Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

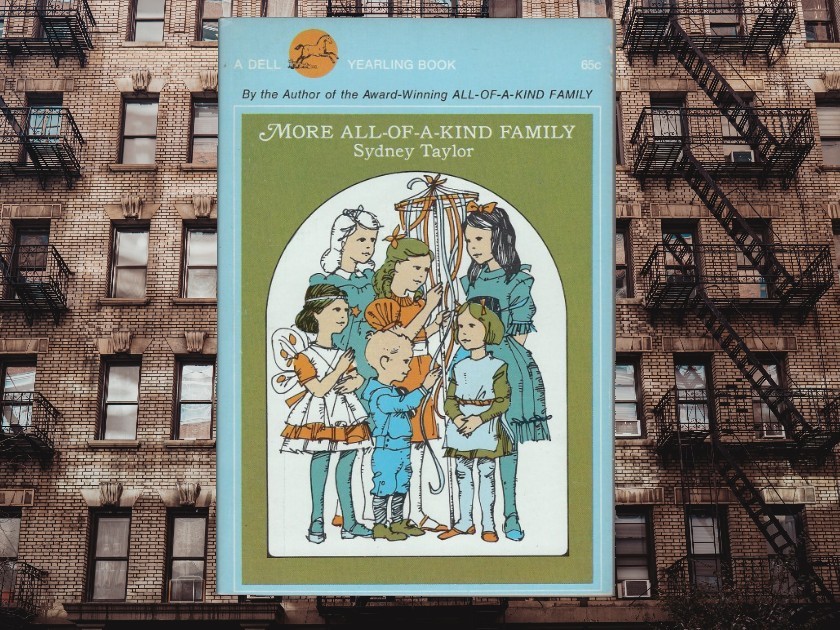

More All-of-a-Kind Family, by Sydney Taylor

Summer has historically been a time of both leisure and peril for children, and the same is true in the world of children’s literature. Frightened at the possibility of exposure to dangerous diseases, parents were often forced to balance physical health and emotional wellbeing when caring for their children. Although many people may have had the privilege of prioritizing freedom of action over fear of disease, that is no longer true in our times. Wearing masks and social distancing today echo the same anxieties of earlier eras, when diseases with no cure and no means of prevention were rampant. In Sydney Taylor’s More All-of-a-Kind Family (1954), the looming threat was polio, a terrifying plague which seemed to strike at random but usually targeted the young. Those who survived were often left with permanent physical disabilities, as well as emotional scars. Crowded urban communities were usually seen as a higher risk zone, but no one was safe. In today’s discussions about the need for more diverse representation in Jewish-themed children’s books, people with disabilities are assumed to have been invisible in books of the past, yet there are notable exceptions.

In Taylor’s story of Jewish life on the Lower East Side of New York in the early twentieth century, the author confronts disease and its multi-faceted consequences with sensitivity and realism, encouraging discussion within the framework of Jewish values. Jewish tradition has many reminders of the value of human life and of the obligation to judge people not by their external appearance but by their inner qualities. As the Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) teaches, “Do not look at the container, but at that which is in it.” Yet the reality of coping with changes wrought on the human body by disease is not resolved easily, even within a supportive Jewish community.

In the chapter entitled “Epidemic in the City,” Taylor describes the sense of foreboding in 1916, when an epidemic struck New York, killing more than two thousand people and disabling many more. Parents resorted to whatever resources gave them some confidence — not masks or hand sanitizer — but prayer, small bags of camphor placed around children’s necks, and, if at all possible, a trip to the country. Taylor intones ominously, “Soon there were empty seats in the classrooms, and the clang of an ambulance bell was heard more and more frequently.” The fear of contagious disease was never far away in the era before vaccines or antibiotics; in the first book of the series, scarlet fever (strep infection) forces the family to quarantine during Passover. Yet the polio virus raised the specter of both mortality and disability on a large scale.

When polio strikes the family, it is not the children, but their Uncle Hyman’s fiancée, Lena, who is its unexpected victim; just as today, when data about COVID-19 points to age and underlying medical and socioeconomic conditions as risk factors, when individuals outside of those higher risk groups become ill people can be shock as well. The family is incredulous: “’Lena, a grown woman! How is it possible?’ Mama asked, ‘Infantile paralysis is a children’s disease!’” Although the book takes place prior to World War I, Taylor (1904−1978) was an adult during the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had contracted the disease as a healthy thirty-nine-year-old. Although an unwritten agreement with photographers meant that most Americans were not aware of the full extent of his disability, they knew that his experience was atypical and, therefore, even more frightening.

Jewish tradition has many reminders of the value of human life and of the obligation to judge people not by their external appearance but by their inner qualities.

Soon, the family’s life is destabilized by grief and insecurity. The coming simcha of a wedding is replaced by Uncle Hyman’s sadness and fear: “Like a wandering ghost, he plodded back and forth from the hospital to the house, his face pale, his hair all matted on his forehead, and his eyes red-rimmed.” Finally, Mama and Uncle Hyman come home with — considering worse possible outcomes — good news. Lena will indeed recover, although she has lost the use of her left leg. Given the possible effects of the disease, this prognosis is deemed lucky. The effects of illness on the family spread out in unpredictable ways, bringing anger, resentment, and frustration, as well as loss. Lena calls off the engagement, convinced that Hyman will now only marry her out of pity, and be burdened for the rest of his life at a time when the idea of accommodations for those with disabilities were far in the future.

