Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

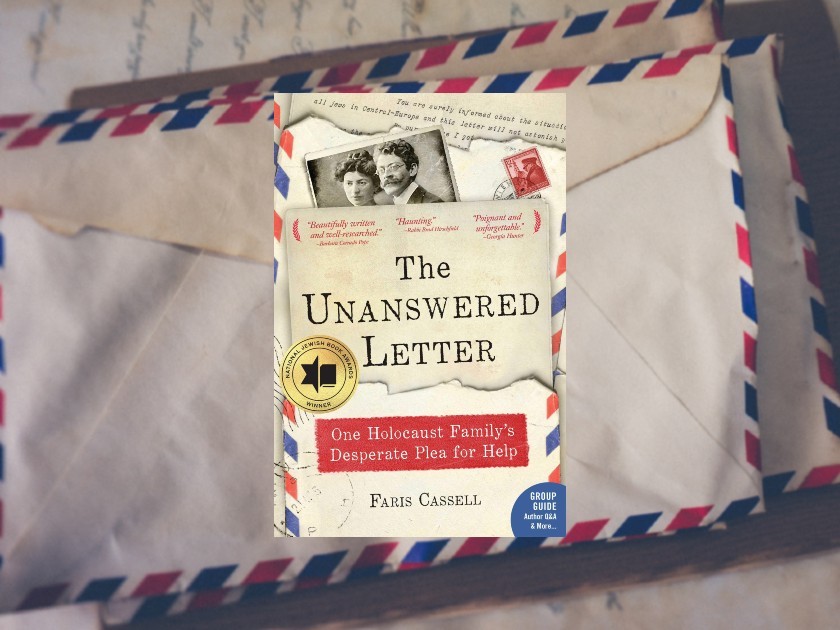

Writing is a journey of discovery. This was made clear to me when I came across one fragile piece of paper — a frantic sixty-year-old letter — that held more questions than answers. On my journey, I encountered people, places, events, and emotions that filled the pages of my book with life. But as the story took twists and turns, some information inevitably fell by the wayside. Those experiences — those facts — made their presence felt, shadows hovering over the story. They formed a backstory that enhanced the book but didn’t intrude. I’d like to share several of those side stories that were crucial to my research, along with being compelling, important, and inspiring.

Hilde Geissen

Hilde Geissen, survivor of four years in Terezin Concentration Camp, breathed life into my book with her meticulous translation of over a hundred letters written by a desperate Viennese Jewish family, struggling from 1938 to 1942 to escape Nazi terror. I was researching my book about the Berger family when I discovered a cache of letters between family members, written in German but in an archaic form of handwriting that hadn’t been in use for sixty years.

I struggled to find a way to have them translated. Professional translators charged more than I could afford. At that time, I happened to interview Hilde, and mentioned that I was searching for a translator. I saw her blue eyes sparkle, a grin spreading across her face. I hesitated, but blurted out, “Would you be interested?” Before I could finish the sentence, she interrupted. “Sure. I’d be glad to do it.”

And so began my year or more of weekly Wednesday visits to Hilde’s living room, where she sight-read those faded brittle sheets, the blurred ink wrapping around corners, up along edges of the thin airmail paper. I sat facing her, typing on my laptop as she read. Sometimes she pulled out a magnifying glass, struggling to decipher the faded ink. Other times, she sailed through the pages, stopping only to clarify colloquial phrases for me, or to share stories of her own harrowing imprisonment.

She’d survived brutality, disease, freezing temperatures, hunger, and fear of what the next day would bring — and yet, Hilde was one of the most generous, cheerful, and lively people I’ve ever known. From this diminutive stalwart woman, who stood just under five feet tall, I learned about courage and determination, and witnessed her unquenchable zest for life. She passed away in 2017. I miss her still.

The American Bergers, Clarence Berger’s Helmet

The American Bergers: Clarence Berger’s Helmet

The central tragedy of my book comes from a desperate 1939 letter from a Viennese Jewish man, Alfred Berger, begging for immigration help from strangers with the same last name in America. “Help us,” he pleaded, “it is our last and only hope.”

Those strangers, Clarence and Bea Berger, did not respond to the letter. When I interviewed their descendants, I struggled to bridge that span of time and understand who Clarence and Bea were and what had motivated them. Why save that letter, reminding them of what they had not done?

I learned that Clarence had been raised dirt poor, farming in Bakersfield, California, then served briefly in France the U.S. Army at the end of World War I. Just across the border, earlier, Corporal Adolf Hitler was gassed in a ferocious battle with the British.

At war’s end, Corporal Berger returned to America, no longer as young and naïve, but still optimistic and enterprising. He moved to Los Angeles, married Bea, a Canadian immigrant, and opened a car repair business, the Ten Grand Garage, at the corner of Tenth and Grand streets. His business thrived until the Great Depression. He rented out parking spaces on the site and learned to weld, holding on to his business as the economy seesawed through the 1930s, unemployment sometimes hitting nearly 20 percent.

As his home in downtown Los Angeles lost value, he and Bea, a homemaker, moved to a modest home near San Diego, carefully including Alfred Berger’s letter with their family papers and World War I army artifacts. I began to see how this self-made, resilient blue-collar worker may have felt buffeted by world events and strove to stay ahead of trouble.

I developed empathy for Clarence and Bea, and still remind myself to refrain from judging them for not answering that desperate plea for help. The letter had moved them enough that they saved it over the course of three decades, a death, and two moves. In their position, what would I have done with Alfred Berger’s letter?

Leo’s Painting. Martha’s Music.

Alfred and Hedwig Berger had built a good, lower-middle class life in Vienna before the German occupation. Through my research I followed their family’s rise from the 1800s, when Alfred’s hardworking father had traveled the Austrian Empire peddling household goods, sometimes carrying a pack on his back. Alfred became a wholesale textile merchant, and moved from the poor Jewish neighborhood of his youth, across the Danube to a hardworking blue-collar area of Vienna near the vibrant cultural city center.

Alfred and Hedwig especially loved Vienna’s music. Although not able to afford many extras in their lives, they managed to purchase tickets to the concerts nearby. As their family grew, they took their daughters. By the time of the German occupation, their oldest daughter, Martha, had become a concert-level pianist, their youngest daughter a confident, thriving teenager. Martha married a resourceful wholesale salesman of leather goods, Leo, who was also a talented artist.

All that progress, and more, was swept away by the Nazis. Martha and Leo managed to escape to America, where Martha taught piano lessons and Leo worked in a factory, painting when he found time. When I traveled to Vienna with Martha Berger’s daughter, Celia, to research the family’s story, we visited the famous Musikverein concert hall where Martha once performed. I could only vaguely appreciate what Celia felt, but her face seemed transported with joy, and I felt privileged to be a part of that moment of her reclaiming her family’s history. Celia recently sent me one of her father’s paintings, which our family treasures.

These are just a few of the people who made a lasting impact on me during my writing journey. Without them, the story could not have been told. They have touched many people, and they keep the Bergers’ story in my heart.

Passionate about history, this is Faris’ second Holocaust book. The first won the 2020 National Jewish Book Award/Holocaust and 2020 American Society of Journalists and Authors Award/History. She lives with her husband in Eugene, Oregon.