Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

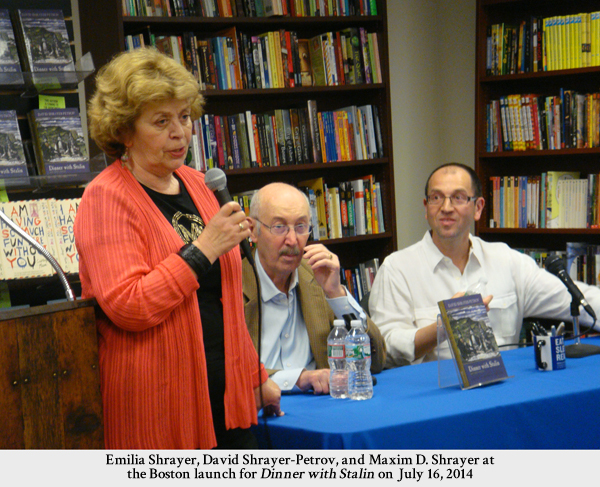

This week father and son, neighbors in Brookline, Massachusetts and longtime collaborators, David Shrayer-Petrov and Maxim D. Shrayer discuss Dinner with Stalin and Other Stories in a three-part conversation conducted for the Visiting Scribes series. Read the first installment, “A Fictional Model of the Former USSR,” here. They will be blogging here for the Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning all week.

Maxim D. Shrayer: Papa, let’s continue with our topic. What happens after a Jewish writer emigrates from the USSR to the USA? Of the fourteen stories in Dinner with Stalin, you wrote 13 in America, as an immigrant. What has changed in your creative laboratory?

Maxim D. Shrayer: Papa, let’s continue with our topic. What happens after a Jewish writer emigrates from the USSR to the USA? Of the fourteen stories in Dinner with Stalin, you wrote 13 in America, as an immigrant. What has changed in your creative laboratory?

David Shrayer-Petrov: First of all both the immediate environment and the greater environment have changed. Most of these stories fashion Russian—Jewish-Russian—characters living in America. In this sense, I’ve become an American writer. Take the story “The Valley of Hinnom.” Even though much of the action is set in Moscow and in Israel, I could never have written this story without knowing that the main characters are former refuseniks living in the US.

MDS: One more “American” question, then. A number of your stories are set in New England cities and towns, in Rhode Island and Massachusetts — Providence, Little Compton, Worcester, towns on Cape Cod. And there are also European stories set in Paris, Moscow and Leningrad, and scenes of Rome and Jerusalem, composed, as it were, from memory. How have many years of living in New England influenced your stories?

DSP: I’ve lived here for almost twenty-eight years. I think that I’ve rooted myself in New England. It has become my second — now my main — habitat. If asked about it, I now respond without hesitation that I’m a New Englander, even though I lived for fifty years in Russia, in Leningrad and Moscow. I actually wonder how I was able to write, so many years later, the short story “The Bicycle Race” and set it in the Leningrad of my youth. I guess I really wanted to fish out of the depth of memory and to reconstruct the image of a very complex individual. He’s called “Shvarts” in my story, but his prototype was Eduard Chernoshvarts (nicknamed “Chyorny” which literally means “black” in Russian), a famous Soviet cyclist. He was a Jew who had risen above the masses in the 1940s, when there was a strong popular anti-Jewish sentiment. In my story he’s a great Jewish athlete, but hardly a Jew of high moral standing…

MDS: …yes and no, but to return to the question of a Jewish writer in New England… if we look analytically at your stories, it appears that you write without estrangement about today’s life in New England (as in such stories as “A Storefront Window of Miracle”) and about your youth in Russia (as in “Mimosa Flowers for Grandmother’s Grave”). Yet you write with a much greater degree of estrangement about your last three Soviet decades, especially the refusenik years.

DSP: Yes, I think it’s true. In this regard “Mimosa Flowers for Grandmother’s Grave,” the only story in Dinner with Stalin that I wrote while still living in Russia, is a case in point.

MDS: Our English translation of this story had first appeared in Commentary, and I think it tapped our shared memory of a Jewish past in Eastern Europe. A Jewish family forever broken by turbulent events, a halutz, love and longing — these are things to which Jewish-American readers might be particularly attuned.

DSP: I think that throughout his or her entire life, every Jew is haunted by some poignant detail of the past… Say, one had a great-grandmother who was a traditional Jew in the full sense of this term. And then, across countries and languages, this image of a Jewish great-grandmother was being passed on from immigrant grandmother to mother to American child. And it has thus survived.

