” Read additional blog posts he’s written for the Visiting Scribe here.