Even before Lena becomes ill, her courtship with Uncle Hyman has been fraught with tension. Hyman is, even in the affectionate view of Mama — his sister — a schlumper, physically unkempt and socially awkward. He washes loudly at the kitchen sink, “grunting and sputtering all the while.” His childlike enjoyment of food is less than elegant, and he seems completely unaware of ordinary manners. Yet Hyman is kind and affectionate, offering exactly the kind of example which the Pirkei Avot suggests in cautioning Jews to evaluate people according to their souls, not their outfits. He first meets Lena at his sister’s home; “Lena the Greena” is a “greenhorn,” a recent immigrant to America, who has lost her family in Europe and is working in a factory to support herself. In spite of her poverty and her imperfect English, Lena is fastidious and polite, careful of social norms, and eager to assimilate into her new country. While they would seem to be something of an odd couple, Hyman falls in love with her, unconcerned with her status as a poor orphan.

When Hyman shows up late to escort her to the Second Avenue (Yiddish) theater, unshaven and wearing dirty clothes, she is furious. All her pent-up anger at the compromises she has made seems to erupt as she accuses Hyman of disrespecting her: “For you it’s all right to take a girl to the theater looking like a schlepper so everybody should talk…I thought you were beginning to be different – to take care a little of yourself. But I made a big mistake. Once a schlepper, always a schlepper!” Hyman’s confusion at her reaction is genuine; he might well be quoting the rabbinic source when he responds to her: “So you see me in my working clothes. Is that so terrible? After all, people should like each other for themselves and not — ” Only to have Lena accuse him of believing that “people should go around looking like pigs,” a strong comparison for an observant Jew. After his sister and nieces convince him to get cleaned up and try again, he and Lena become engaged.

When Lena sustains her disability, her relationship with Hyman is completely altered — at least from her perspective. While before she had tolerated his lack of external beauty, now she is sure that he will never be able to tolerate her altered physical appearance. In addition, she has become depressed, her mind as affected by trauma as her body. Mary Stevens’ black and white line drawing depicts the young woman as prematurely aged, with deep wrinkles and unkempt hair. Previously so fastidious, she sits by the window with a shawl carelessly safety-pinned around her shoulders. Hyman embodies the Jewish principle of acceptance and understanding of human dignity. He has already assured Mama that Lena’s disability is irrelevant to him: “Who’s pitying her? So she won’t be able to run and jump around! What do I care?…All I know is I love her, and I want her to be my wife.”

When Lena sustains her disability, her relationship with Hyman is completely altered — at least from her perspective.

During their trip to Far Rockaway to remove the children from the epidemic and to aid in Lena’s recovery, Mama finally shocks Lena back into reality, pointing out that she has allowed her feelings of loss to consume her, completely ignoring her former fiancé’s own sense of loss and his unconditional love for her. Mama’s approach may seem harsh by contemporary standards; today, validating Lena’s sense of loss would seem more compassionate. Her plea may seem sentimental, but it reflects Jewish values and Hyman’s deep and uncompromising love: “Don’t you know Hyman would rather have you with a bad leg than anyone else in the whole world?” Lena admits that she still loves Hyman and will marry him. Their relationship will have a new basis of equality, each seeing the other as the person within, not just the “container.”

Hyman and Lena’s wedding is a contrast of external appearances and inner realities. Hyman’s elegant starched shirt is uncomfortably restrictive, but he understands that it is a temporary acknowledgement of a special day: “It’s a good thing I don’t have to be dressed like this every day,” he comments. The guests relish the exaggerated elegance of the wedding hall, an important indicator for immigrants and new Americans that they have succeeded, at least for a day. “Artificial flowers…worn red plush seats,” and a mirror with “a large irregular crack running down the center,” seem almost comical examples of luxury. While appearances may be ultimately less important in Jewish tradition, they do have a role, particularly in the Jewish ideal of hiddur mitzvah, beautifying a religious obligation to emphasize its importance. Lena’s bout with polio will not exclude her from this experience. When she begins to walk towards the huppah (marriage canopy), the reality of her disability reasserts itself: “Slowly, haltingly, she began the long walk. The guests looked on sympathetically as, somewhat clumsily, she dragged her lame leg. But Lena was unaware of anyone. Her head was high and proud.” Guests signal to the musicians to slow their pace and they do so.

Lena and Hyman in Sydney Taylor’s More All-of-a-Kind Family are forced to negotiate a new relationship in the aftermath of her illness.

When an epidemic strikes, human vulnerability becomes acutely obvious. Lena and Hyman in Sydney Taylor’s More All-of-a-Kind Family are forced to negotiate a new relationship in the aftermath of her illness. Taylor looks at individuals in one community and analyzes how their personalities and interpersonal conflicts interact with normative Jewish values, enabling them to move forward in their lives. Lena will never be exactly the same, but her ultimate worth is unchanged, according to the precept of Pirkei Avot, “Do not despise any man, and do not discriminate against anything, for there is no man who has not his hour, and there is no thing that has not its place.” Contemporary Jewish-themed books for children can continue to offer greater inclusion of people with disabilities. Taylor’s fiction, through carefully drawn characters and skillful narrative, offers a reminder that some older works do reflect this fundamental Jewish value, in a way which young readers will never forget.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.