MDS: I agree, “Mimosa Flowers for Grandmother’s Grave” is the most universally Jewish story in Dinner with Stalin. So let’s continue with questions of Jewish family and marriage. In each of your stories you observe and comment on aspects of love and marriage between Jews and non-Jews. Critics have pointed out that for you as a Jewish storyteller this is a key question. Why?

DSP: I have observed very many mixed marriages growing up. My uncle, my mother’s brother, was married to a Russian woman who was an observant Orthodox Christian. And there’s a family legend that when I was an infant, a five- or six-month old, she brought me to church. But who can now tell…. The very marriage between Russia and Jewry is, I think, a symbol that was supposed to divert the striking hand of antisemites — and at times it did do that, but at other times it did not, only nurturing false hopes.

MDS: This is a very relevant topic in today’s America, and for that reason I think the stories in Dinner with Stalin will be of interest to Jewish-American readers.

DSP: Yes, but here there’s a religious agenda to this problem as one must decide about the religion of one’s children. In the Soviet Union such decision-making was less manifest in mixed marriages. But in 1953, Stalin’s last year and the pivotal year for Soviet Jews, with genocidal scenarios in the air, there were non-Jewish spouses who, out of fear, sought to dissolve their marriages to Jews. This shameful conduct of some of the non-Jews married to Jews resembles what happened in Germany after the Nazis came to power.

MDS: Before we pause and have some tea with lemon, let me ask you what is now a fashionable question: What’s your list of 5 Jewish books which everyone must read — that is, besides Dinner with Stalin?

DSP: This is a very partial list. I would recommend: The Ugly Duchess by Feuchtwanger, Heavy Sand by Rybakov, Shosha by Bashevis Singer, Ravelstein by Bellow (and given Thomas Mann’s Jewish connections, Death in Venice), and Ilf and Petrov’s dilogy The Twelve Chairs and The Golden Calf.

MDS: May I also add a personal favorite — and may this wish soon come true— your refusenik saga Herbert and Nelly, which is being translated into English.

Check back tomorrow for Part 3: “Crypto-Jews and Autobiographical Animals”

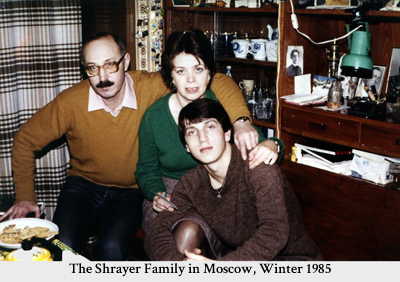

Born in Leningrad in 1936, David Shrayer-Petrov emigrated to the United States in 1987. He is the author of twenty-three books in his native Russian and of several books in English translation, including Jonah and Sarah: Jewish Stories of Russia and America and Autumn in Yalta: A Novel and Three Stories. His latest book is the collection Dinner with Stalin and Other Stories. Dinner with Stalin was edited by the author’s son, Maxim D. Shrayer, a writer and a professor at Boston College. Two stories in the collection were translated by Emilia Shrayer, Shrayer-Petrov’s wife of over fifty years and a former refusenik activist. The other translators include Arna Bronstein and Aleksandra Fleszar, Molly Godwin-Jones, Leon Kogan, Margarit Ordukhanyan, and Maxim D. Shrayer.

Copyright © 2014 by David Shrayer-Petrov and Maxim D. Shrayer

Related Content

Maxim D. Shrayer is a bilingual writer and a professor at Boston College. Born in Moscow in 1967 in the family of the writer David Shrayer-Petrov, Shrayer emigrated to the United States in 1987. He has authored over ten books in English and Russian, among them the memoir Waiting for America: A Story of Emigration, the story collection Yom Kippur in Amsterdam, and the Holocaust study I SAW IT. Shrayer’s Anthology of Jewish-Russian Literature won a 2007 National Jewish Book Award, and in 2012 he received a Guggenheim Fellowship. Shrayer’s latest book is Leaving Russia: A Jewish Story, a finalist for the 2013 National Jewish Book Awards. A recent review in Jewish Book World called Leaving Russia a “stunning memoir” and recommended that it “should be assigned reading for anyone interested in the Jewish experience of the twentieth century.” Read additional blog posts he’s written for the Visiting Scribe here.